As oil-rich Kazakhstan votes for a president Sunday, the governing elite is pounding home a mantra of stability as fears percolate about the country's massive Russian minority taking inspiration from the Moscow-backed insurgency in Ukraine.

As oil-rich Kazakhstan votes for a president Sunday, the governing elite is pounding home a mantra of stability as fears percolate about the country's massive Russian minority taking inspiration from the Moscow-backed insurgency in Ukraine.

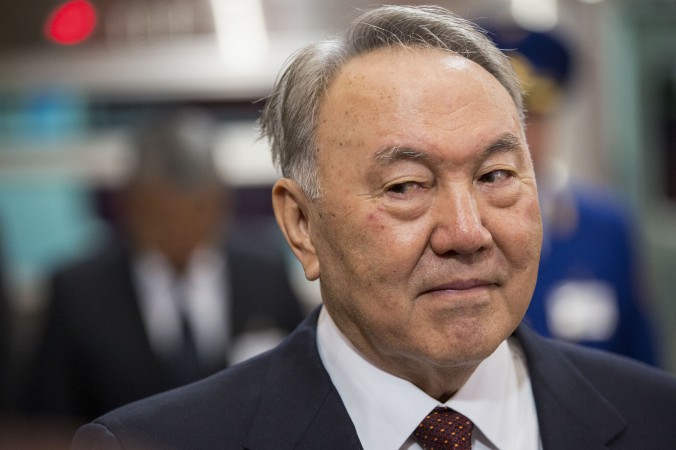

With authorities clamping down on all opposition, Nursultan Nazarbayev's re-election is a done deal. The former Communist party boss' two rivals — a trade union leader and a Communist politician— have negligible public profiles and are standing only to create the illusion of competition.

Instead of electioneering in the traditional sense, the 74-year-old Nazarbayev's team is rehearsing well-worn refrains on social and ethnic harmony.

Kazakhstan's vast diversity of peoples — from Uzbeks to Koreans and Chechens to Tatars — is a source of both pride and anxiety.

Russians are by far the largest minority, accounting for almost one-fourth of the 16 million people spread across a land four times the size of Texas.

Recently, niggling anxieties about the potential for such a large ethnic group to pursue a separatist agenda have been rekindled by unrest in Ukraine, where ethnic Russians have been goaded by Moscow into mounting an armed insurrection.

Those concerns were only deepened in August, when Russian President Vladimir Putin paid a back-handed compliment to Nazarbayev, who took charge in Kazakhstan in the late 1980s.

"He has done a unique thing. He created a state where no state ever existed. The Kazakhs never had a state," Putin told a gathering of pro-Kremlin youth activists.

Ukrainians have become accustomed to hearing Russian chauvinists declaring their country a recent invention. So Kazakhs felt a chill when they heard Putin make similar remarks about their own country.

Nazarbayev acted swiftly in the post-independence years of the early 1990s to sideline the grassroots Slavic groups, who militated for language rights and autonomy for Russians living in northern regions.

Moscow currently enjoys warm diplomatic and economic ties with Kazakhstan, as did Ukraine before the president there was toppled in a pro-Western uprising. A sudden change in Kazakhstan's trajectory could, some fear, re-ignite calls for autonomy. That's one reason why Nazarbayev is at pains to stress national harmony and close ties with the Kremlin.

Nazarbayev has also been disciplined in keeping Kazakh nationalists on a short leash.

Tight control over the media has ensured that news of occasional clashes, such as those that occurred earlier this year between Kazakhs and ethnic Tajik communities in the southern village of Bostandyk, do not travel far.

The higher official status of the Kazakh language is promoted as gingerly as possible, to avoid causing offense. The language question is treated so cautiously, in fact, that it is rare for Russians to bother learning Kazakh at all, although authorities are trying to change that by pushing its use among the very young.

Also, all prospective candidates for the presidential election were made to take a Kazakh language test. Many failed.

The weekend presidential election was preceded Thursday by a congress of the Assembly Peoples of Kazakhstan, a talking shop devoted to cultivating national unity. Before the event, Nazarbayev met with the deputy head of the assembly to discuss "Kazakhstan's model for interethnic harmony," the president's office said.

It is widely accepted that as long as Nazarbayev is around, inter-ethnic tensions will likely be kept at bay.

Speaking at Thursday's congress, he declared that the authorities would "robustly prevent any form of ethnic radicalism, regardless from where it arises."

But the fear is that Nazarbayev's successors could seek to cheaply bolster their mandate by striking a populist nationalist chord.

Nazarbayev has given no clues about heirs, however, leaving political observers to speculate idly about the future.

Associated Press, April 24, 2015