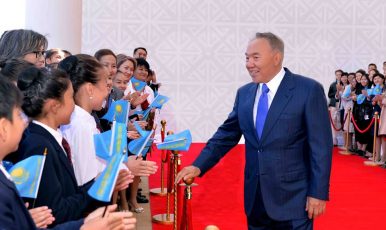

A new banknote with Nazarbayev’s image and a possible eponymous renaming of Astana may signal a potential departure.

A new banknote with Nazarbayev’s image and a possible eponymous renaming of Astana may signal a potential departure.

Issued to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Kazakhstan’s independence from the Soviet Union, the new 10,000 tenge note is worth more than its nominal exchange value of around $30. It features a portrait of President Nursultan Nazarbayev, his first appearance on Kazakhstan’s often glitzy currency. Official news outlets have forecasted that people will likely try to get a hold of the banknote and keep it as a souvenir, but the celebratory issue might mask more significant developments.

Arguably, this could be another step toward Nazarbayev’s soft self-exile from the presidency, as he continues to build for himself the image of Leader of the Nation, “Yelbasy,” a sage figure that sits above politics and symbolizes the constitutional harmony in the country. Proponents of this argument, which has recently gained currency, speculate that Nazarbayev could step down within months, although there has been no sign of the emergence of a likely successor.

In a move to make the anniversary even more memorable, this week the lower house of the parliament approved a proposal to rename the capital city after Nazarbayev. Unsurprisingly, the proposal was approved unanimously and Nazarbayev will have to adopt it or turn it down in the coming weeks. When the president moved the capital from Almaty to Tselinograd in 1997, he chose to rename the city Astana, “capital” in Kazakh, a decision that many saw as a placeholder for his own name.

The latest highly symbolic moves and declarations around Nazarbayev have exceeded the previous orthodoxy of a mild personality cult, said Luca Anceschi, lecturer of Central Asian Studies at the University of Glasgow.

“This is turning into an excessive, almost Turkmen-style, cult of personality. Decisions like these narrow the gap between Kazakhstan and the neighboring regimes. And this could be a sign of transformation in the domestic power balance,” Anceschi told The Diplomat in an interview.

Despite tirelessly admitting that this will be his last term as president, Nazarbayev seems eager to leave yet another mark, as if the crafting of the capital Astana to his own image and winning virtually unopposed elections had not been enough. Never mind that he has, in the past, criticized the very concept of putting a living leader’s face on a banknote.

As he said in his 2006 book Kazakhstan’s Path, Nazarbayev had turned down an earlier proposal to feature on Kazakhstan’s money. To eager artists, Nazarbayev replied: “Only future generations will have a say on whether my personality should be regarded as historic and hence be featured on banknotes.” With a pinch of disdain, he then added that apart from a few African leaders, no living head of state puts their face on national currency.

Conveniently for his argument, Nazarbayev avoided mentioning that Queen Elizabeth II, technically a head of state, lends her smile to banknotes in the U.K. and several other Commonwealth countries. Ten years later, Nazarbayev can now comfortably sit at the leader-for-life table and can thus let his face appear on banknotes.

Central Asia is used to presidents shaping personality cults their own way, even by putting their faces on currency. In Turkmenistan, a banknote featuring a portrait of former President Saparmurat Niyazov was in circulation until 2008, two years after his death. In Tajikistan, several organizations have lobbied to produce a new banknote worth 1,000 somoni ($130) carrying a portrait of President Emomali Rahmon.

Kazakhstan’s banknotes have often featured colorful and highly-symbolic designs. The tenge won three consecutive Banknote of the Year awards from the International Bank Note Society. The first winner was the 10,000 tenge in 2011, a celebratory issue for the 20th anniversary of the country’s independence. The new 10,000 tenge will be released on December 1, which marks the Day of the First President in Kazakhstan. Only 100,000 units of the special issue will circulate.

“These symbolic measures could ultimately weaken the power of the president and turn Nazarbayev into a poster boy of the country’s unity. As it seems increasingly likely that he will maintain the promise to step down in 2020, the debate on succession is gaining momentum in Kazakhstan,” Anceschi said.

Should Nazarbayev choose the path of becoming a president emeritus of some sort, he will set a precedent among post-Soviet autocracies, where lifelong power is the norm. The question, though, is whether he will be able to manage the transition smoothly and let one of his allies – or even family members – take over. In the meantime, he’ll be adding banknotes and, possibly, the capital city’s name to his collection of self-celebratory memorabilia.

Thediplomat.com, 24.11.2016