For years, journalists — and reportedly even federal investigators — have pored over U.S. President Donald Trump’s business deals for signs that criminals and their dirty money may have entered his orbit.

For years, journalists — and reportedly even federal investigators — have pored over U.S. President Donald Trump’s business deals for signs that criminals and their dirty money may have entered his orbit.

Donald Trump, Tevfik Arif, and Felix Sater attend the Trump SoHo launch party in September 2007 in New York. Credit: Mark von Holden / WireImage]Donald Trump, Tevfik Arif, and Felix Sater attend the Trump SoHo launch party in September 2007 in New York. Credit: Mark von Holden / WireImage

The Trump SoHo tower in New York has been one of Trump’s most scrutinized developments. Among other controversies, it has been alleged in court that three condominiums in the building were purchased using funds linked to a massive fraud case in the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan.

Now, a new investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and the Dutch television program Zembla sheds new light on the case.

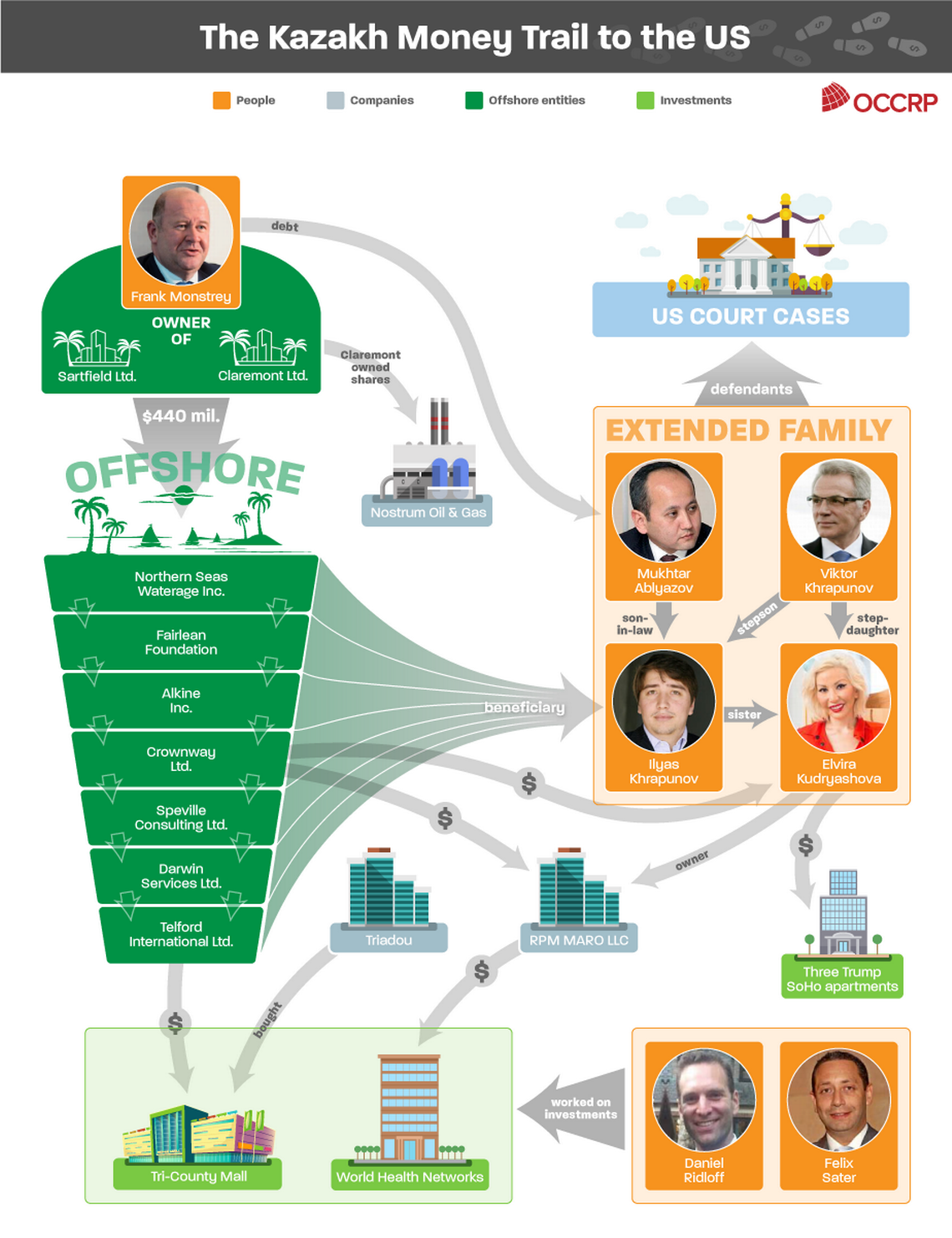

Using documents never before made public, it reveals exactly how the three million dollars used to purchase the condos found their way to New York. It also appears to support allegations raised in court that the money may be of criminal origin.

Over US$ 30 million from the same tainted source was used to finance other investments in the United States with the help of Felix Sater, a convicted financial fraudster and one-time Trump advisor. Sater’s former company, Bayrock Group, partnered with Trump to build the troubled Trump SoHo.

The documents and interviews provide a detailed account of the money’s winding global trail — via offshore shell companies and a bank linked to terrorism financing — into the United States.

Its origin can be traced to a single stash of roughly $440 million connected to a notorious fraud case involving Kazakhstani billionaire Mukhtar Ablyazov. Last year, the fugitive banker was sentenced in absentia to 20 years in prison by a Kazakh court on charges that included embezzling billions of dollars from the country’s BTA Bank, which he formerly headed.

If the money is indeed Ablyazov’s, the real estate investments could put those involved, including Sater, in legal jeopardy.

Although not conclusive, the complex offshore trail used to move the money shows “classic red flags for money laundering,” said Richard K. Gordon, the head of the anti-money laundering graduate program at Case Western Reserve University Law School in Cleveland, Ohio.

“If the ultimate source of the money was criminal proceeds, then that makes it a money laundering case,” Gordon said.

That raises a risk, albeit small, of legal trouble for Sater and others linked to the deals, Gordon said. Although the legal bar for prosecution is high, a case could be made against anyone who knowingly conspired to launder the money, or had it end up in their accounts.

Kazakh oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov arrives at a courthouse in Lyon in October 2014 before a hearing as part of his appeal trial regarding his extradition to Russia. Credit: AFP / Philippe MerleKazakh oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov arrives at a courthouse in Lyon in October 2014 before a hearing as part of his appeal trial regarding his extradition to Russia. Credit: AFP / Philippe Merle

Kazakh oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov arrives at a courthouse in Lyon in October 2014 before a hearing as part of his appeal trial regarding his extradition to Russia. Credit: AFP / Philippe MerleKazakh oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov arrives at a courthouse in Lyon in October 2014 before a hearing as part of his appeal trial regarding his extradition to Russia. Credit: AFP / Philippe Merle

Family Ties

The latest revelations appear to prove accusations against Ablyazov and other wealthy Kazakhstanis in two drawn-out civil court cases in New York and California.

The cases — brought by Kazakhstan’s biggest city, Almaty, and BTA Bank — allege that Ablyazov and his relative by marriage, former Almaty mayor Viktor Khrapunov, made investments in real estate and businesses in the United States using stolen money.

Khrapunov, whose stepson, Ilyas, is married to Ablyazov’s daughter, lives in exile. He and his family stand accused of stealing approximately $300 million through corrupt land deals during his time as mayor.

Ilyas and his sister, Elvira Kudryashova, are also defendants in the case.

Lawyers for the accused have denied that the money came from illicit sources, arguing that the financing for the investments had come from another relative by marriage.

Documents filed in court show that, between 2012 and 2014, Ilyas and Elvira were helped with their U.S. investments by Felix Sater, the former Trump advisor, and another former Trump Organization employee, Daniel Ridloff.

The investments include the $1.2 million purchase of a former facility for the mentally disabled in Syracuse, New York, and the purchase of shares in a health kiosk company.

The largest investment facilitated by the two men was the 2013 purchase, for roughly $30 million, of the debt on the Tri-County mall in the suburbs of Cincinnati. They sold their interest in the property for $45 million three months later.

The relationship with the Kazakhstanis appears to have been very profitable for at least one of the two Americans.

A legal dispute saw Sater withhold the Ohio mall sale money from the Khrapunovs. The impasse was only resolved after the Khrapunov firm behind the investment agreed to let him walk away with the majority of the proceeds, according to a document filed by plaintiffs in the New York case in December.

Just why Sater managed to make tens of millions of dollars from the deal is unknown, but the document provides a hint.

According to the document, Sater was granted the settlement after his lawyer sent a letter to a Khrapunov company in October 2013 stating that Ilyas had told him that “that the funds for several of [Khrapunov’s] companies belonged to Mr. Ablyazov.”

The existence of this letter raises the possibility that Sater was fully aware he was helping invest money linked to Ablyazov’s ongoing criminal fraud case.

The Khrapunovs also made other investments worth tens of millions of dollars with no apparent help from Sater and Ridloff. Those deals included Los Angeles property and two hotel and condominium developments in New York.

The 46-story Trump SoHo hotel and condominium tower was developed in part by Sater’s former company, Bayrock, and opened in 2010.

The tower soon proved to be a disappointment, plagued by vacancies. Two of Trump’s children, Donald Jr. and Ivanka, reportedly narrowly avoided prosecution after allegations were raised that they tried to boost condominium sales in the building by lying to prospective investors.

The Trump Organization withdrew from the troubled project in 2017 following a slew of negative publicity. The development is reported to be among the business deals being looked into by special counsel Robert Mueller.

The firm behind the tower also has links to the Khrapunovs, showing that Sater has known the family for at least a decade. In 2007, as the Trump SoHo was in development, the family set up a Dutch joint venture with Sater’s Bayrock, called KazBay, aimed at coal mining and power generation in Kazakhstan. Bayrock and the Khrapunovs also partnered on a condominium project in Switzerland the following year.

The Dominick, the Manhattan high-rise known as the Trump SoHo until 2017. Credit: ZemblaThe Dominick, the Manhattan high-rise known as the Trump SoHo until 2017. Credit: Zembla

Elvis Has Bought the Building

Documents presented in court show that much of the money for the U.S. investments came from offshore, largely from accounts at FBME Bank, a now-defunct Tanzania-based financial institution with offices in Russia and Cyprus. The bank was sanctioned by the U.S. government in early 2016 after it was found to be involved in money laundering, terrorism financing, and arms proliferation.

But the exact money trail, and how it connects with Ablyazov’s world, has so far been hidden from public view. The investigation by OCCRP and partners, however, shows for the first time that the money can be traced back to hundreds of millions connected to Ablyazov’s fraud case.

The revelations come from a set of documents first unearthed in the United Kingdom, which has been the center of the protracted global wrangle over the Kazakhstani mogul’s assets.

In 2016, a lawyer for BTA Bank — the Kazakhstani bank defrauded by Ablyazov — disclosed to a U.K. court that a private investigator had approached the bank with what he said was evidence that a Dubai-based offshore financial planner named Eesh Aggarwal had been building and running a network of offshore companies that were laundering the stolen money.

According to the lawyer, the private investigator presented documents taken by what he claimed were “Israeli computer hackers” from Aggarwal’s computer. They revealed, he said, that Aggarwal had worked for Ablyazov’s son-in-law, Ilyas, in building and running a network of offshore companies that funneled hundreds of millions of dollars between FBME accounts.

(The private investigator, Stuart Page, did not respond to emails from a reporter seeking an interview.)

BTA’s own private investigators began following Aggarwal. In mid-June 2016, noticing that he had flown into the United Kingdom, lawyers for the bank sought — and received — an order from a British court to require him to turn over his files.

OCCRP and partners were granted access to the files in late 2017 by a source with direct knowledge of the case. They include correspondence, organizational charts, and loan and debt agreements.

The documents show that Ilyas Khrapunov — under the codename “Elvis” — was the ultimate beneficiary of a complex web of almost a dozen offshore companies and trusts administered by Aggarwal that handled close to $440 million through FBME accounts.

By analyzing documents filed in the New York and California cases, reporters were able to piece together a trail that shows this money was used in part to finance key Khrapunov investments in the United States — including the Trump SoHo apartments and the Ohio mall investment assisted by Sater and Ridloff.

Several of the emails show that Sater was involved in coordinating transfers of millions of dollars to the United States. They also show his relationship with two members of the Khrapunov family. In one email discussing a $3 million transaction, Viktor Khrapunov’s stepdaughter Elvira Kudryashova — the purchaser of the three Trump SoHo apartments — refers to Sater as “my business associate.” Other emails show Ilyas in correspondence with Sater.

Aggarwal hung up when contacted by a reporter. He did not reply to a follow-up email.

Sater did not respond to written questions sent by reporters. Ridloff declined to comment via a lawyer.

Belgian Bucks

Reporters were able to use the documents to trace the money back to its original source: A Belgian businessman who claims to have been repaying an almost half-billion dollar debt to Ablyazov at a time when the fugitive banker was under a freeze order and was frantically hiding his assets from the British courts.

That businessman was Frank Monstrey, an entrepreneur who in 2004 bought Zhaikmunai, a Kazakh oil and gas company that has since gone public in the United Kingdom under the name Nostrum Oil & Gas.

The seized documents show that the entire $440 million that financed Ilyas’ offshore network came from two companies based in British offshore havens that belonged to Monstrey, who has since found himself pulled into Ablyazov’s British case.

The documents show that the companies, called Sartfield and Claremont, paid the money over a period of nearly a year in 2011 and 2012 into Northern Seas Waterage, a Seychelles-registered firm under Ilyas’ ultimate control. Aggarwal, his financial advisor, then filtered the money through the network, some of it eventually into the United States.

Lawyers for BTA managed to convince a British court early last year to freeze Monstrey’s company’s shares in Nostrum Oil & Gas. Just a month after the freeze was granted, Monstrey resigned as Nostrum’s chairman. By the middle of the year, he had reached an out-of-court settlement with BTA to sell his shares in the company to the bank.

In written responses to questions sent by OCCRP and partners, Monstrey strongly denied acting as a front man for Ablyazov’s business interests. Instead, when asked about the nearly $440 million, Monstrey said it was the repayment of a loan he had taken out years before from a Kazakhstani business partner. The debt had then been taken over by Ablyazov after the partner’s death.

In written responses to questions sent by OCCRP and partners, Monstrey strongly denied acting as a front man for Ablyazov’s business interests. Instead, when asked about the nearly $440 million, Monstrey said it was the repayment of a loan he had taken out years before from a Kazakhstani business partner. The debt had then been taken over by Ablyazov after the partner’s death.

“I have never been a proxy for or agent of Ablyazov or those I now know to have been associated with him,” Monstrey said. “I have unwittingly and innocently found myself sucked in to a battle between BTA and Ablyazov/Khrapunov.”

Monstrey declined to comment in response to detailed follow-up questions sent by reporters.

Nostrum declined a request by reporters for comment.

A spokesperson for Ablyazov, Peter Sahlas, declined to answer questions sent by reporters about the transactions and key players such as Monstrey, Sater and the Khrapunovs.

Sahlas wrote that Ablyazov was being persecuted for his opposition to Kazakhstan’s regime, and that his 2017 fraud conviction in the country could not “be considered to have the least amount of credibility given the complete lack of a legitimate legal system in this Central Asian dictatorship.”

The civil cases in the U.K. and U.S. over Ablyazov’s assets were similarly “grounded on questionable or out-of-context evidence from a corrupt country with no rule of law,” Sahlas wrote.

Ilyas Khrapunov did not respond to questions sent by reporters to a spokesman.

BTA did not respond to detailed questions sent by email.

“Catch Me If You Can”

Revelations on the money trail raise the question of whether those involved in bringing the funds to the United States violated anti-money laundering laws.

Although Sater knew the Khrapunov family for half a decade before helping in these deals, any money laundering investigation would have to find evidence he knowingly took part in a conspiracy to launder money with a criminal origin, Case Western Reserve’s Gordon said.

Meanwhile, the messy soap opera continues to wend its way through courts in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

The U.K. Supreme Court ruled in March that Ilyas Khrapunov can be pursued in that country’s courts for allegedly conspiring with Ablyazov in his attempts to conceal his assets.

In New York, too, the younger Khrapunov has run into trouble. In March, a federal judge in the district court hearing the case sanctioned Khrapunov for leaking a transcript of a deposition given by BTA’s current chief.

The judge in the case, Katharine H. Parker, was unconvinced by Khrapunov’s denials.

The judge wrote: “His tone and delivery conveyed his ‘catch me if you can’ attitude and, in this Court’s view, demonstrated his lack of credibility.”

Who’s Who?

Mukhtar Ablyazov

The former chief of Kazakhstan’s BTA Bank. He fled the country in 2009 amid a crisis that led to the bank’s nationalization, and has been accused by the bank of embezzling more than $6 billion. Ablyazov claims he is being persecuted for his opposition to the country’s ruling regime. He was convicted in absentia for the fraud in Kazakhstan in 2017. He has had more than $4.6 billion worth of judgements made against him in court in the United Kingdom, and was convicted of contempt there in 2012. Ablyazov was arrested by French police in 2013 but released three years later after a court agreed he was being sought for political reasons.

Viktor Khrapunov

The former mayor of Kazakhstan’s largest city, Almaty. Along with his wife, Leila, Khrapunov is accused of embezzling over $300 million in his time in office. Khrapunov’s stepson, Ilyas, is married to Ablyazov’s daughter, Madina Ablyazova.

Khrapunov lives in Switzerland.

Felix Sater

A Russian emigre who grew up in New York, Sater was imprisoned over a 1993 bar fight and convicted a few years later for a mafia-linked stock fraud. He avoided prison in the latter case by agreeing to become an informant for the FBI.

Sater was a co-founder of Bayrock Group, one of the developers behind the Trump SoHo tower. Trump has sought to distance himself from his former business partner, who previously carried business cards identifying himself as a “senior adviser” to the now-US president. Sater was reportedly involved in unsuccessful plans to build a Trump-branded tower in Moscow, as well as a 2017 back-channel scheme with Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, to broker a Ukraine peace deal.

Ilyas Khrapunov and Elvira Kudryashova

Ilyas Khrapunov and Elvira KudryashovaIlyas is married to Mukhtar Ablyazov’s daughter, Madina, and oversaw many of the family’s U.S. investments. Under the codename “Elvis,” he was the beneficiary of an offshore network of companies that handled the $440 million linked to Ablyazov that was used in part for these projects.

Khrapunov’s stepdaughter, Elvira, was the beneficial owner of the three apartments in the Trump SoHo developments. She was also the beneficiary of a health kiosk firm, World Health Networks, set up in the United States.

Frank Monstrey

A Belgian businessman with longstanding ties to Kazakhstan. Monstrey invested in the Kazakhstani oil company Zhaikmunai LP in 2004 and until 2017 served as its head. The company was later renamed Nostrum Oil & Gas.

Two firms owned by Monstrey were the source of the $440 million used to finance much of the U.S. investments. Monstrey denies he was a straw man hiding Ablyazov’s assets, and says the money was to repay a debt he had unwittingly come to owe Ablyazov.

Additional reporting by Chris Benevento, Lejla Sarcevic, Bermet Talant and Katarina Sabados.

Additional reporting was also provided by Kevin G. Hall and Ben Wieder of McClatchy.

WRITTEN BY AUBREY BELFORD, SANDER RIETVELD AND GABRIELLE PALUCH

OCCRP, 25 June 2018