Uzbekistan’s so-called “spring” is more about upgrading this Central Asian state than providing political freedoms.

Uzbekistan’s so-called “spring” is more about upgrading this Central Asian state than providing political freedoms.

Seventy kilometres south of Tashkent, Pengsheng Industrial Park is the biggest non-energy cooperation project between China and Uzbekistan. Photo: Zhou liang / Xinhua News Agency / PA Images. All rights reserved.Understanding the configuration of political change in Central Asia is traditionally a challenging task. The temptation to examine the region’s authoritarian evolution through a lens of persistent stagnation has proven very hard to resist: such approaches ultimately contributed to the consolidation of a peculiar analytical standpoint, which identified a leader’s death as the exclusive harbinger of change in the region. Everything will get better, but only after the president dies.

This mantra brings with it two analytical pitfalls. To begin with, it reduces any alteration of Central Asia’s authoritarian governance to an inevitably positive process. This diminishes the analytical relevance of downward authoritarian trajectories similar to those recently experienced by Kazakhstan and, more extremely, Turkmenistan. In doing so, it obfuscates our understanding of the consequences of a leader’s death: these consequences must be positive, given that they are part of an essentially new landscape where the authority of a late president has all but disappeared. When the “zero hour” comes, governance standards are bound to be lifted. Some of the positive views of early post-Niyazov Turkmenistan were certainly inspired by this narrative, which, nevertheless, recently resurfaced to shape more decisively the international perception of what is going on in post-Karimov Uzbekistan.

After the death of Islam Karimov in August 2016, predictable references to an elusive “Uzbek spring” have shaped many of the reports published by prominent international media outlets. Indeed, this term is used to describe the political landscape that has emerged in Uzbekistan after Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power. Some of the flagship initiatives put into place by the new regime strengthened this narrative: the re-establishment of contacts with international human rights organisations and international broadcasters, the accreditation of foreign journalists and the release of unjustly incarcerated local media operators, the introduction of full convertibility for the som and some embryonic attempts at reforming the local cotton industry suggest that something is actually changing in Uzbekistan.

As I have argued, however, it is Mirziyoyev’s new regional policy that we should pay attention to: the reopening of arbitrarily closed borders, the re-establishment of interrupted transit routes and the inauguration of new connectivity options (railways, flight paths, bus routes, energy networks) led to enormously beneficial influences on the lives of ordinary Uzbeks, particularly in those border communities that suffered most dramatically from Karimov’s isolationist trends. From whatever perspective we look at it, Mirziyoyev’s conceptualisation of change is not based on a linear process: Uzbekistan’s “spring” has been known to experience periodic “frosts” linked to the persistence of consolidated non-democratic practices that have survived the leader who originally introduced them or, in turn, the emergence of relatively new authoritarian strategies that accompanied the attempts to consolidate the mandate of the new president.

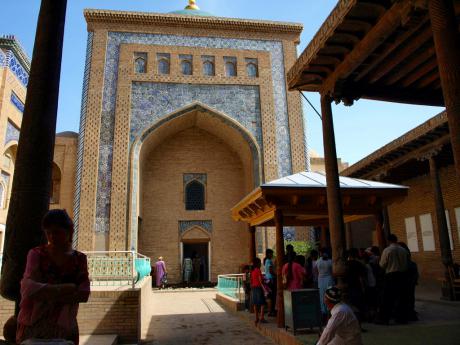

Khiva, Uzbekistan. Photo CC BY-NC 2.0: Vladimir Varfolomeev / Flickr. Some rights reserved.It is precisely at this juncture that a comprehensive reassessment of the policy framework promoted by the new Uzbek regime becomes an indispensable step towards a correct framing of Mirziyoyev’s controlled opening. For the last two years, I have been researching the politics of change in Uzbekistan, looking comparatively at Mirziyoyev’s policy initiatives in the economic and political realms and a defined set of analogous developments that emerged during the first two years of Gurbanguly Berdimukhamedov’s presidency in Turkmenistan – the only other Central Asian state to have experienced a leadership transition out of a presidential death.

Khiva, Uzbekistan. Photo CC BY-NC 2.0: Vladimir Varfolomeev / Flickr. Some rights reserved.It is precisely at this juncture that a comprehensive reassessment of the policy framework promoted by the new Uzbek regime becomes an indispensable step towards a correct framing of Mirziyoyev’s controlled opening. For the last two years, I have been researching the politics of change in Uzbekistan, looking comparatively at Mirziyoyev’s policy initiatives in the economic and political realms and a defined set of analogous developments that emerged during the first two years of Gurbanguly Berdimukhamedov’s presidency in Turkmenistan – the only other Central Asian state to have experienced a leadership transition out of a presidential death.

Preliminary results indicate that, in both contexts, the power position enjoyed by the new leader at the time of his predecessor’s death significantly influenced the new regime’s attitude towards change. Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan’s prime minister at the time of Islam Karimov’s death (27 August 2016), had therefore more opportunities to rapidly introduce change than Berdymukhamedov, who, at the time of Niyazov’s passing (21 December 2006), was sitting at the margins of the presidential circle. These findings do not however suggest that Mirziyoyev has to be seen as a genuine reformer: echoing the conclusions advanced in an important EurasiaNet article, I would argue that analytical misrepresentations of the constituent elements of change in Uzbekistan are giving the government currently in power in Tashkent a “free pass”.

Shavkat Mirziyoyev is trying to modernise, rather than liberalise, Uzbek authoritarianism. His agenda of authoritarian modernisation is oriented towards the achievement of rapid economic growth, to be pursued through sustained attempts to globalise the Uzbek economy, abandoning in the shortest time-frame possible the autarkic model that defined the political economy of the Karimov regime. In this sense, the current Uzbek president demonstrates some fluency in the governance methods of the Soviet Union, which placed modernisation at its policy-making core, while maintaining a very close alignment to Central Asia’s fundamental rule of policy reform: economy first, politics never. There is no dilemma of simultaneity for Mirziyoyev: we have heard numerous policy announcements about the need to improve Uzbekistan’s economic performance, its re-engagement with regional trade partners as well as international financial institutions (IFIs), while no significant step has been taken towards the establishment of genuine political pluralism in the Uzbek domestic political landscape. It is the attraction of foreign investment, rather than the liberalisation of the domestic political landscape, that represents the ultimate goal for élites in Tashkent.

Looking at Mirziyoyev’s policies through the lens of authoritarian modernisation does also allow us to align more closely the post-Karimov transition to Central Asia’s authoritarian norm. Mirziyoyev’s emphasis on economic openness echoes the fundamental policy line that, for over a quarter of a century, guided the authoritarian strategies implemented by Nursultan Nazarbayev in neighbouring Kazakhstan. Borrowing heavily from Nazarbayev’s playbook, the Uzbek leader and his close associates are establishing a soft(er) authoritarian regime that is simultaneously globalisation-friendly and image-savvy, while remaining intolerant to criticism and uninterested in political pluralism. Looking at today’s Kazakhstan, we may identify some of the features that could define Uzbekistan in a decade or so.

Two final considerations capture the real rationale behind the regime’s deliberate choice to modernise Uzbek authoritarianism. To begin with, authoritarian approaches based on the delivery of economic growth aim to compensate the legitimacy gap that Mirziyoyev has inevitably inherited by taking over from the first president: the clout that ordinary Central Asians recognised to Karimov, Nazarbayev, and Niyazov is not to be automatically transferred to second-generation leaders, who are therefore expected to “work harder” if they are to achieve similar levels of popularity. The severe economic crisis that is currently hitting Turkmenistan has unveiled the risks associated with the preservation of production structures dominated by the Soviet economic logic. This ultimately reveals that, in Central Asia, the era of economic autarky is rapidly approaching its end. There is no reason to believe that Mirziyoyev and his entourage are not looking with interest at what is happening in Ashgabat, inasmuch as they identified economic reform as the cornerstone of the agenda of change they have advanced since December 2016.

Focusing on Mirziyoyev’s authoritarian modernisation strategy suggests that the understanding of change framed by the Uzbek leader has neatly separated between the delivery of economic growth and the qualitative improvement of Uzbekistan’s governance. While this conclusion may not ultimately be optimistic, it certainly delineates a more adequate approach to making sense of political change in a country that, very much like its surrounding region, has been exclusively analysed through the lens of stagnation and immobility.

openDemocracy, 9 July 2018