Regime Classification: Consolidated Authoritarian Regime

Regime Classification: Consolidated Authoritarian Regime

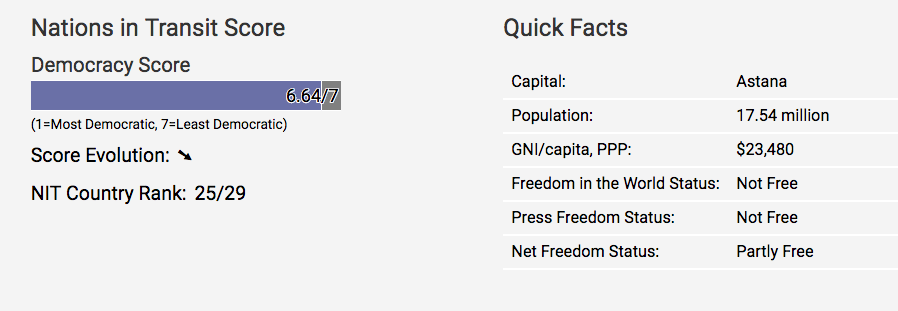

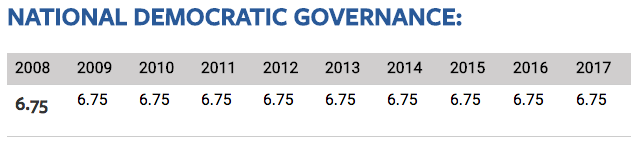

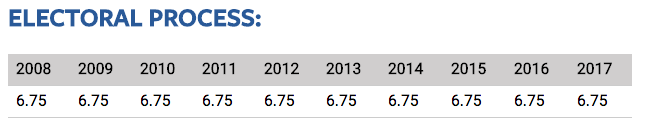

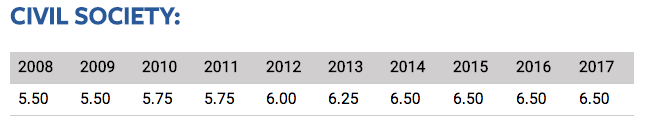

Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores

NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. If consensus cannot be reached, Freedom House is responsible for the final ratings. The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s).

Score Change:

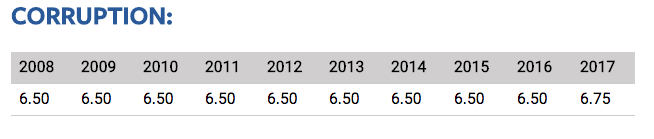

Corruption rating declined from 6.50 to 6.75 due to ample evidence of pervasive corruption, including through high-profile cases of embezzlement around Kazakhstan’s hosting of EXPO 2017, and the release of documents showing the president’s grandson owning valuable assets in offshore accounts despite the president’s call for Kazakhstanis to repatriate their wealth.

As a result, Kazakhstan’s Democracy Score declined from 6.61 to 6.64.

By Joanna Lillis

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

- In 2016, Kazakhstan remained a consolidated authoritarian regime. The heavy-handed official response to an outbreak of peaceful public protests in the spring demonstrated that official intolerance towards any form of dissent remains the norm. The catalyst for the demonstrations were reforms which would have expanded the sale of land to private investors, a measure the government deemed vital to boost agricultural investment, but which opponents resisted on the grounds that land is a national asset and should be publicly owned. The faltering economy—which slowed for the third year running in 2016 to 1 percent growth, owing to a combination of low oil prices and economic downturns in neighboring Russia and China—also played a part in fueling discontent.

- In late April and early May, peaceful protests over the land reforms proceeded in various towns and cities without police intervention. In late May, however, the authorities reacted to a second wave of announced demonstrations by preemptively jailing would-be protesters, detaining hundreds of demonstrators nationwide, and ultimately depicting the popular protests as a bid to topple President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Tokhtar Tuleshov, an entrepreneur from southern Kazakhstan, was jailed in November for allegedly masterminding the coup plot. Two prominent civil society campaigners from the city of Atyrau, Maks Bokayev and Talgat Ayan, were detained in May and jailed in November for allegedly fomenting the protests with Tuleshov, even as they maintained that they were exercising their constitutional right to peaceful assembly.

- Some protesters called for the resignation of Nazarbayev at the demonstrations, an indication of how frustrations with his authoritarian rule are growing among some citizens. The faltering economy is fueling social disaffection, although Nazarbayev continues to enjoy genuine popularity among many citizens, who—under the heavy influence of state propaganda—credit him with delivering years of rising living standards, political stability, and relative ethnic harmony. However, the land protests demonstrated that support for the administration may be more fragile than it appears.

- Adding to the atmosphere of tension, in 2016 Kazakhstan experienced two fatal attacks targeting law enforcement structures that suggested homegrown extremism and violent dissent are rising problems. One targeted a military base in the western city of Aktobe in June and left four civilians and three soldiers, as well as 18 suspected attackers, dead. The other in July was by a lone gunman on law enforcement in Almaty, in which eight police officers and two civilians were killed. Astana defined these as acts of terrorism, although the label fails to recognize that the attackers targeted law enforcement structures rather than civilians, suggesting that repressive policies intended to counteract radicalism are generating grudges against the security forces and may be inadvertently fuelling extremism.

- In December, the country marked its 25th anniversary of independence, and its septuagenarian president marked a quarter of a century at the helm of independent Kazakhstan. Despite his previous statements that the country needs to create resilient institutions to withstand an eventual transition of power, the authorities made no moves in 2016 to undertake democratic reforms of the super-presidential political system that would assist in ensuring a stable transition of power. This system creates political risks for the post-Nazarbayev future, since it may fracture when he eventually leaves office.

- The authorities continued, however, to implement, albeit gradually, an ambitious program of public administration reforms known as the “100-step” program. The authorities also continued implementing a promising program to devolve powers to local government and engender greater public involvement in decision-making. In 2016, under the local self-governance program, public councils were set up nationwide to allow public oversight at all levels of local government, which the government intends to be platforms to involve the public in the making of decisions that affect their everyday lives.

- In March, Kazakhstan held a parliamentary election that was marred by serious irregularities and resulted in essentially replicating the outgoing parliament. The legislature is dominated by Nazarbayev’s Nur Otan party, which won 82 percent of the vote; two smaller progovernment parties—Ak Zhol and the Communist People’s Party of Kazakhstan (CPPK)—took the remaining seats. In the period since independence, elections in Kazakhstan have increasingly become stage-managed events designed to shore up the power of Nazarbayev and Nur Otan rather than offer voters a choice about who rules them. This election again emphasized the undemocratic nature of a political system dominated by the president and forces loyal to him to the exclusion of any opposition. At the same time, the authorities, with the advice of western PR companies, continued in 2016 to uphold Kazakhstan on the international stage as a “young” and open-minded country on a gradual trajectory toward democracy.

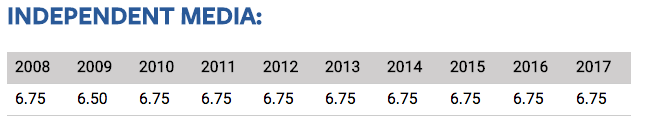

- Pressure on the independent media remained intense in 2016. In October, two prominent journalists, Seitkazy Matayev and his son Aset Matayev, were jailed on corruption charges, following a controversial trial that sparked concerns over political motivations. In May, Guzyal Baydalinova of the independent Nakanune.kz website was jailed for “disseminating false information.” In July, her co-defendant Tair Kaldybayev, an entrepreneur jailed for allegedly paying to place false reporting on the site, was found hanged in prison in a death declared a suicide. Baydalinova’s sentence was commuted to a suspended one in July and she was freed. Her website closed down in April, owing to the difficulties of operating under pressure.

- Corruption remained entrenched in 2016, although there were small-scale efforts to tackle it, notably through the creation in January of Government for Citizens, an online portal and physical offices intended to streamline public services and reduce opportunities for petty bribery. In April, Nurali Aliyev, the president’s grandson, was named in an international expose as the owner of offshore assets, after Nazarbayev had been urging citizens to take advantage of an amnesty on the repatriation of offshore funds and property. This reinforced public perceptions that despite official rhetoric, the powerful enjoy exemptions from anti-corruption campaigns.

- Outlook for 2017: Nazarbayev is likely to remain entrenched in power throughout 2017, and is unlikely to undertake substantial and meaningful reforms to establish the resilient political system featuring checks and balances on presidential rule that he says Kazakhstan requires to withstand a transition of power. Social tensions will continue to rise, creating a growing risk that Nazarbayev will bequeath to his eventual successor intractable problems that will be challenging to resolve under the current system. The land protests of 2016 demonstrated that Nazarbayev’s levels of popularity—while high—are vulnerable to erosion, and disillusionment with his long authoritarian rule may continue to corrode support for the regime in 2017. Astana’s heavy-handed response to the 2016 land protests is likely to act as a deterrent to major public protests, however. The risk of violent attacks, whether inspired by Islamic radicalism or other motives, is rising, and while attackers have previously targeted the security forces, attacks on civilians cannot be ruled out in 2017.

- President Nursultan Nazarbayev has ruled Kazakhstan for a quarter of a century and, despite previously speaking of the need to create a resilient political system capable of withstanding his eventual and inevitable departure, took no steps in 2016 to reform Kazakhstan’s highly centralized political structure. In March, the 76-year-old president—who is known by the official title of Leader of the Nation and enjoys a personal exemption from constitutional presidential term limits—entrenched his power through a parliamentary election, which his ruling party, Nur Otan, won by a landslide. Celebrations of Kazakhstan’s 25th anniversary of independence in December were harnessed to reinforce a burgeoning cult of personality that surrounds the president, by presenting him as the father of the nation who has presided over a quarter of a century of political and economic successes.1

- Kazakhstan’s entire system of governance rests on the executive branch. Nazarbayev and Nur Otan control all institutions of power at the national and local levels, including the parliament, the military, the judiciary, the security apparatus, and even offices that are nominally independent, such as the Central Electoral Commission and the human rights ombudsman’s office. The president appoints and may dismiss the prime minister, who is responsible for executing policies rather than formulating them. The rubber-stamp bicameral legislature, which contains only loyal presidential supporters, can be dissolved by the president at any time under the constitution. With no independent institutions to perform effective checks and balances on power, and no evidence that building such institutions is on the presidential agenda, Kazakhstan remains at risk of a major political crisis when its current president leaves office.

- In 2016, the authorities alleged that Tokhtar Tuleshov, an entrepreneur from southern Kazakhstan, had hatched plans to carry out a coup d’etat by allegedly fomenting nationwide protests against land reforms in April and May in order to seize power.2 This is not the first time the administration has blamed social unrest on an alleged coup plot: in 2011, Astana claimed that fatal riots that spiraled out of a mismanaged oil strike in the western town of Zhanaozen—in which police shot dead 15 civilians—were fomented by the president’s enemies in a bid to topple him.

- Some of the land protesters adopted the slogan “old man out!”, suggesting that while the president remains genuinely popular in many quarters of society, his popularity may be eroding due to the faltering economy and disillusionment with 25 years of his authoritarian rule. In 2016, economic growth slowed for the third consecutive year to stand at 1 percent, owing to low global oil prices and the repercussions of downturns in neighboring Russia and China, both major trading partners.

- In 2016 there was an uptick in violent attacks targeting law enforcement structures, indicating rising disillusionment with the regime among elements of the population susceptible to radicalism. In June, four civilians and three soldiers were killed in an attack by gunmen on a National Guard base in the western oil city of Aktobe; 18 suspected attackers died in the security operation.3 In July, eight police officers and two civilians died when a lone gunman attacked law enforcement structures in Almaty. The attacker said he was avenging what he perceived as persecution of Muslims by the security forces, as well as targeting them because he considered his previous convictions for robbery and weapons possession—over which he had served time in prison—to be unfair.4 These were the first such major violent incidents in Kazakhstan since a spate of attacks targeting security forces in 2011 and 2012.

- The authorities defined the 2016 attacks as acts of terrorism, although this conclusion fails to recognize that the attackers targeted law enforcement structures rather than the civilian population, indicating that they are at least partly inspired by grudges against the security apparatus. The motivations for the violent attacks in 2016 cannot be unequivocally stated to be related to Islamic extremism, and the incidents do not bear the classic hallmarks of terrorist attacks. Nevertheless, the nature of the attacks and the stated motives of the attackers suggest that homegrown extremism is, to some degree, a rising risk for Kazakhstan among disaffected groups, and that repressive policies intended to stem such radicalization may be counterproductive.

- In September, Nazarbayev carried out a major government reshuffle, replacing the long-serving prime minister, Karim Masimov, with Bakhytzhan Sagintayev, the first deputy prime minister.5 Masimov became director of the National Security Committee, indicating that he retains Nazarbayev’s confidence at a time when the intelligence agency’s counterterrorism role assumed greater importance following the Aktobe and Almaty attacks.

- During the reshuffle, Dariga Nazarbayeva, the president’s eldest daughter, lost her position as deputy prime minister—to which she was appointed in 2015—and became a senator in the upper house of parliament. This was a demotion, but the appointment potentially positions Nazarbayeva to assume the constitutionally important role of Senate speaker, who takes the reins of power if the president is incapacitated.6 Nevertheless, the influence of the president’s family on national and local governance was weakened in 2016. His grandson Nurali Aliyev, Nazarbayeva’s son, resigned as deputy mayor of Astana in March, shortly before he was named in an international exposé as the owner of offshore assets.7

- In 2016, the government continued to implement a reform program unveiled in 2015 called “100 Concrete Steps to Implement Five Institutional Reforms”,8 with five goals: creating a transparent, accountable government; professionalizing the civil service; ensuring the rule of law; boosting industrialization and economic growth; and promoting unity in multiethnic Kazakhstan. In January, Nazarbayev announced the creation of a new state body called Government for Citizens9 to boost transparency and streamline public services by acting as a one-stop shop for their provision by the end of 2017.10 If implemented in full, these ambitious reforms might have a positive impact on improving public administration and reducing corruption. However, implementation is gradual, and the impact of the reform program had yet to be felt in any substantive manner in 2016.

- Kazakhstan has not held a parliamentary or presidential election on schedule since 2005. In March, Kazakhstan held snap parliamentary elections that entrenched the political status quo, delivering a rubberstamp parliament identical in terms of party composition to the outgoing lower house. In 2016, the official reason for holding the parliamentary vote a year early was to provide the legislature with a fresh mandate, since it had finished adopting laws to implement the 100-step reform program. However, observers suggested that the real motivation was likely that the administration preferred to install a new legislature for another five years before a possible rise in popular discontent, given the prospect of protracted economic problems facing the country.11 The election offered an opportunity to reaffirm the hierarchy of the ruling party and local authorities’ loyalty to the central government, who were required to demonstrate their capacity for mobilizing voters in support of Nur Otan.

- The ruling Nur Otan party headed by Nazarbayev won a landslide with 82.2 percent of the vote in the March 20 elections. Two other parties won seats in the Mazhilis (lower house): the pro-business Ak Zhol (Bright Path), with 7.18 percent of the vote, and the Communist People’s Party of Kazakhstan (CPPK), with 7.14 percent.12 Ak Zhol and the CPPK are opposition parties in name only: they do not make substantive criticism of the president or government, or attempt to hold the administration to account through the legislature.13 Three of the six parties standing failed to win seats because they did not cross the 7 percent electoral threshold.

- The only party standing in the election with a record as an opposition party was the National Social Democratic Party (NSDP), which offered muted criticism of the administration during the campaign but failed to win any seats.14 No other opposition parties exist in Kazakhstan: in recent years the authorities have closed or co-opted some parties, while others have split due to internal differences, or abandoned their political activities due to intimidation. The Communist Party of Kazakhstan was closed by court order in 2015,15 while Alga! was banned in 2012 and its leader Vladimir Kozlov was jailed on charges of fomenting unrest in the town of Zhanaozen in 2011.16 In 2013, the leader of the Azat party, Bolat Abilov, quit politics, leaving his party moribund.

- International election observers from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) deemed the parliamentary elections “efficiently organized, with some progress noted,” but stated that “Kazakhstan still has a considerable way to go in meeting its OSCE commitments for democratic elections.” It noted that the campaign was low key, stating that “genuine political choice is still lacking,” and calling for reform of a legal framework which “restricts fundamental civil and political rights.”17 The Central Electoral Commission rejected the criticism and pointed out that the OSCE/ODIHR had praised Kazakhstan’s performance on 25 counts, mostly connected to administration of the election.18

- Kazakhstan witnessed the largest and most widespread public protests since independence in spring, as demonstrators took to the streets to voice their peaceful opposition to land reforms. The demonstrators were seeking to overturn reforms that would have expanded the sale of land to private investors, a measure the government deemed vital to boost agricultural investment, but which opponents resisted on the grounds that land is a national asset and should be publicly owned. They also feared that the reforms would open a backdoor route for foreigners to purchase land, which foreigners had been barred from owning. Protesters expressed particular concerns about potential sales of agricultural land to Chinese investors (whom they believed would be the most eager buyers), fueled by sensitivities about Chinese control over other natural resources in Kazakhstan, such as oil. Despite acknowledging grassroots concerns, Astana depicted the protests as a bid to overthrow the state—an indication of its entrenched reluctance to accept the existence of dissent or opposition of any form.

- The protests began in April and culminated in a nationwide day of protest on May 21, on which the authorities cracked down with mass arrests. Ahead of the protest, 40 activists were preemptively detained and jailed for up to 15 days to prevent them from demonstrating. On May 21, hundreds of protesters were detained across Kazakhstan in what human rights campaigners said was a violation of their constitutional right to peaceful protest.19 The authorities justified the detentions on the grounds that the demonstrators were violating Kazakhstan’s stringent laws on public assembly, which require them to apply for permission to rally from the local authorities 10 days in advance. All applications to hold legal demonstrations against the land reforms had been turned down. Most of those detained were released without charge, although rights activists said that there had been violations of their legal rights during their time in custody. Fifty-one people were charged with breaching public assembly laws, with 12 fined, four jailed for up to 15 days, and the others cautioned.20

- In May, Nazarbayev sought to head off public opposition to the sale of land reforms by imposing a moratorium on the changes until the end of 2016,21 which he extended in August to the end of 2021.22 He also created a public commission, which included members of civil society,23 in a sign of willingness to engage in public dialogue that some activists welcomed as positive but belated.

- The authorities claimed that the land protests had been fomented by Tokhtar Tuleshov, an entrepreneur from southern Kazakhstan, who had allegedly taken advantage of the protest mood to stir up unrest in order to seize power. Tuleshov was in jail during the protests, following his arrest on unrelated charges in January. In October, he was put on trial behind closed doors, and in November he was jailed for 21 years.24 Although the case against Tuleshov appeared flimsy, he testified at the trial of Maks Bokayev and Talgat Ayan, two prominent civil society activists in the city of Atyrau tried separately as accomplices, to fomenting the protests from his prison cell.25 Bokayev and Ayan, who were arrested in May, pleaded innocent, arguing that they were exercising their constitutional right to peaceful protest, but were convicted in November. Both were jailed for five years on charges of breaching public assembly laws, inciting social strife, and disseminating false information.26 Human rights activists raised concerns over alleged procedural violations during the trial and suggestions that Bokayev did not have access to appropriate medical treatment.27

- In 2016, several activists were convicted over social media postings under the controversial charge of incitement to ethnic, religious, tribal, or social strife. Civil society campaigners have urged the government to abolish this legislation on the grounds that it is allegedly abused to muzzle critics. In January, two civil society activists were jailed on charges of inciting ethnic discord in their Facebook postings, following a controversial trial that raised freedom of speech concerns.28 Yermek Narymbayev and Serikzhan Mambetalin were jailed for three and two years respectively, but freed shortly afterwards when their prison terms were suspended.29 In July, Zhanat Yesentayev, an activist from northwestern Kazakhstan, was sentenced to two and a half years of restricted freedom over Facebook postings that allegedly incited ethnic enmity ahead of the land protests.30 In December, Igor Chuprina, a resident of northern Kazakhstan, was jailed for five and a half years on charges of inciting ethnic strife and propaganda of separatism over postings made on social media that allegedly argued for parts of Kazakhstan to secede and join Russia.31

- An oil sector strike, which broke out in September in the town of Zhanaozen—where industrial action by oil workers in 2011 culminated in fatal unrest—was rapidly settled after the provincial government mediated.32 This indicated that the violence of 2011 has made the authorities more open to dialogue as a means of preventing escalations of industrial unrest, although they also have at their disposal the controversial provisions of a labor code,33 approved in 2015 in the face of opposition from trade unionists.34

- A new law on funding for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which significantly tightened government control over the operations of civil society groups,35 came into force in 2016. It established a single state operator via which all funding for NGOs must be channeled,36 effectively granting the state a monopoly on deciding which NGOs receive funding and for what types of activity. Pursuant to the legislation, in October burdensome new rules were introduced requiring NGOs to report foreign funding. Under the new rules, NGOs must submit reports of foreign funding with 10 days of signing a contract with a foreign grantee, and must report on their use within 15 days of the end of the quarter in which the contract was signed.37 The introduction of this requirement followed concerns about foreign funding of NGOs raised in Kazakhstan’s media in July.38 In November, the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) highlighted “intrusive inspections by tax authorities” at NGOs, which raised concerns about “intimidation and undue interference” with their activities.39

- In October, Irina Mednikova, a prominent Almaty-based civil society campaigner, was the victim of a mugging that she believed connected to her activism. Money and a hard drive of material intended for the organization of a youth forum in the city of Atyrau were stolen.40

- In August, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit organization defending digital civil liberties, alleged that journalists, lawyers and political activists critical of Kazakhstan’s government had been targeted by an online phishing and malware campaign it alleged was carried out on behalf of Kazakhstan’s government. Many of the targets are party to the government’s litigation to expose hackers who stole its emails.41

- In 2016, the authorities continued to make wide use of a controversial 2009 law on religion, fining and jailing religious group leaders and worshippers found in breach of its stringent requirements,42 raiding places of worship, censoring religious literature, and preventing missionary activity.43 In July, police raided Baptist summer camps in West Kazakhstan Region to check that children were present with parental consent, and fined a woman who took her grandchild to a Baptist church event in Kostanay Region.44 In November, police detained five organizers of a yoga seminar in Almaty under the law, accusing them of distributing illegal religious literature.45

- In September, a new Ministry for Religious Affairs and Civil Society was set up with the official remit of assuring the right to freedom of conscience and managing relations between the government and civil society.46 The new ministry was a response to the Aktobe and Almaty attacks, and combining the two portfolios of civil society and religious affairs is an indication that the government acknowledges the need to use civil society to help combat extremism. The ministry focused early efforts on counterextremism measures, and in October the minister, Nurlan Yermekbayev, identified boosting the secular nature of the state as a priority.47 In October, the government clarified that the wearing of the hijab or any other visible sign of religious identification was not permitted in schools under existing regulations.48

- In June, the United Nations Human Rights Committee expressed concern over Kazakhstan’s “broad formulation” of the concepts of extremism and incitement to religious enmity, and urged it to bring counterterrorism and counterextremism legislation into compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.49 In December, Nazarbayev signed into law new legislation intended to counteract terrorism and extremism.50 The amendments tightened up control over internal migration, weapons circulation, and communications. Human rights campaigners expressed concern that the new measures were intimidating to the general public, and would affect law-abiding citizens rather than potential extremists.51

- In August, there was an intercommunal clash between the Kazakh and Tajik communities in South Kazakhstan Region. Three people were injured, and homes and cars were burned, after rumors—later proved unfounded—surfaced of the sexual abuse of a Kazakh child. Like a previous clash between the two communities in 2015,52 it revealed hidden ethnic tensions that the government refuses to acknowledge. The administration promotes ethnic unity as a core value, by and large successfully, but discussion of ethnic tensions is taboo, and the authorities seek to prevent open debate on the issue.

- In January, a new law on access to information, adopted in 2015 in a move welcomed by civil society campaigners, came into force.53 The aim of the law is to force officials to place information of public interest in the public domain. The legislation prohibits state bodies from concealing information on a number of designated public interest topics, and obliges officials to hold regular public meetings to report on their activities, which they are now doing. In May, the government said that official websites were falling short of fully meeting the requirements of the law, on average distributing information in 38 categories as opposed to the 52 required by law (74 percent).54 The government made no moves to proceed with plans announced in 2015 to compel Internet users to install a national security certificate on their devices that would allow the state to access, monitor and edit https-encrypted traffic.55

- However, despite these modest steps, the media environment in Kazakhstan remains tightly controlled. In October, the government revealed plans to regulate the status of bloggers, under planned amendments to legislation governing the spheres of information and communication to be put before parliament in 2017.56 Bloggers expressed concern that the move would restrict their freedom of speech by subjecting them to the same rules as journalists; the government maintained that it would grant them greater rights.

- In 2016, the authorities continued using court orders to block websites and social media accused of hosting “extremist” content. In July, the authorities said that 94 sites were being blocked.57 Amendments to the communications law introduced in 2014 allowed the authorities to block websites or shut off social networks without a court order, on the grounds that they contain terrorist or extremist content, or calls to participate in “mass unrest.”58 In August, the website www.change.org became inaccessible after a petition was posted on it calling for the resignation of Karim Masimov, then prime minister;59 it remained blocked at year’s end. In December, some social media outlets became periodically inaccessible shortly after users began circulating a media interview given by Mukhtar Ablyazov, a businessman wanted by Kazakhstan, following his release from detention in France. The government explained this as a “technical glitch”.60

- In 2016, journalists encountered obstacles in exercising their professional duties, particularly covering public protests. In May, 55 reporters were detained while attempting to report on the land protests; most were later released without charge.61 In October, two prominent Kazakhstani journalists were jailed on corruption charges following a trial that sparked concerns over political motivations. Seitkazy Matayev, head of the National Press Club and president of the Union of Journalists, and his son Aset Matayev, head of the KazTAGnews agency, were sentenced to six and five years in jail respectively.62 The Matayevs—who were accused of embezzling government media subsidies—alleged in court that the charges were trumped up to seize their valuable assets and muzzle independent voices. Seitkazy Matayev named Nurlan Nigmatullin, speaker of the lower house of parliament, and media magnate Aleksandr Klebanov as the instigators of the case, an accusation they denied.

- In November, Bigeldi Gabdullina, the editor-in-chief of the Central Asia Monitor website and the director of Radio Tochka, was arrested on corruption charges. Gabdullina was accused of extorting officials by promising to cease critical reportage of their activities in his media outlets if they favorably allocated government media subsidies.63 He was still in detention awaiting trial at year’s end.

- In May, journalist Guzyal Baydalinova was jailed for 18 months on the charge of “disseminating false information” (known as the “rumor spreading law”).64 She worked for the independent website Nakanune.kz, established by former journalists from the Respublikanewspaper, which was closed in a crackdown on independent media in 2012. Baydalinova and entrepreneur Tair Kaldybayev were convicted in a case, filed by Kazkommertsbank, concerning a report on corruption in Almaty’s construction industry; Baydalinova had already been convicted on libel charges in 2015 relating to this article.65 The court found that Kaldybayev had paid to plant false reports on Nakanune.kz and on Respublika.kz-info, a Russia-based website carrying material critical of Kazakhstan’s government. In July, Baydalinova’s sentence was suspended and she was released,66 shortly after Kaldybayev—who was also jailed—committed suicide in prison.67 In September, Irina Petrushova, the editor of Respublika.kz-info, announced that she was closing the site and ending the Respublika media project that she launched in 2000, owing to technical and financial problems, and issues connected to the political situation in Kazakhstan.68

- In March, Nakanune.kz journalist Yuliya Kozlova was acquitted on charges of possession of narcotics that investigators said they found during a raid related to Baydalinova’s case, which she said were planted.69

- In July, the newspaper Tribuna/Ashyk Alan—one of Kazakhstan’s last independent publications—was ordered to pay $15,000 in damages in a libel case brought by a former Almaty city hall official, Sultanbek Syzdykov. The publication had deemed Syzdykov corrupt after he was accused of embezzling $70,000 from public funds; a criminal investigation was closed after he repaid the sum.70 In October, the Uralskaya Nedelya newspaper was ordered to pay $10,000 in libel damages to a police officer for reporting on an apology made to the newspaper’s editor, Tamara Yeslyamova. The paper reported that the officer offered Yeslyamova an apology after she was detained and fined for covering land reform protests in May; although the newspaper presented an audio recording as evidence, the officer denied that he apologized.71 Media loyal to the government engaged in a smear campaign against the land protesters in spring, dubbing them agents provocateurs and traitors financed by foreign interests intent on fomenting revolution in Kazakhstan.72

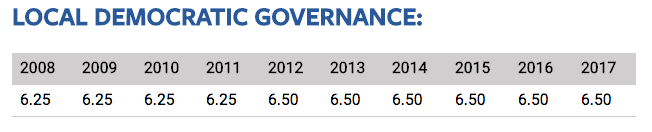

- In 2016, the government continued to implement the second stage of its 2013-2020 local governance strategy; as part of the strategy, Astana is handing greater governing and financial powers to local government.73 The second stage of the strategy began in 2015, when the government adopted new rules on local government financing;74 and a legislative reform package75 intended to grant local authorities greater financial powers and increase the involvement of local populations in the decision-making process.76 In September, Nazarbayev made it clear that local self-governance remains a major priority for his administration.77

- In January, a law obliging local authorities to establish public councils to allow public oversight at all levels of local government came into force.78 In May, the authorities reported that the process of forming public councils was complete.79 In September, the government reported that 225 public councils had been set up—12 at the national level, 16 at the regional level, and 197 at the town and district level—containing 3,791 members, 30 percent of whom were women.80 Under the law, at least three quarters of members must be representatives of civil society or the general public, so as to avoid monopolization of discussions by officials. In September, teething problems—including cases of public officials breaching regulations by chairing councils—emerged, which the authorities pledged to stamp out.81 With Nur Otan leading the public council initiative, and having drafted the law on its creation, some civil society campaigners have expressed concern that voices loyal to the authorities will dominate council meetings to the exclusion of others. The government says that the councils are intended to be genuine platforms for public involvement in decision-making that affects their everyday lives.

- The local self-governance package includes measures specifying the way public local assemblies are to discuss how financing should be organized. They also include measures to boost public involvement in monitoring the use of budget funds; measures to grant akims(mayors) greater budgetary decision-making and fundraising powers; and measures placing revenues from certain fines and taxes—including small business tax and taxes on local government property—in the hands of local government. Local community assemblies now have input into deciding on how budget funds should be used, and are obliged to conduct monitoring of their use every six months to boost transparency and accountability. From 2018, smaller towns and villages will start to draft their own budgets, and from 2020 this scheme will be rolled out nationally.82

- In a reflection of the high priority the government attaches to the local self-governance program, Nazarbayev took a personal interest in the effectiveness of the new local tax-raising measures. In September, he quizzed a village mayor on how much funding had been raised under the new rules, how it had been spent, and how the expenditure decision had been decided by local consensus.83

- Local governments continued to roll out hotlines to improve citizens’ access to communication with officials, using social media as well as websites and telephone lines.84 Such hotlines are popular with the public for making local authorities more responsive to their needs and problems.

- Despite these efforts to boost local self-governance, the system remains highly centralized. The mayors of all major cities and governors of Kazakhstan’s 14 regions are presidential appointees, with no accountability to the communities they serve. In smaller towns and villages, mayors were elected via indirect suffrage in 2013, but—although the authorities touted these first ever mayoral elections in Kazakhstan as a major step towards democratization—the elections have to date not demonstrably increased the independence or democratic accountability of local government. Mayoral elections took place in towns and villages inhabited by only 45 percent of Kazakhstan’s total population, and all candidates were elected by maslihats (local councils), which are overwhelmingly dominated by Nur Otan.85

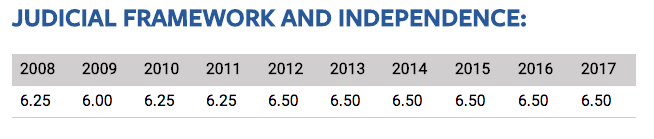

- Kazakhstan’s constitution recognizes the separation of powers and safeguards the independence of the judiciary, but in practice the courts are subservient to the executive and protect the interests of the ruling elite. The president appoints judges to the Supreme Court and local courts, as well as members of the Supreme Judicial Council. The courts regularly convict public figures brought to trial on politically motivated charges, often without credible evidence or proper procedures.

- In June, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) welcomed several measures taken in recent years related to the judicial framework and penitentiary system. These measures include an expansion of the number of restraint measures stopping short of deprivation of liberty; the establishment in 2015 of an obligation under the Criminal and Criminal Procedure Codes to register and investigate all allegations of torture; and the establishment of a juvenile court system and a decrease in the rate of children “in conflict with the law.”86

- In November, a court sentenced Ruslan Kulekbayev, who was convicted of carrying out the Almaty shootings in July, to death; this was the first death sentence handed down in Kazakhstan since 2006.87 A moratorium on the implementation of the death penalty has been in force since 2004, and all those facing capital punishment—31 people—had their sentences commuted to life in jail in 2007.88 In June, Nazarbayev said that those who carried out the Aktobe attack deserved to face the death penalty, and throughout the second half of 2016 there were public calls from various officials to establish the death penalty for acts of terrorism.89 UNHRC urged the government not to act on these calls in June. UNHRC also expressed concern that, despite the moratorium, the Criminal and Criminal Procedural Codes maintained capital punishment for 17 types of crimes, and urged the government to consider further restricting it.90

- In 2016, the government continued to take measures as part of its campaign to humanize the judicial and penitentiary systems under its 100-step reform program. Changes included plans to reform the probation system to improve the integration of ex-prisoners into society,91 and an ethical code for judges, adopted in November, which was designed to establish improved standards of professional behavior and ethical standards.92

- In August, Vladimir Kozlov, an opposition leader, was paroled after serving four-and-a-half years of his seven-and-a-half year sentence.93 Kozlov was controversially convicted in 2012 on charges of fomenting social unrest that spiraled out of an oil strike in Zhanaozen in 2011. Twenty-one oil workers and townspeople who served prison sentences over the violence had previously been freed.

- In March, the human rights watchdog Amnesty International accused the authorities of “failing in their duty” to investigate reports of torture by law enforcement agents and prison warders.94 It welcomed legal reforms, including extending the mandate of special prosecutors to investigating torture allegations, but said they had failed to address “systematic gaps and failures.” The authorities do occasionally act on reports of abuse in places of detention, usually by prosecuting a few junior officers. In October, a prison guard was jailed for nine years for raping and torturing a female prisoner.95 In November, the interior minister replaced the entire management of the Penal Enforcement System Committee, although it was not specified whether this was in response to that high profile rape case.96 In July, officials said 23 prison officers had been jailed on torture charges over the last eight years.97 Two police officers were jailed in Kostanay Region in November for torturing a confession out of a suspect.98 In September, reports of abuse outside places of detention surfaced when villagers in Pavlodar Region accused police of using disproportionate force while attempting to prevent illegal fishing.99

- Systemic corruption thrives in Kazakhstan on the country’s oil and mineral wealth. Elites, who often enjoy immunity from prosecution or investigation, use their positions to appropriate, control, and distribute key resources for personal gain. Along with law enforcement bodies, the Agency for Civil Service Affairs and Counteracting Corruption is the main body tasked with dealing with corruption, but it is part of a civil service in which graft is entrenched and vested interests thwart efforts to eradicate it. In 2016, the government proceeded with measures unveiled in 2015 under the 100-step reform program to root out graft and nepotism from the civil service and the judiciary.100 In January, the government issued a resolution ordering the creation of “Government for Citizens”, a one-stop shop to streamline public services and boost transparency. It is also intended to reduce opportunities for bribery within the civil service.101

- Despite a warning by Nazarbayev in 2015 that there were “no untouchables” in Kazakhstan when it comes to corruption,102 perceptions persisted that anticorruption efforts are typically political and economic tools that allow some officials to accrue power while intimidating or constraining their rivals. There are frequent prosecutions on bribery and corruption charges, but high-level officials are rarely targets; when they are, their trials often take place amid suspicions of political motivations.

- In November, senior managers at a subsidiary of the Bayterek development fund, which channels investment for the government’s industrialisation and economic diversification strategy, were arrested on suspicion of bribe-taking in a case that highlighted that corruption remains rife in state-run institutions.103

- In April, Nurali Aliyev, the president’s eldest grandson, was named in an international expose as the owner of offshore assets,104 as Nazarbayev continued to urge citizens to take advantage of an amnesty on the repatriation of offshore assets running until the end of 2016.

- The authorities have relentlessly pursued former senior officials and businessmen who have fled abroad, typically only issuing arrest warrants after the targets have fallen afoul of the regime for political reasons. This sends a clear message of deterrence to other potential dissenters who may consider seeking sanctuary abroad. In 2016, Kazakhstan continued to seek the extradition from France of oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov to face fraud charges.105 In December, a French court blocked106 an order signed by the French government in 2015 to extradite Ablyazov to Russia, and ordered his immediate release on the grounds that the extradition request was politically motivated.107 Campaigners had urged France not to extradite him to any ally of Kazakhstan that might send him on to his home country, and said he risked ill-treatment and the denial of his right to a fair trial in Kazakhstan because of his record of political opposition to Nazarbayev.108 Ablyazov, who has denied the charges against him and said they were politically motivated, was barred from fighting a fraud case brought against him by a Kazakh bank in the London High Court after he fled the UK to escape a prison sentence for contempt of court in 2012. He was arrested in France in 2013, and remained in detention until his release in December.

- Almaty city hall continued to pursue Viktor Khrapunov, a former mayor, through the US courts over allegations he embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars in public assets.109 Kazakhstan issued an Interpol arrest warrant for Khrapunov and his wife in 2012, after he began publicly criticizing Nazarbayev, and the US corruption case was opened in 2014, a decade after Khrapunov left the post of mayor and six years after he emigrated from Kazakhstan to Switzerland.110

- High-profile corruption cases in 2016 suggested that graft remained rife at a high level. In June, Talgat Yermegiyayev, who was in charge of organizing the prestigious EXPO-17 exhibition to be held in Astana in 2017, was sentenced to 14 years in jail for embezzling millions of dollars in state funding for the event.111

- Two European corruption investigations involving Kazakhstan were ongoing at year’s end. In February, a French probe into suspected kickbacks paid over a 2013 lucrative helicopter deal112 was expanded amid suggestions reported by a French media outlet that Airbus allegedly paid Karim Masimov, the then prime minister, 12 million euros to secure the contract.113 In July, the United Kingdom’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) secured extra government funding114 to continue an inquiry into the mining acquisitions of Kazakhstan’s ERG (formerly ENRC) natural resources company.115 Since 2015, the probe has only targeted ERG’s operations in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and not those in Kazakhstan.116

Author: Joanna Lillis is a freelance journalist specializing in Central Asian affairs who has been based in Kazakhstan since 2005.

Freedomhouse.org, 2017