Post-independence Kazakhstan has seen a revival in Kazakh genealogies, sub-ethnic lineages and identities.

Post-independence Kazakhstan has seen a revival in Kazakh genealogies, sub-ethnic lineages and identities.

The Adai Ata mausoleum. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.As the sun sets on Mangystau, in Western Kazakhstan, hundreds of people ascend to the top of Otpan Tau, the region's highest spot. Above them, the golden-domed mausoleum of Adai Ata, the semi-mythical ancestor of the local clan, the Adai. The electric lights of a museum and temporary yurt encampment stand against the darkness below. People enter inside the mausoleum’s tallest tower and perform a blessing to the spirit of the ancestor, who rests in a large sarcophagus decorated with ornaments and the Adai’s arrow-shaped emblem. Then, they gather around a large metal torch by a totemic statue of a wolf. Once the organisers and the distinguished guests arrive, the torch is lit amid solemn calls for Kazakh unity. The moment is evocative, both austere and joyful. For the last ten years it has been part of Amal Kuni, a lesser known spring New Year celebrated in the western part of Kazakhstan.

Post-independence Kazakhstan has seen a revival in Kazakh genealogies, sub-ethnic lineages and identities, whose knowledge has become increasingly relevant for personal identification, social belonging, and nation-building, touching even the region’s oil industry. Tens of hagiographic volumes have been recently published to commemorate the pioneers of Mangystau’s oil industry, portraying them as role models for the younger generations and establishing a genealogical tradition for the sector. The publisher, Munaishy Fund, was founded by Nasibkali Marabayev, a veteran oilman who strongly advocated for the construction of the Otpan Tau complex. Since the 2000s, the celebration of industry and clan genealogies have become intertwined.

The Adai are the largest ru, or clan, within the “younger” of the three tribal confederations (zhuz) that make up the Kazakh nation. According to Sabyr Adai, a renowned aqyn (“poet-improviser”) and the man considered the initiator of the festival, the Adai have a special place and mission within the Kazakh nation.

“Adai Ata was the youngest heir of the three hordes. That’s why his descendants are considered to be the owners of karashanyrak, the paternal home, where the duties of the whole nation, its treasured culture, traditions, dreams and wishes are protected and preserved from generation to generation since time immemorial. The youngest son who inherits the karashanyrak is responsible for the continuation and the transmission of the whole spiritual heritage,” Adai told the author.

The karashanyrak is the central tent-shaped building. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

The karashanyrak is the central tent-shaped building. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

The celebration of Amal Kuni is one of these traditions, despite having returned to public life only recently. In contrast to the Persian New Year of Nowruz, widely celebrated in Central Asia, it occurs a week before the spring equinox and is construed as a distinctively ethno-national festivity. Its origins date back to the times of nomadic pastoralism, when clans would meet and greet each other after winter, before leaving for the summer pastures. Amal Kuni honours the renovation of life and the beginning of a new cycle. This year the celebrations resonated with the “spiritual renovation” programme launched in 2017 by President Nursultan Nazarbayev as part of the wider Modernization 3.0 policy. Echoing the previous Kazakhstan 2030 and Kazakhstan 2050 strategies of political and economic development, the current campaign makes explicit reference to the modernisation of national identity through the selective preservation of “those aspects which give us confidence in the future,” while dropping those “that hold us back.”

Bringing the periphery at the centre of renovation

The name Adai has a connotation of fierce, war-like attitude, given the clan’s centuries-long resistance to colonial encounters with the Tsarist Empire first, and then Soviet collectivisation and sedentarisation campaigns in the 1930s, when the local population was decimated by famine and out migration. The Adai’s reputation has endured through the 1989 nationalist unrest, which resulted in the mass deportation of North Caucasian nationals from the region, and the tragic shootings of striking oil workers by security services in Zhanaozen in 2011.

Amal Kuni and the setting of its celebration aim to dispel the Adai’s negative depiction through performances and narratives. Fierceness is turned into a positive expression of pride, while enmity is transformed into an effort to promote ethno-national unity in the face of perceived threats of cultural annihilation and social disintegration. As one of the region’s elders put it on the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the complex last year: “I would come to Otpan Tau in the old days too, but it was impossible to go up to the top. Only God knows how we managed to go up. That was the time of the slavery to communism. And now we are facing the catastrophe called globalism. Sabyr (Adai) and Svetkali (Nurzhanov, another renowned aqyn) are among the ones who are fighting against it.”

People in front of the karashanyrak. March 2018. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

People in front of the karashanyrak. March 2018. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

Similar to previous state-led modernisation projects, “spiritual renovation” leaves room for local interpretations and implementation. In Otpan Tau, the rejection of these “alien and endangering” cultural and political models is coupled with the active construction of a neo-traditional identity. In this context, Adai Ata performs the role of spiritual guide and embodies the shared belonging to the community. Worshipping and paying tribute to the spirit of the ancestor provides the Adai – self-defined as the principal guardians of traditional values – with the confidence to stand up to the uncertainties of what Nazarbayev has called “the beginning of a new, largely unclear, historical cycle.”

The local intelligentsia constantly spells out the fear that external contamination would cause the ethnic extermination of the Kazakhs, constructing the Adai as core models for the political, cultural, and moral body of the nation. “Whilst Kazakhs in the north are mixed with Russians and in the south with Uzbeks, Adai always kept their blood pure,” a participant at Amal Kuni declared, stressing the importance of ethnic purity and the practices that guard and reproduce it.

At a round table during the celebrations, local historian Otynshy Koshbaiuly reassessed a largely imaginary geographical isolation as evidence of cultural purity (which ironically mirrors Tsarist-era orientalist depictions of Mangystau as a remote, untouched land). The intelligentsia gathered in the museum’s conference room agreed: Otpan Tau is the place from which the country’s cultural and spiritual renovation is spreading, “enlightening” the Kazakhs in re-discovering their authentic national self. At the round table, mainly composed of elder men, representatives of other regions’ cultural centres regarded Mangystau and the Otpan Tau complex as having healing properties. One participants quipped that, if going to the country's culturally polluted north “makes one's heart ache,” coming here “lifts the spirit.” In today’s world, then, the defence and propagation of Kazakhness are framed as urgent needs, responding to the threat globalisation poses to “fragile” traditional social relations, gender norms and political allegiances.

As Sabyr Adai, the initiator of the festival, wrote in a local newspaper in 2004, “the unity of Kazakhs cannot artificially disregard the role of the ru and the zhuz (tribal confederation), (but) it starts with understanding one’s place and preserving the established order. The political virus and ʻinter-genocidalʼ slogan ʻLove everyone by forgetting your own father – this is a sign of patriotism!ʼ has entered the national consciousness, pushing young people towards democratic rootlessness. Under the conditions of globalisation, we need to renovate our saints, historical figures, traditions and customs, ethno-cultural heritage and folklore.” In the same column, Adai called for the erection of the mausoleum and the establishment of the cultural-historical complex at Otpan Tau.

Participants descend after the lighting of the fire. March 2018. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

Participants descend after the lighting of the fire. March 2018. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

This discourse of patriotism and external threat is embodied by the ritual fire (ot) and its annual lightning. As the philologist Islam Zhemenei put it, the fire “enlightens” the viewer about one’s own history and traditions. But it also alerts and communicates the presence of an enemy. Its present significance is given historical roots by tracing the practice back to pre-Soviet times, when, according to folklore, the approaching of Turkmen knights would be detected and signalled from the peak of Otpan Tau.

After the fire has been lit on the top of Otpan Tau, people start descending the steps to the museum below, passing through two rows of young men, dressed as Turkic warriors and holding plastic torches. One of the organisers whispered in their ears: “Make them feel as if they were the akim,” (head of the local administration). So they straighten up and fix their gazes as in the performance of a military exercise, recognising the solemn atmosphere of the moment.

Renovating the corporate spirit

In front of the karashanyrak, people move from one yurt to another to share food and tea, and greet each other for the New Year. Actors perform on stage the coming of spring on a white horse. Just steps away, men watch other men competing in weightlifting, arm and horseback wrestling. Women wear colourful traditional dresses and state officials show off their suits, while numerous participants are in their working uniforms, representing a constellation of companies of the local oil industry. During competitions, contenders are called by their names and company affiliation, while company buses crowd the parking lot.

Although Amal Kuni and the cultural centre have been supported by local and national authorities, private individuals and local oil companies have contributed significant resources. Indeed, some people complain that, since Amal Kuni is not sanctioned as a national holiday, they cannot attend the public celebrations, reducing it to a holiday for oilmen off from rotation and their families.

Mangystau is Kazakhstan’s second-largest oil producing region and a historical base for the national oil company Kazmunaigas. In contrast to the more recently developed oil and gas fields of Tengiz, Kashagan, and Karachaganak, which are owned and operated by transnational consortiums in segregated extraction enclaves, the older oilfields in Mangystau are much more embedded within the surrounding social environment.

Oil workers in their uniforms wait before a tournament of horse-back wrestling. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

Oil workers in their uniforms wait before a tournament of horse-back wrestling. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

The oil companies in Mangystau, such as OzenMunaiGaz (OMG) and MangystauMunaiGaz (MMG), have taken a role in establishing local and national traditions and figures. For instance, in 2009 MMG financed the construction of a mausoleum dedicated to the legendary heroine Kalamkas within the premises of an oilfield named after her. OMG is currently engaged in researching the life of Orazgambet Turmagambetov, a little known local figure executed during the 1930s repression and now presented as the very first Kazakh geologist. Companies also run beauty contests in national costumes for women, sport competitions for men, and tour expeditions around the region to explore one’s own national identity, camping in the enchanting landscape of the region. OMG has also financed the Otpan Tau complex, offered gifts for its staff and prizes for the winners of sport competitions, and supplied the complex with fresh water.

Companies rarely consider such initiatives as part of their corporate social responsibility, but frame their involvement as their national duty, even though their language often echoes globalised corporate practices. All these activities, an insider told the author, forge the company's “corporate spirit”, which is paramount in curbing possible worker strikes through the affective power of patriotism and national culture.

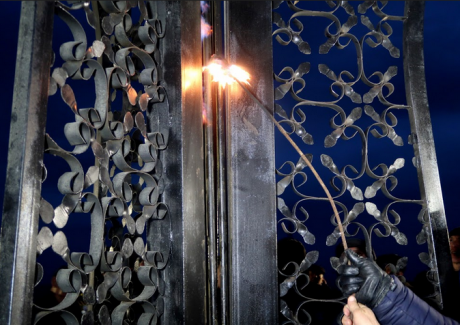

The gasoline-soaked rod lights the torch. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

The gasoline-soaked rod lights the torch. March 2017. Photo courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.

Sitting in a yurt in Otpan Tau, an enthusiastic participant said that “by participating in events such as Amal Kuni, workers are ‘renovating’ their attitudes towards management, leaving behind the direct confrontations which have characterised the recent past,” expressing how the intelligentsia’s nationalist and corporatist discourse resonates with the oil companies’ industrial relations strategy.

Last year, chilly winds were blowing during the ceremony of fire. Although a large group of attendees encircled and protected the organiser from the violent gusts, he remained helpless. After a few unsuccessful attempts to ignite the flame, someone dunked a rod into the fuel tank of a nearby car. The gasoline-soaked rod approached the ritual torch: the flame was finally lit.

This article benefited from significant research assistance by Laura Berdikhojayeva.

OpenDemocracy, 8 May 2018