So reads the blue plaque on this pretty Georgian terraced house, home to London’s Sherlock Holmes Museum. In a city of storied buildings, the home of the fictional detective is as famous as they come.

So reads the blue plaque on this pretty Georgian terraced house, home to London’s Sherlock Holmes Museum. In a city of storied buildings, the home of the fictional detective is as famous as they come.

Sherlock Holmes

Consulting detective

1881-1904

So reads the blue plaque on this pretty Georgian terraced house, home to London’s Sherlock Holmes Museum. In a city of storied buildings, the home of the fictional detective is as famous as they come. The museum is also not the original location of the fictional detective’s fictional house. If you’re facing the museum and peer to the left, you’ll see an Art Deco cluster of flats and offices. This houses the original 221b Baker Street.

In the 21st century, the original location has fallen far off its pedestal as the home of Britain’s most famous gentleman crime-fighter. Instead, it now symbolizes a very modern London trait: the city as a mecca for money stashed away by the elites of corrupt countries.

Valued at more than £130 million ($183 million), the property spanning 215 to 237 Baker Street is held via a web of secretive offshore corporations which hide its owner’s identity. It is notorious among anti-corruption activists: In 2015, then-prime minister David Cameron singled out allegations about the property in a speech in Singapore, insisting, “We need to stop corrupt officials or organised criminals using anonymous shell companies to invest their ill-gotten gains in London property.” Two years later, the government cited the buildings in its 2017-2022 Anti-Corruption Strategy (pdf, p.37).

Anti-corruption organizations have previously investigated the properties, and postulated possible secret owners for them. Now, court documents seen by Quartz and files leaked in the Panama Papers suggest the properties have belonged at least in part to one or more family members of Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

The impenetrable nature of offshore secrecy makes unravelling who exactly in the Nazarbayev circle owns the buildings a task worthy of Holmes himself. But Quartz’s reporting suggests that, among others, Nazarbayev’s grandson Nurali Aliyev is tied to the property and his daughter, Daria Nazarbayeva, also may be linked. Despite both having spent many years in government jobs, both daughter and grandson have accrued hundreds of millions in private wealth, according to Forbes Kazakhstan.

High-profile cases like Baker Street pose an important test of Britain’s commitment to bring transparency to the ownership and control of companies there. What better place to start than the mysterious original “home” of Sherlock Holmes?

A scandal near Belgravia?

Corruption is rampant in Kazakhstan. The former Soviet country, which has among the biggest oil and gas reserves in the world, ranks 122nd out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s global corruption index.

“It’s a big national problem,” says former Kazakh prime minister Akezhan Kazhegeldin, who used to work under Nazarbayev and is now part of the opposition in exile. “A small group of people took over control of the country, its law enforcement agencies, security apparatuses, and are using it as protection in their self-enrichment scheme.”

Meanwhile, countries like the UK enable kleptocrats from all around the world, by sheltering looted capital. “The UK and US are at the forefront of providing international services” for the super-rich to “whitewash the trail of your illicit proceeds and…launder your own reputation,” says Alexander Cooley, director of Columbia University’s Harriman Institute and co-author of Dictators Across Borders: Power and Money in Central Asia.

The Baker Street properties have long seemed a part of this pattern. In 2015, a report by anti-corruption organization Global Witness suggested their ownership was tied to Rakhat Aliyev the ex-son-in-law of the Kazakh president, and former Kazakh security deputy chief, who died in mysterious circumstances in an Austrian jail cell that same year. But lawyers at BCL Burton Copeland, which represents the nominee director of the holding company that owns the properties, firmly denied that Rakhat Aliyev had ever been an owner.

Could it instead belong to other members of Aliyev’s family, such as his son Nurali or ex-wife Dariga?

“This is the £130 million question,” says Tom Mayne, who co-researched Global Witness’s report on the properties. “The company has ruled out Rakhat, so this leaves Nurali and Dariga,” he said. BCL Burton Copeland did not respond to Quartz’s inquiries about whether Aliyev’s ex-wife Dariga Nazarbayeva or son Nurali Aliyev had ever owned any portion of the properties.

Nazarbayeva, a senior Kazakh senator and former deputy prime minister, has long been rumored to be in line to succeed her father as Kazakhstan’s president. Her son, Nurali, former deputy mayor of Astana, Kazakhstan’s capital, has been the subject of similar succession rumors. Both are part of “a whole category of billionaires across Eurasia and the developing world whose income origins remain relatively murky and unknown,” says Cooley.

It’s normally easy to find out the shareholders of a family-owned company in Britain. UK-registered companies have to publicly list anybody who owns more than 25% of their shares as a person of significant control (pdf, p.2). However, Farmont Baker Street, the private limited company registered as the owner of the Baker Street buildings, says in its corporate filings that no one fits that description in this case—which has kept the identity of its owners hidden. If the paperwork was filled out correctly, that would imply there are five or more owners who each own 24% or less of the company.

Mayne and Kazhegeldin say Nazarbayeva and Nurali’s ties to the building should be investigated. “Any money from people related to [president Nazarbayev’s] inner circle arriving in the West—especially in the EU and UK—must be treated as suspicious,” says Kazhegeldin. In 2016, investigative journalism non-profit the OCCRP concluded from the Panama Papers that Nurali had stashed assets offshore.

John Mann, a backbench Labour MP who has long railed against offshore money laundering, agrees that authorities should investigate the properties—and the market as a whole. “The government need[s] to consider carefully how to clamp down on any abuses, and use the full force of the law’s existing powers on money laundering and unexplained wealth to find out what has really been happening,” he said in a written statement.

To be clear, there is no evidence or allegation that Nurali or Nazarbayeva has been involved in corrupt or illegal activity, or that they have used illicit funds to purchase the Baker Street properties. But there is little question that both are fantastically wealthy: Forbes Kazakhstan considers both of them to be worth hundreds of millions, and ranked the mother and son as among the 50 richest Kazakhs in 2012 and 2013.

But what points to Nazarbayeva and Nurali as likely owners of the building? That, dear reader, is elementary.

The case of the unused yacht

In early 2008, things were looking pretty good for Nurali Aliyev. Then just 23, the Kazakh president’s grandson was chairman of Nurbank, one of the country’s biggest private banks. By the end of the year, he would be named deputy chair of the state-owned Development Bank of Kazakhstan. He lacked one thing though: a really nice yacht.

So he bought one, named it “Nomad,” and insured it for €2 million, reports investigative journalism non-profit OCCRP. But the yacht was reportedly damaged in bad weather, and Nurali seemingly never got to use it, OCCRP reports, based on information in the Panama Papers. Many of the relevant Panama Paper files, obtained by German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, were shared with Quartz.

The yacht’s short life saw its ownership pass through at least three holding companies in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). Owning assets through offshore companies provides several benefits for super-rich individuals from countries with potentially fragile political systems. They hide the owner’s identity, make it difficult for authorities back home to seize the properties (should power ever change hands or the owner fall out of favor), and holding assets through the BVI can provide tax benefits.

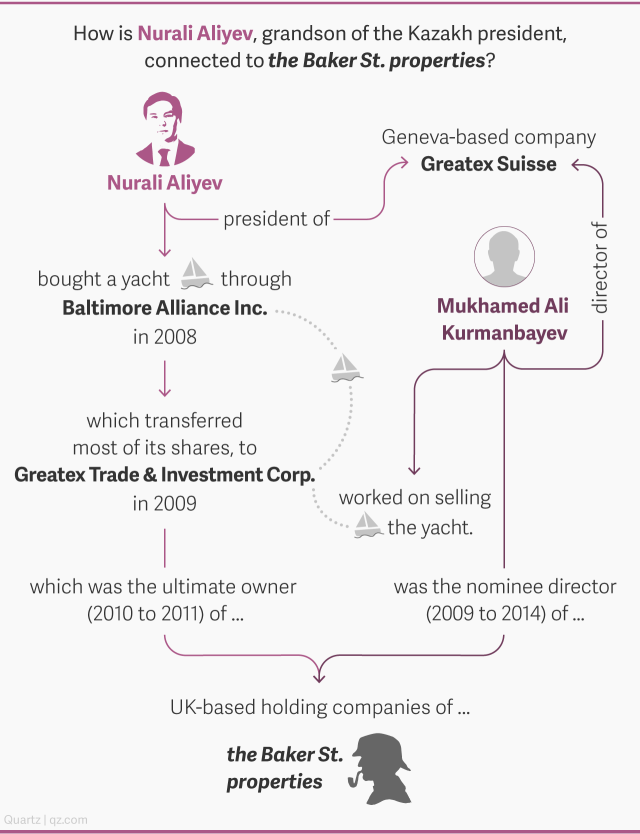

Nurali eventually sold the yacht back to its manufacturer in 2011 via BVI firm Greatex Trade & Investment Corp, according to OCCRP. In 2010-2011, that company was also the ultimate owner of the UK companies that owned the Baker Street properties, according to company files.1

The UK companies holding the Baker Street properties and the ones through which Nurali owned the yacht counted among their staff the same man: Mukhamed Ali Kurmanbayev, whose LinkedIn profile says he is a “specialist in luxury assets—aircraft, yachts, real estate.”2

Kurmanbayev worked for Nurali as early as 2007 and appears regularly in offshore companies linked to Nurali, the OCCRP reports. He was granted power of attorney (pdf) to sell Nurali’s yacht in July 2011. At the same time, he was also the sole nominee director of all three UK-registered companies that bought the Baker Street properties. He held that position from 2010 to 2014 for all three companies, and some for longer.3

The fact that Nurali’s yacht and the Baker Street properties were ultimately owned by the same BVI holding company at the same time points to Nurali as the likely owner of at least some portion of the properties during at least 2010-2011. Nurali did not respond to requests for comment sent via his assistant and to his social media. Kurmanbayev’s lawyer didn’t respond to requests for comment.

UK-registered Greatex also held the leases of two properties near London’s Hyde Park, according to Global Witness, one of which was then sold to a company in the offshore island tax haven of Jersey.

The adventure of the mysterious Italian

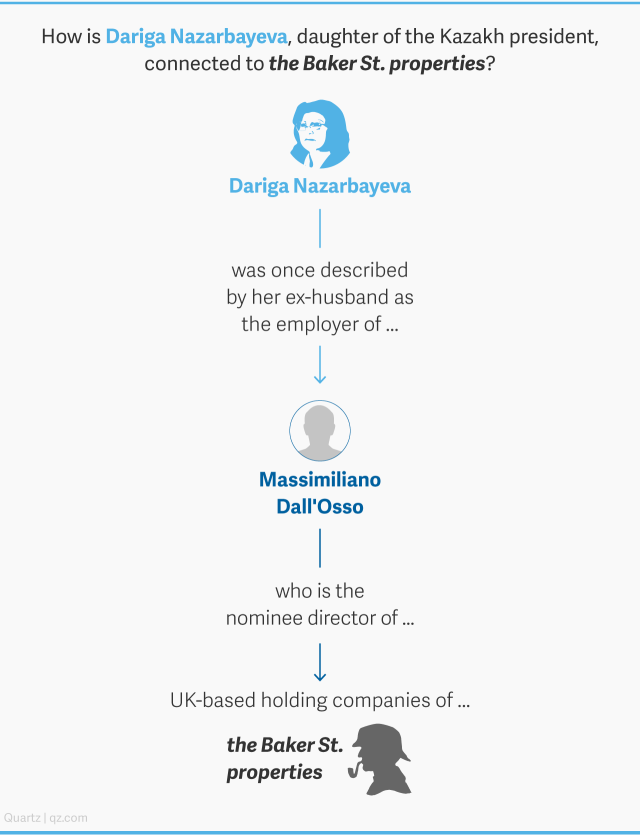

Kurmanbayev wasn’t the only nominee director of the Baker Street holding companies. Nor was he the only one connected to Kazakhstan’s first family. In 2014, he was replaced by an Italian named Massimiliano Dall’Osso, who remains nominee director to this day.

Dall’Osso links Nurali’s mother, Dariga Nazarbayeva, to the Baker Street properties.

The 53-year-old Italian has a long and convoluted relationship with Kazakhstan’s first family. In 2005, Dall’Osso became the managing director of a German metallurgy company that belonged to Rakhat Aliyev (Nurali’s father and Nazarbayeva’s ex-husband) and his second wife, Elnara Shorazova, and was on the board of its Austrian parent company, according to court documents seen by Quartz. Aliyev was questioned in Malta in 2012 by Austrian prosecutor Bettina Wallner, who was investigating allegations made by the Kazakh state about Aliyev’s alleged role in the torture and murder of two bankers in Kazakhstan in 2007.4 Dall’Osso’s lawyer didn’t respond to requests for comment.

While Aliyev and Dall’Osso seem to have parted ways by 2007, the Italian apparently grew close to Aliyev’s ex-wife, Nazarbayeva. In the same interview, Aliyev told the prosecutor that Dall’Osso now worked as a “personal assistant” to Nazarbayeva.5

Christian Leskoschek, an Austrian lawyer who knew both Nazarbayeva and Rakhat Aliyev, confirmed to the same prosecutor in September 2012 that Nazarbayeva knew Dall’Osso—calling him an acquaintance of hers. Nazarbayeva didn’t respond to requests for comment sent through her assistant and her parliamentary website. Leskoschek didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Dariga Nazarbayeva stands with her father, president Nursultan Nazarbayev, alongside Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip. (Reuters/Chris Jackson)

A Study in Secrecy

The Baker Street case is a drop in the ocean of secretive London real estate. Around 86,000 British properties have their ultimate owners hidden by offshore companies, with Transparency International estimating that £4.2 billion worth of London real estate is owned by people whose wealth comes from suspicious sources. TI found in 2017 that 90% of properties owned by “high corruption risk individuals” were held by British Virgin Islands companies.

The fictional hit BBC series McMafia—about a British-Russian mafia family living in London—has awakened the public to Britain’s role in international crime, and the British government promised this year to step up its battle against corrupt money.

Separately, a new law has just come into force, allowing authorities to require a person to explain their stake in a property and how they came to own it, if they are suspected of connections to “serious crime” and the owner’s income seems disproportionate to the property’s value.

Authorities have already used this to target two London homes worth a combined £22 million, reportedly belonging (paywall) to a Central Asian politician. “We will come for you, for your assets and we will make the environment you live in difficult,” security minister Ben Wallace has warned.

As is its policy, the National Crime Agency declined to comment on whether there is or ever had been an investigation into the Baker Street properties.

Tourists gather in front of the Sherlock Holmes museum. (Elizabeth Dalziel for Quartz)

Tourists gather in front of the Sherlock Holmes museum. (Elizabeth Dalziel for Quartz)

The “great cesspool”

Britain’s permissive attitude to shady money hurts the country in a plethora of ways. It diminishes its soft power, as Westminster preaches transparency abroad while letting money allegedly stolen by corrupt elites into its own markets. It endangers national security, potentially allowing foreign powers and terrorist organizations to shovel cash into Britain, without authorities knowing who’s behind it. And it makes British homes unaffordable for normal people, with housing prices artificially juiced by oligarchs safeguarding money in empty real estate.

Holmes’s sidekick Dr Watson described the British capital as “that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.” Today, the city’s role as the endpoint in the global offshore system drains money from developing countries, whose governments see money creamed from their budgets, only to reappear in London’s finest properties.

Quartz Media, April 05, 2018