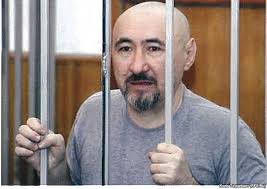

The Kazakh poet Aron Atabek has been in prison since 2007. He has been placed in solitary confinement for two years as punishment for writing a book that criticises President Nursultan Nazarbayev, and is due for return to the general prison population at the end of 2014. He has previously spent two years in solitary confinement for refusing to wear a prison uniform: one third of his incarceration so far has been spent in isolation. Both the UN Human Rights Committee and the UN Committee against Torture have concluded that prolonged solitary confinement may amount to torture.

The Kazakh poet Aron Atabek has been in prison since 2007. He has been placed in solitary confinement for two years as punishment for writing a book that criticises President Nursultan Nazarbayev, and is due for return to the general prison population at the end of 2014. He has previously spent two years in solitary confinement for refusing to wear a prison uniform: one third of his incarceration so far has been spent in isolation. Both the UN Human Rights Committee and the UN Committee against Torture have concluded that prolonged solitary confinement may amount to torture.

PEN International's Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) is asking PEN members to lobby their respective ambassadors to Kazakhstan, their respective Members of the European Parliament (where applicable), and also the Kazakh authorities, demanding that Aron Atabek be released from solitary confinement and returned to a prison within reasonable visiting distance for his family. We are also asking PEN members to write to Atabek in prison, and to highlight his situation by writing articles and contacting their national or local media.

The 60-year old poet, Aron Atabek, is currently imprisoned in what has been described as one of Kazakhstan's harshest jails. He has been in solitary confinement since December 2012 and will continue to stay there until the end of 2014: this is his punishment for writing The Heart of Eurasia, a blunt critique of President Nursultan Nazarbayev and his government.

Atabek wrote this mixture of poetry and prose whilst in jail after conviction of alleged offences relating to a 2006 clash between protesters and police that took place during the attempted demolition of a shanty town. The text was smuggled out of prison and published on the internet in 2012. When it was discovered by the authorities, Atabek was charged with violating prison rules and was transferred to a maximum security penitentiary in the City of Arkalyk, over 1,650km away from his family in Almaty, making it difficult for them to visit him.

The conditions in which Atabek is being held are extremely harsh. His son told PEN International that Atabek has not been allowed a family visit since 2010. Atabek has described the conditions of his incarceration in the two letters that his family has received since he was moved to solitary confinement. He says that he is being kept under 24-hour video surveillance and that access to writing materials, natural light, phone calls and letters from his family is denied. Every day – handcuffed and hooded – he is taken for a brief walk, during which communication with other prisoners is strictly prohibited.

This is Atabek's second period in solitary confinement; he spent two years (from 2010 to 2012) in exactly the same conditions as punishment for refusing to wear a prison uniform. He spoke about this previous stay in solitary confinement during a rare telephone interview conducted by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty shortly before he was transferred to Arkalyk.

Atabek describes his incarceration as a 'prison within a prison,' and has spent one third of his time in prison so far in isolation. Atabek has been involved in publishing, writing and political activism since the mid-1980s. He is the founder of two newspapers and author of nine books. For more than two decades his writing and activism have focused on political and social issues, and on the corruption that he believes has kept President Nazarbayev in power for the last 23 years. He is a blunt and very vocal critic of the president.

Atabek suffers from heart disease and sciatica; he received an eye injury following an alleged attack by another prisoner before his transfer to solitary confinement. Atabek's son told PEN that he fears that his father is not receiving adequate treatment for his injuries and ailments in prison. To read more about Aron Atabek, see this article by the Writers in Prison Committee's Cathal Sheerin.

To read a poem that Atabek has written whilst in prison, please see here. Kazakhstan Human rights violations – including torture by the police – are widespread in Kazakhstan. Truly independent voices, especially critical ones, are not tolerated: many of those who report on official corruption or who have protested or reported critically on the December 2011 police massacre of at least 15 striking oil workers in Zhanaozen have been imprisoned, or their publications banned. Kazakhstan was elected to the United Nations Human Rights Council in November 2012, and took up its seat in January 2013. Kazakhstan ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 2006 and the Convention against Torture in 1998.

At its last Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the United Nations in 2010, Kazakhstan accepted a number of recommendations from states regarding torture and prison conditions. These recommendations were:

•To establish torture as a serious crime punished with appropriate penalties, in keeping with the definition set out in the Convention against Torture (Australia);

•To continue efforts to eliminate torture and improve the conditions of detention and the protection of the rights of detainees, and to share relevant experiences with interested countries (Algeria);

•To continue to apply a zero-tolerance approach to torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Germany);

•To amend the law in order to ensure that torture is established as serious crime punished with appropriate penalties and ensure that it is brought into full conformity with the definition set out in the Convention against Torture (Germany);

•To further improve prison conditions (Azerbaijan);

•To improve the standards and the situation of human rights in prisons, and to carry out an independent investigation into cases of violence in prisons (Slovenia) Solitary Confinement

In 2011, the Special Rapporteur on Torture reported on solitary confinement to the UN's General Assembly. He found solitary confinement to be 'contrary to one of the essential aims of the penitentiary system, which is to rehabilitate offenders and facilitate their reintegration into society.'

He also noted that: 'Where the physical conditions and the prison regime of solitary confinement fail to respect the inherent dignity of the human person and cause severe mental and physical pain or suffering, it amounts to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.'

There is an absolute prohibition on the use of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment under international law (Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention against Torture (CAT), for example). The UN Human Rights Committee has concluded that use of prolonged solitary confinement may amount to a violation of Article 7 of the ICCPR (General comment 20/44, 3. April 1992). The UN Committee against Torture has made similar statements. Principle 7 of the UN Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners states that 'Efforts addressed to the abolition of solitary confinement as a punishment, or to the restriction of its use, should be undertaken and encouraged'.

In his recommendations to the Human Right Council in 2011, the Special Rapporteur urged States to 'prohibit the imposition of solitary confinement as punishment — either as a part of a judicially imposed sentence or a disciplinary measure.' He also advised that 'prolonged solitary confinement, in excess of 15 days, should be subject to an absolute prohibition.'

PEN regards Atabek's prolonged stay in solitary confinement, the harsh conditions in which he is being kept, the blocking of communications between the poet and his family, and his lack of access to writing materials, as a cruel and inhuman punishment that violates the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment and that runs contrary to the recommendations made by the Special Rapporteur on Torture.

The UN's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, adopted in 1955 by the First United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, states: 'Prisoners shall be allowed under necessary supervision to communicate with their family and reputable friends at regular intervals, both by correspondence and by receiving visits.' Kazakhstan is violating these basic rules by denying Atabek access to visits from his family and to regular correspondence with them.

We call on the Kazakh authorities to release Aron Atabek from solitary confinement immediately, and to return him to a prison within reasonable visiting distance for his family.

www.penusa.org