Aron Bornstein arrived in Kazakhstan in February 2009 with $84m and a daunting assignment. His job was to hand out millions of dollars to impoverished families, non-governmental agencies and students who wanted to pursue secondary education. The catch was that he could not have any dealings with the Kazakh government, which was not exactly happy to see him coming.

Aron Bornstein arrived in Kazakhstan in February 2009 with $84m and a daunting assignment. His job was to hand out millions of dollars to impoverished families, non-governmental agencies and students who wanted to pursue secondary education. The catch was that he could not have any dealings with the Kazakh government, which was not exactly happy to see him coming.

The money had been frozen in 1999 and the US later alleged that it had been used to pay illegal bribes to top Kazakh officials under Nursultan Nazarbayev, the country’s long-serving president. Now, Mr Bornstein was in Kazakhstan to give the cash back to the citizens who, according to US and Swiss authorities, it had been stolen from.

Mr Bornstein, an international aid worker, and his team set up field offices, screened local hires to weed out anyone with government ties and created a database of qualified recipients. The foundation was named Bota, or “little camel” in Kazakh.

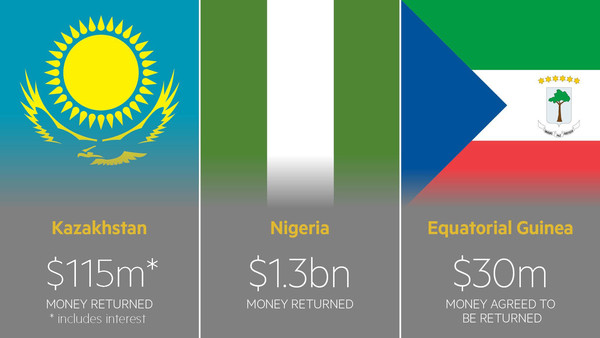

Over the next six years — two longer than projected — Bota distributed all the money Mr Bornstein had arrived with, plus $31m in interest. In that time, more than 150,000 mothers and children received nutritional assistance and early education programmes. Scholarships were handed out to 841 students.

For the US Department of Justice and its “Kleptocracy Initiative”, which was launched in 2010, Bota was a victory in the global battle against official corruption. But even supporters acknowledge that it will be hard to replicate in other countries where corruption is rampant or when larger sums of money are involved. And it was burdened by the fact that, at heart, the DoJ is a law enforcement agency, not a charity.

“It was over-bureaucratised,” Mr Bornstein recalls. “The Department of Justice is not a development agency. It just wasn’t its priority.”

It is difficult enough for law enforcement agencies to successfully bring international graft cases and seize stolen assets. But it is proving just as difficult to return the money to the citizens without it landing back in the hands of the thieves.

That quandary has become more acute as the US, UK, Switzerland and other countries extend their reach as global policemen tracking stolen assets. The World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative estimates that $20bn-$40bn a year is stolen from developing countries. Others say it could be as much as $1tn.

The US has more than $1.5bn belonging to Nigeria, Uzbekistan, Thailand and Ukraine tied up in bank accounts in various stages of litigation as part of its Kleptocracy Initiative. Earlier this year the DoJ announced forfeiture actions freezing $850m it alleges were bribes paid to Uzbek officials to award telecoms contracts.

Of that, only about $120m, or one-eighth of the frozen assets, has been returned to the victim countries.

“When you think about the money that’s stolen it’s like an inverted pyramid,” says Shruti Shah, vice-president of programmes and operations at Transparency International USA. “The top is the money that’s stolen. A smaller percentage is frozen and a minuscule percentage is actually returned.

“All government and international institutions should work harder to try to find solutions.”

The UN convention against corruption says money should be returned to the victim country without conditions. But countries including the US, UK and Switzerland have generally insisted on terms to ensure that the money is not stolen again. That often means cash is tied up in litigation.

Funding extravagance

In 2011 the US sought $80m in assets that it alleged Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of the president of Equatorial Guinea, stole and used to fund an extravagant lifestyle — a Gulfstream jet, a $30m Malibu mansion, nearly $2m in Michael Jackson memorabilia and a Ferrari. After three years of court battles, the DoJ reached a settlement with Mr Obiang agreeing to turn over $30m in assets.

He managed to keep a crystal-encrusted glove Jackson wore during the “Bad” tour and his Gulfstream jet. The DoJ plans to return the money to a charity to benefit Equatorial Guinea — but it first needs to sell the six-bedroom mansion perched above the Pacific Ocean.

Sani Abacha stole as much as $5bn when he was president of Nigeria from 1993 until his death in 1998, according to Transparency International. About $3bn of the funds are tied up in Lichtenstein, Switzerland, the UK, US, France, Luxembourg and the Channel island of Jersey. So far, $1.3bn has been repatriated and in March the Swiss announced an agreement to return another $321m.

The US agreed in 2014 to return $480m but the money is frozen awaiting court appeals by entities linked to the Abacha family.

Muhammadu Buhari, a former military ruler who became Nigeria’s president in 2015 after pledging to clean up graft in the oil-rich country, summarised the difficulties at an anti-corruption conference in London this spring. “Our experience has been that repatriation of corrupt proceeds is very tedious, time-consuming and costly,” he said.

Even with agreements, civil society groups are concerned that the Abacha money will be misused. An earlier tranche that was returned was placed in the central budget with little transparency or accountability to ensure it was spent as intended.

David Ugolor, executive director of the Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice, a civil society group in Benin City, says: “The issue of asset recovery cannot be discussed in the absence of the victim.” His organisation would like the money to go toward supporting victims of the Boko Haram Islamist group, people harmed by oil exploration and education.

“We’re very concerned about the US government putting its money where its mouth is. Too much policy without action doesn’t mean anything to Nigeria and its people,” says Mr Ugolor. DoJ officials say they will engage civil society groups after the court process is over.

Sometimes it is easier to return the cash — especially when there has been a change in power. Last year the DoJ returned $1m to South Korea that was allegedly stolen by a previous president, Chun Doo-hwan.

US prosecutors argue that the corruption cases are within their jurisdiction as long as the proceeds pass through America, whether in bank accounts, fancy cars or beachfront property.

“We want to protect the US financial system from becoming a haven for these proceeds,” says a US official. “Where you have a rotten government — those are the kinds of places where organised crime and terrorism take root.”

US officials also point to another benefit — tying up the money for years will deprive dictators from thriving off of it.

Yet some sceptics say the US is part of the problem because it allows for impenetrable shell companies that corrupt dictators can use to mask their purchases. Earlier this year, the US said it would require banks to verify who the true owners are behind accounts.

“The fact that the US, Britain, and the Swiss are a magnet for these illicit assets presents an integrity problem,” says Mr Bornstein. “The new government in power will say my guy may have stolen the money but your system allows that to happen.”

Transferring the cash

Establishing the Bota foundation was drawn out over a decade. In 1999 the Swiss government froze bank accounts linked to Mr Nazarbayev’s finance ministry on suspicion of money laundering. Four years later the US indicted an oil executive and an American businessman in an alleged bribery scheme. Both later pleaded guilty.

Kazakhstan laid claim to the money and after years of negotiations, an agreement was struck in 2007 between Kazakh officials, the Swiss, the US and the World Bank to set up an independent foundation as a way to return the funds to the country. It took another year of talks to hash out the specific terms of the pact.

Mr Nazarbayev was still in power and both the US and Swiss worked to ensure the foundation was completely independent from the Kazakh government.

After competitive bidding, the World Bank chose Irex, an educational non-profit group, and Save the Children to run the programme. Mr Bornstein was hired and dispatched to Almaty, the country’s business capital. The biggest concern when setting up the foundation was to ensure the money would not leak back to the government.

“It was a little bit of a constraint for us,” says Kathy Evans, director of Irex. “Kazakhstan is a socialist country so everything is tied to the government. We’re supposed to be working with schools and health clinics and to find any not tied to the government was challenging and not always the best alternative.”

Bota started in two regions and expanded to six. To launch a conditional cash transfer programme, which pays parents about $15 to have their children vaccinated, among other things, it opened field offices and had mobile enrolment centres that travelled from village to village.

“They used a lot of volunteers instead of government social workers,” says Penny Williams, senior operations officer for the social protection unit at the World Bank. “They found ways to abide by the commitment that it would be independent of the government.”

Bota’s work sometimes ground to a standstill as it waited for all three governments to approve budgets. “We delayed when we had to delay. It wasn’t a turn off the lights situation but we had to delay payments” to tens of thousands of individuals, says Mr Bornstein.

In one programme Bota said it delivered $56m to 154,241 beneficiaries under the cash transfer programme and 74,470 children were provided early childhood education. In another it distributed 632 grants worth $12.5m to NGOs to support the creation or expansion of social services. Of the 841 needs-based scholarships granted to poor and vulnerable youth, more than 90 per cent of the recipients were the first in their family to access higher education, the foundation said.

Bota surpassed its stated goals except one — the agreement called for it to continue “to operate as a functioning foundation”. But without the support of the Kazakh government it was wound down after the money was distributed.

“The government was quite co-operative with us but once the time period was over it wanted to be done with it. It didn’t want people asking questions,” says Ms Evans of Irex.

The project helped many poor families, but its closure has left a void.

“Nobody is working on child welfare issues on a comprehensive basis,” says Janyl Mukashova, a Kazakh who was director of Bota’s social services programme. “It’s a pity.”

Applying the model

As the US steps up its efforts to rein in kleptocrats many challenges remain. In the mobile phone bribery case, Uzbekistan has argued the $850m should be returned unconditionally since it arrested individuals in connection with the bribery scheme.

If the US prevails it will need to find a way to return the money while dealing with the same officials. There have been some discussions about following the Bota model, but the Uzbek case is of a bigger magnitude.

“Whether a Bota foundation arrangement is remotely feasible in a country as repressive and corrupt as Uzbekistan is truly a serious question that everyone is asking and scratching their heads about,” says Ken Hurwitz, head of the Open Society Justice Initiative’s anti-corruption legal work.

Some question whether prosecutors should be in the business of collecting money if they do not have clear pathways to return it. But others say patience is needed.

“For one thing [the DoJ has] only been making a serious effort for a few decades in creating what is in effect a new area of law,” he says. “There is a huge learning curve. We’re not there yet but when there is a critical mass of such cases then there becomes a deterrent effect,” he says.

THE FINANCIAL TIMES, 5.07.2016