For most former Soviet states, the consensus about Russia's overtures in Crimea is very simple: It's bad. Georgia, itself on the receiving end of Russia's military in 2008, isn't too pleased, with President Giorgi Margvelashvili saying Moscow's moves "represent flagrant interference in the internal affairs of the sovereign state [...] and pose a threat to Ukraine's territorial integrity." Estonia's Foreign Ministry said that Russia's actions threatened the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of Ukraine, while representatives of Lithuania and Latvia have also spoke out to criticize Moscow.

For most former Soviet states, the consensus about Russia's overtures in Crimea is very simple: It's bad. Georgia, itself on the receiving end of Russia's military in 2008, isn't too pleased, with President Giorgi Margvelashvili saying Moscow's moves "represent flagrant interference in the internal affairs of the sovereign state [...] and pose a threat to Ukraine's territorial integrity." Estonia's Foreign Ministry said that Russia's actions threatened the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of Ukraine, while representatives of Lithuania and Latvia have also spoke out to criticize Moscow.

There are, however, two states where the reactions are far more complex, and far more interesting: Kazakhstan and Belarus. On Monday, Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev was said to "understand" Russia's position, according to Reuters, which struck many as a very carefully worded way of phrasing it. While Belarus has been relatively quiet on the issue, it has apparently recognized the new, post-Maidan government in Kiev, an unusual break with Moscow.

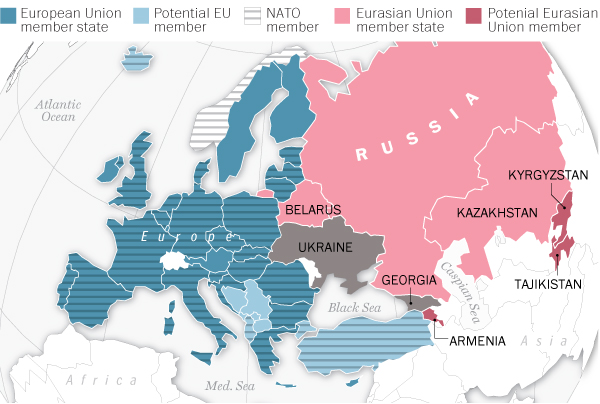

What explains these cautious, mixed messages? Well, it's simple: Kazakhstan and Belarus are the two other states currently signed up to join Russia's "Eurasian Union": Their very future is tied to the Russian plan that has been referred to by virtually every publication as President Vladimir Putin's "dream" of a continent-spanning alliance that would rival Europe and the United States.

It's an ambitious dream, certainly, designed not only as an economic alternative to the European Union, but also as a philosophical mission to make Russia and its neighbors the center of their own geopolitical landscape (for a great history of the ideas behind it, check over at the Boston Globe).

So far, Belarus and Kazakhstan are members of the Customs Union, an economic bloc formed in 2010 as a precursor to the Eurasian Economic Union, which will itself be formed in 2015. Armenia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are also expected to one day become members, and Russia long had hopes that Ukraine and even Georgia might join.

Russia's actions in Crimea, however, are sure to make both Kazakhstan and Belarus worried. "It's this whole issue of Russian speakers," Fiona Hill, director of the Center on the United States and Europe at the Brookings Institution, says in an e-mail. "In each case they've got something to be concerned about."

The Kremlin has justified the use of force in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine with a vow to protect ethnic Russians, an excuse that's easily applied in other places. In Kazakhstan, there's a significant minority of ethnic Russians in the north of the country, Hill points out – some 24 percent of the country is said to be ethnically Russian, and the language is widely spoken. While Belarus has fewer ethnic Russians (8.3 percent), it has largely become a Russophone state and there are a lot of murky questions about who might succeed Alexandr Lukashenko. Of course, Russia has agreed to respect the sovereignty of both countries, but they did that with Ukraine, too: The 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which Russia says they are ignoring due to the change in government in Ukraine. Neither Kazakhstan nor Belarus has recognized South Ossetia and Abkhazia, the states that broke away from Georgia, by the way.

"Kazakhstan's Nursultan Nazarbayev has traditionally sought to maintain constructive relations with both Russia and West, but if a Cold War redux erupts over inclusion of Crimea into Russia, Astana might be forced to take sides and therefore lose the opportunity to play great powers off each other," Simon Saradzhyan, a research fellow at Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University, explains in an e-mail. "The same goes for Belarus' Alexandr Lukashenko, who tends to make overtures to the West whenever he wants a major concession from Russia." U.S. or European Union sanctions against Russia would hurt both countries, Saradzhyan notes, as they are now tied economically to Moscow.

Putin perhaps knows that Crimea represents a threat to his Eurasian "dream." On March 5, he called a summit in Moscow with Kazakhstan's Nazarbayev and Belarus' Lukashenko, which struck Joanna Lillis of Eurasia Net "as more propagandistic than substantive" – a chance to shore up support before May 1, when a pact due to formally create the "Eurasian Economic Union" is due to be signed.

The irony here, of course, is that the Euromaidan protests began when Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych turned away from potential E.U. membership toward more economic cooperation with Russia, and, it was presumed, eventual membership in the Eurasian Union. As Yanukovych was forced from Kiev and a pro-Western government installed, that became less and less likely, and Russia turned its attention to Crimea. Russia's foreign policy message subtly changed: From one of a supranational union and cooperation to Russian domination. Kazakhstan and Belarus can't fail to notice that. Whether they have any better option right now, however, is harder to say.

Adam Taylor writes about foreign affairs for the Washington Post. Originally from London, he studied at the University of Manchester and Columbia University. You can follow him on Twitter here.