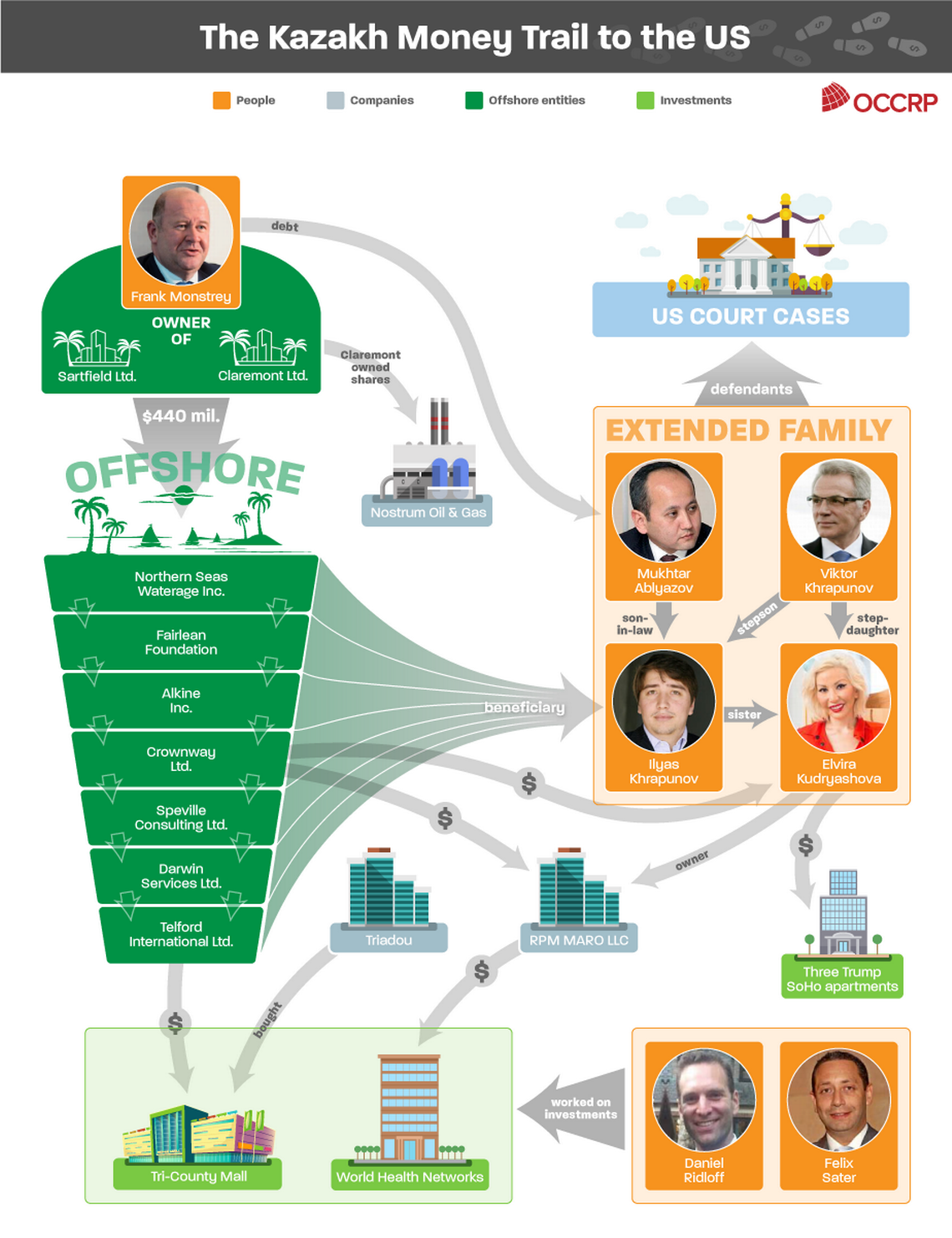

A collaborative investigation has found the specific offshore companies used to route into a Trump-branded property more than $3 million linked to a massive fraud case in Kazakhstan.

A collaborative investigation has found the specific offshore companies used to route into a Trump-branded property more than $3 million linked to a massive fraud case in Kazakhstan.

The discovery provides one of the most detailed views yet of a money-laundering allegation involving a Trump property.

The exact money trail and how it connected the Trump SoHo project in New York to Kazakh oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov has so far been hidden from public view.

The collaborative investigation involving the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, the Dutch TV documentary program Zembla and McClatchy shows how more than $30 million from an allegedly tainted source was used to finance Kazakh investments in the United States with the help of ex-Trump associate Felix Sater.

A Russian émigré, Sater was convicted of stock fraud in the late 1990s but escaped prison time by working, unbeknownst to investors and colleagues alike, as a government informant on national security issues.

Sater’s former company, international real estate and investment firm Bayrock Group, partnered with Trump to build the troubled Trump SoHo tower in New York City. It gave the Trump Organization a license fee for the use of its name and an 18 percent ownership stake in the New York hotel and condo project. The two companies also had a failed project in Fort Lauderdale called Trump International Hotel & Tower.

Felix Sater, Miami Herald file photo

Felix Sater, Miami Herald file photo

McClatchy last year outlined broadly how Kazakh money ended up in Trump SoHo, and how the Trump Organization sought to build an obelisk-shaped hotel in the Kazakh capital of Astana.

But new documents viewed by the reporting partnership reveal the complex winding trail through which money moved eventually to Trump SoHo after first going through offshore shell companies and a now-shuttered bank linked to terror financing.

The origin of the money traces to Ablyazov, who was convicted last year in absentia in Kazakhstan for the theft of billions of dollars from Bank TuranAlem, or BTA Bank, which he formerly headed until fleeing in early 2009. The bank was seized by the government, and theft allegations ensued.

From Kazakhstan to Manhattan

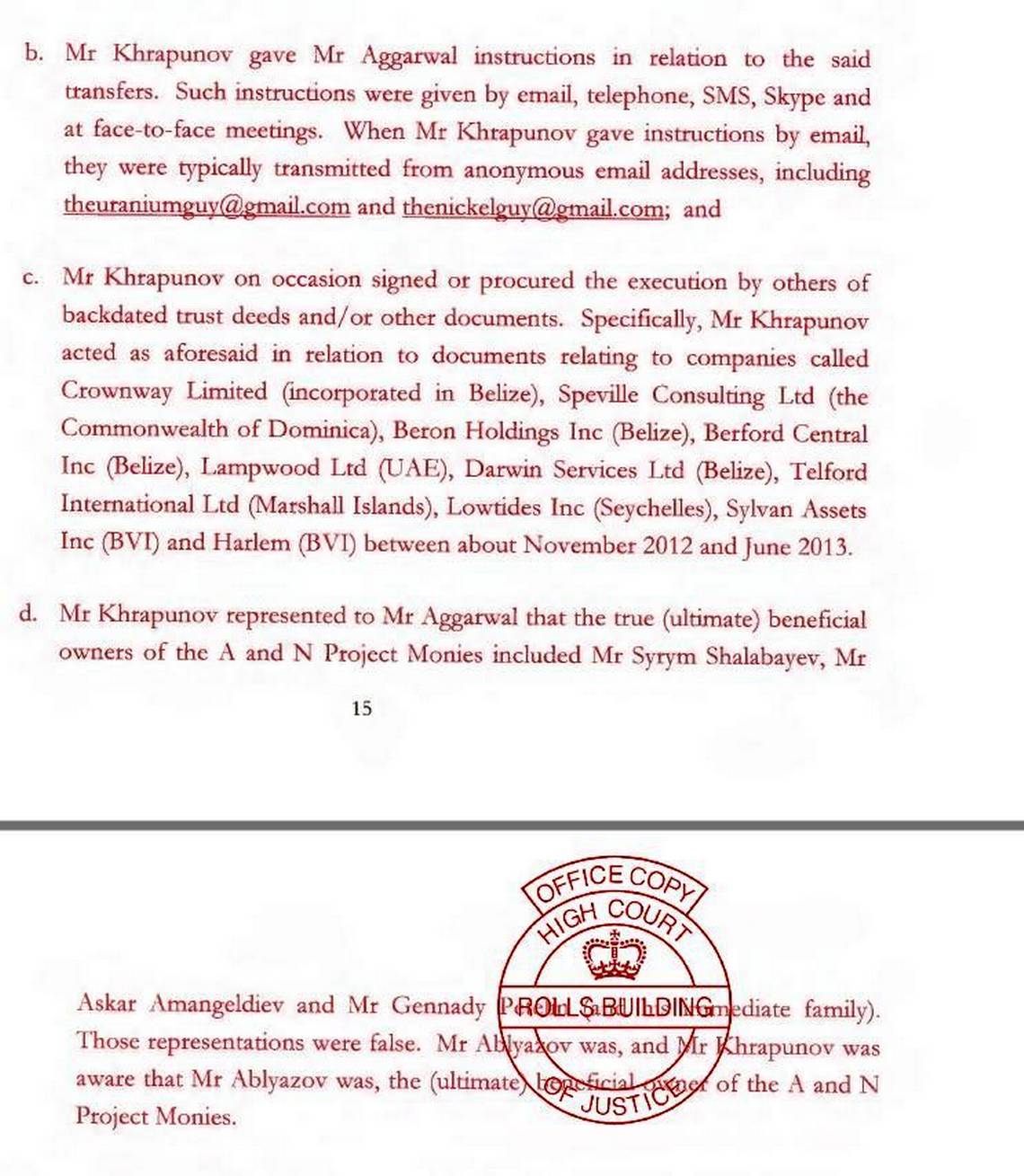

In 2016, a lawyer for BTA Bank disclosed to a British court that a private investigator had approached the financial institution with what he said was evidence that a Dubai-based offshore financial planner named Eesh Aggarwal had been building and running a network of offshore companies that were hiding Ablyazov’s money.

The private investigator, Stuart Page, presented documents he claimed were taken by Israeli computer hackers from Aggarwal’s computer, the court was told. Page did not respond to a request for comment.

Page’s documents suggested that Aggarwal had worked for Ablyazov’s son-in-law, Ilyas Khrapunov, in building and running a network of offshore companies that moved hundreds of millions of dollars between accounts held in a Tanzania-based bank called FBME.

That now-defunct financial institution had offices in Russia and Cyprus, and was sanctioned by the U.S. government in early 2016 for what was called involvement in money laundering, terror financing and arms proliferation. It is unclear whether Ablyazov-linked money factored into the U.S. action.

BTA’s own private investigators, seeking to recover what they call stolen assets, began following Aggarwal. In mid-June 2016, noticing that he had flown into Great Britain, lawyers for the bank sought and received an order from a British court to seize him and have him turn over his files.

OCCRP and its reporting partners were granted access to some of those files in late 2017 by a source with direct knowledge of the case. The files include correspondence, organizational charts, and loan and debt agreements.

The documents show that Ilyas Khrapunov — under the codename “Elvis” — was the ultimate beneficiary of a complex web of close to a dozen or more offshore companies and trusts administered by Aggarwal that handled close to $440 million via accounts at the Tanzanian bank.

This graphic from Dutch broadcaster Zembla shows Mukhtar Ablyazov, a fugitive Kazakh banker, former Almaty Mayor Viktor Khrapunov, and their children, who are married, Madina Ablyazova and Ilyas Khrapunov. All face lawsuits alleging embezzlement.

Working with documents filed in federal civil lawsuits in New York and California, reporting partners were able to piece together a trail that shows this money was used in part to finance key Khrapunov investments in the United States. These include the Trump SoHo apartments and a profitable investment in the distressed debt of an Ohio shopping mall.

Several of the emails show that Sater was involved in coordinating the transfer of millions of dollars to the United States. They also show his relationship with two immediate members of Ilyas Khrapunov's family.

In one email discussing a $3 million transaction, his stepfather — Viktor Khrapunov — tells Elvira Kudryashova, Ilyas' sister and purchaser of the three Trump SoHo condos, that Sater is “my business associate.” Other emails show Ilyas in correspondence with Sater.

Aggarwal hung up when contacted by phone by a reporter, and did not reply to a follow-up email. Sater declined to answer detailed questions sent by email.

The U.S. civil lawsuits against the Ablyazovs and Khrapunovs were brought by BTA Bank and Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city. They allege that the U.S. investments were made using commingled funds from Ablyazov as well as his relative by marriage, the elder Khrapunov, who is a former mayor of Almaty.

Ilyas Khrapunov is married to Ablyazov’s daughter Madina, and they are exiled in Geneva.

Kazakh authorities accuse the Khrapunovs of stealing more than $300 million through corrupt land deals during his time as mayor. Both families dismiss the accusations as political retribution for opposition to the country’s longtime leader Nursultan Nazerbayev, a U.S. ally.

Belgian Bucks

Using Aggarwal’s documents, the reporting team traced the money back to its original source. It was a Belgian businessman who claims to have been repaying a nearly $500 million debt to Ablyazov at a time when the fugitive banker’s assets were ordered frozen by British courts.

That businessman, Frank Monstrey, is an entrepreneur who in 2004 bought Zhaikmunai, a Kazakh oil and gas company that has since had a public offering to investors in Britain under the name Nostrum Oil & Gas.

The seized documents show that the entire $440 million that ran through the offshore network believed tied to Ilyas Khrapunov came from two companies based in British offshore tax havens belonging to Monstrey. It is why he is now part of Ablyazov’s British case.

The documents show that the offshore companies Sartfield and Claremont paid the huge sum of money over a period of nearly a year spanning 2011 and 2012. It flowed into Northern Seas Waterage, a Seychelles-registered firm said in court filings to be under Ilyas Khrapunov’s ultimate control.

Aggarwal, his financial advisor, then allegedly ran the money through the network of offshore companies, with some of it eventually ending up in the United States.

Lawyers for BTA managed to convince a British court early last year to freeze the shares that a Monstrey company held in Nostrum Oil & Gas. A month later, he resigned as Nostrum’s chairman and by mid-2017 reached an out-of-court settlement with BTA to sell his frozen shares to the bank.

In written responses to questions sent by the reporting partners, Monstrey vehemently denied being a front man for Ablyazov’s business interests.

The nearly $440 million, he said, was the repayment of a loan he had taken out years before from a Kazakh business partner. The debt was owed to the partner whose stake had been assumed by Ablyazov after the partner’s death.

“I have never been a proxy for or agent of Ablyazov or those I now know to have been associated with him,” Monstrey said. “I have unwittingly and innocently found myself sucked in to a battle between BTA and Ablyazov/Khrapunov.”

Monstrey declined to respond to detailed follow-up questions. His former company Nostrum declined a request for comment.

A spokesman for Ablyazov would not answer specific questions about the transactions, Monstrey, Sater and the Khrapunovs.

This screen shot of an amended complaint in September 2017 in a British lawsuit brought by a Kazakh bank and the Kazakh city of Almaty spells out some of the accusations against Ilyas Khrapunov and his father-in-law Mukhtar Ablyazov.

Following the money

Documents filed in U.S. court cases show that, between 2012 and 2014, Ilyas Khrapunov and Elvira were helped with their U.S. investments by Sater, the former Trump advisor, along with another ex-Trump Organization employee named Daniel Ridloff. Through a lawyer, he declined comment.

The Khrapunov investments included the $1.2 million purchase in New York of a former facility for the mentally disabled and surrounding land in Syracuse, and the purchase of shares of a health kiosk company.

The largest investment aided by the two men was the 2013 purchase for roughly $30 million of outstanding debt for the Tri-County Mall in the suburbs of Cincinnati. The mall’s debt was sold for about $45 million soon afterward.

A legal dispute ensued when Sater allegedly withheld the sale proceeds from the Khrapunovs. It was resolved only after the Khrapunov firm behind the investment agreed to let Sater keep much of the proceeds, his opponents said in a document filed in the New York case last December.

That document said that Sater was granted the settlement after his lawyer sent a letter to a Khrapunov company in October 2013 stating that Ilyas Khrapunov had told him “that the funds for several [Khrapunov] companies belonged to Mr. Ablyazov.”

The Khrapunovs deny they commingled Ablyazov money. If it was Ablayazov’s money, then it would suggest that Sater was aware he was helping invest funds that Kazakh authorities had already declared were stolen.

Bayrock's and Sater's links to the Khrapunovs date back to 2007, when Trump SoHo was under development. They set up a Dutch joint venture with Sater’s Bayrock called KazBay. It aimed at coal mining and a power deal in Kazakhstan. Bayrock and the Khrapunovs also partnered on a condominium project in Switzerland in 2008.

Britain’s highest court ruled last March that Ilyas Khrapunov can be pursued in British courts for allegedly conspiring with Ablyazov to conceal assets.

In New York, a judge that same month held Ilyas in contempt of court in March for allegedly leaking to the media a court transcript involving BTA’s current chief.

A Khrapunov spokesman did not answer requests for comment.

This story was reported in collaboration between the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, the McClatchy Washington Bureau and the Dutch TV documentary program Zembla.

Additional reporting by Kevin G. Hall and Ben Wieder in the McClatchy Washington Bureau and OCCRP's Chris Benevento, Lejla Sarcevic, Bermet Talant and, Katarina Sabados.

McClatchyDC.com, June 26, 2018