Just in case it wasn’t clear, Emomali Rahmon is likely to be named the Leader of the Nation.

Just in case it wasn’t clear, Emomali Rahmon is likely to be named the Leader of the Nation.

Political process

Caught between superpowers Russia and China, can Central Asia's "stans" exert their independence amid a changing energy landscape?

Caught between superpowers Russia and China, can Central Asia's "stans" exert their independence amid a changing energy landscape?

In Kazakhstan, it seems, there are second chances for daughters tainted by political scandal.

In Kazakhstan, it seems, there are second chances for daughters tainted by political scandal.

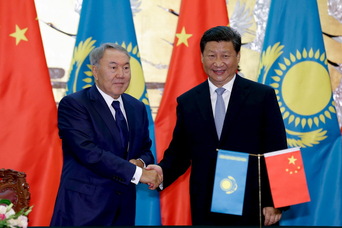

The Kazakh government has a delicate balancing act between Russia and China, according to an opinion article by David Clark in The New Statesman, Britain’s weekly current affairs magazine, on August 4.

The Kazakh government has a delicate balancing act between Russia and China, according to an opinion article by David Clark in The New Statesman, Britain’s weekly current affairs magazine, on August 4.

CIS states, such as Russia and Kazakhstan, have sought to manipulate the extradition process in order to persecute opponents, write Ben Keith and Rebecca Niblock.

CIS states, such as Russia and Kazakhstan, have sought to manipulate the extradition process in order to persecute opponents, write Ben Keith and Rebecca Niblock.

The government of Kazakhstan tries to use a U.S. federal statute to take down an opposition newspaper. Central Asia may be one of the least economically integrated regions extant, but the countries remain as tapped into Western legal structures as any – especially when attempting to smother opposition voices. The latest bit of legal manipulation came last year, when the Kazakhstani government used the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), a U.S. federal statute, to sue unnamed “Doe” defendants in federal court in New York.

The government of Kazakhstan tries to use a U.S. federal statute to take down an opposition newspaper. Central Asia may be one of the least economically integrated regions extant, but the countries remain as tapped into Western legal structures as any – especially when attempting to smother opposition voices. The latest bit of legal manipulation came last year, when the Kazakhstani government used the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), a U.S. federal statute, to sue unnamed “Doe” defendants in federal court in New York.

Small and medium-size states such as Kazakhstan survive and do well when, like good surfers, they learn to ride and take advantage of new geopolitical waves. Conversely, they fail when they ignore them. Kazakhstan now has a new opportunity. Sweeping across Central Asia is the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative launched by China’s President Xi Jinping. The origins of this initiative are complex. It could be an effort to counterbalance the clear dominance of the United States in the maritime sphere. It could also be an effort to revive Central Asia’s key role in world history.

Small and medium-size states such as Kazakhstan survive and do well when, like good surfers, they learn to ride and take advantage of new geopolitical waves. Conversely, they fail when they ignore them. Kazakhstan now has a new opportunity. Sweeping across Central Asia is the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative launched by China’s President Xi Jinping. The origins of this initiative are complex. It could be an effort to counterbalance the clear dominance of the United States in the maritime sphere. It could also be an effort to revive Central Asia’s key role in world history.

Since 2013, the nuclear energy arm of the Russian state has controlled 20 percent of America's uranium production capacity. Rosatom's acquisition of Toronto-based miner Uranium One Inc. made the Russian agency, which also builds nuclear weapons, one the world's top five producers of the radioactive metal and gave it ownership of a mine in Wyoming.

Since 2013, the nuclear energy arm of the Russian state has controlled 20 percent of America's uranium production capacity. Rosatom's acquisition of Toronto-based miner Uranium One Inc. made the Russian agency, which also builds nuclear weapons, one the world's top five producers of the radioactive metal and gave it ownership of a mine in Wyoming.

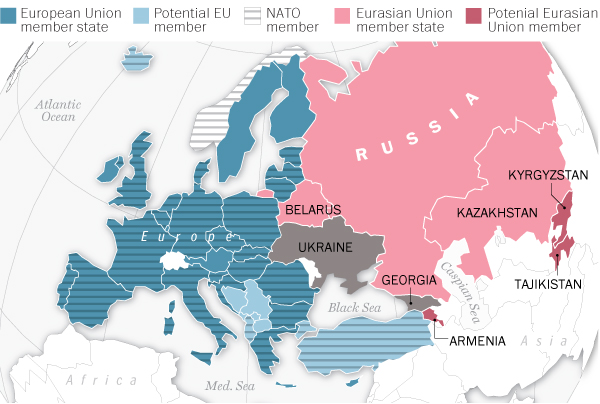

For most former Soviet states, the consensus about Russia's overtures in Crimea is very simple: It's bad. Georgia, itself on the receiving end of Russia's military in 2008, isn't too pleased, with President Giorgi Margvelashvili saying Moscow's moves "represent flagrant interference in the internal affairs of the sovereign state [...] and pose a threat to Ukraine's territorial integrity." Estonia's Foreign Ministry said that Russia's actions threatened the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of Ukraine, while representatives of Lithuania and Latvia have also spoke out to criticize Moscow.

For most former Soviet states, the consensus about Russia's overtures in Crimea is very simple: It's bad. Georgia, itself on the receiving end of Russia's military in 2008, isn't too pleased, with President Giorgi Margvelashvili saying Moscow's moves "represent flagrant interference in the internal affairs of the sovereign state [...] and pose a threat to Ukraine's territorial integrity." Estonia's Foreign Ministry said that Russia's actions threatened the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of Ukraine, while representatives of Lithuania and Latvia have also spoke out to criticize Moscow.

The Soviet Union collapsed more than 20 years ago, yet genuine democracy is still a stranger in most of the 15 former republics. Ukraine, where at least 25 people were killed on Tuesday, is just the latest bloody example. From President Vladimir Putin's hard-line rule in Russia to the 20-year reign of Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus to the assorted strongmen of Central Asia, many post-Soviet rulers consistently display a fondness for the old days, when opposition was something to be squashed, not tolerated.

The Soviet Union collapsed more than 20 years ago, yet genuine democracy is still a stranger in most of the 15 former republics. Ukraine, where at least 25 people were killed on Tuesday, is just the latest bloody example. From President Vladimir Putin's hard-line rule in Russia to the 20-year reign of Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus to the assorted strongmen of Central Asia, many post-Soviet rulers consistently display a fondness for the old days, when opposition was something to be squashed, not tolerated.

Subcategories

How a Chinese company exports the Great Firewall to autocratic regimes

More details

Kazakhstan diverting crude to Russia’s CPC as Azerbaijan deals with tainted oil

More details