Amid talk over the leadership, the country has to solve fundamental problems

Early one Sunday morning in June, a group of young men seized rifles from two gun shops in Aktobe, a city in the steppe of north-western Kazakhstan, and began a series of deadly attacks that would shake the country. Over the next few days, they hijacked a bus, assaulted an army unit, seized hostages and engaged in shoot-outs with police that left 25 dead.

The outbreak of homegrown terrorism jolted this central Asian nation of more than 120 ethnic groups, known for its relative tolerance. For the Kazakh government, concerns about security joined a growing list of political, economic and social threats that could undo one of the most impressive success stories in the former Soviet states.

“We are alarmed about the risk of Islamic radicalism,” says Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, chairman of the senate in the capital Astana. “[The attacks] were a wake-up call for us.”

Since its founding 25 years ago out of the ashes of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan’s economy has grown 10-fold thanks to its oil riches. Central Asia’s “big brother” has been a haven of stability and prosperity in a region plagued by Islamist radicalism, poverty and drug trafficking.

Most Kazakhs credit one man with this success: Nursultan Nazarbayev, the 76-year-old president. A former Communist party boss, Mr Nazarbayev navigated post-Soviet independence from 1991. He threw the doors open to foreign investors, privatised key parts of the economy and created a westernised elite by sending tens of thousands of young men and women to study in Europe and the US. He is also credited with forging a national identity in a country where forced migration in the Soviet era had made the traditionally nomadic Kazakhs a minority in their own homeland.

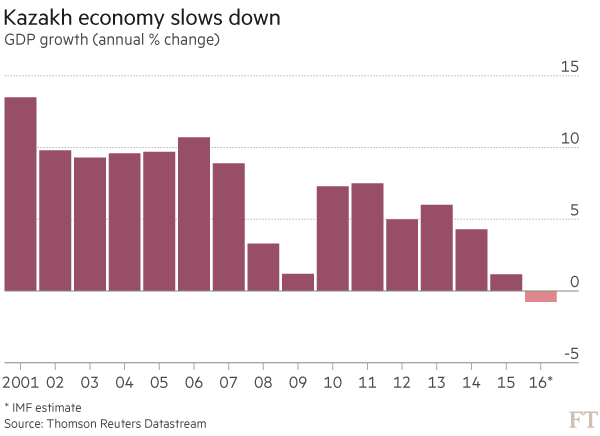

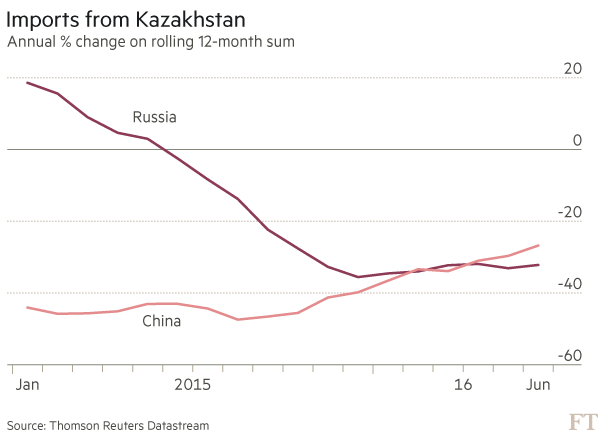

Kazakhstan has benefited enormously from its founding father’s pragmatic economic policies and geopolitical savvy, but the question of succession looms large. Over the past two years, Kazakhstan has been battling the fall in oil prices, a recession in Russia and a slowdown in China. And while it has managed to avoid a recession, it has seen strikes at its oilfields and protests over planned land reforms this year.

“This is the moment when you need a real risk manager. Right now there is no real successor to deal with such a dangerous situation,” says Aidan Karibzhanov, general director of Visor Holding, an Almaty-headquartered investment house with assets across Central Asia.

‘100 concrete steps’

In Almaty, the former capital, a modern city with bright offices in glass and steel skyscrapers, western-educated executives admit that the uncertainty over who will replace Mr Nazarbayev is their top concern — and the economy’s biggest risk.

One attempt to reduce the threat of a disorderly transfer of power is a much-touted initiative named the “100 concrete steps”. Launched by Mr Nazarbayev in May 2015, it lists 100 measures aimed at building the rule of law, improving the civil service, ensuring economic growth, boosting national unity and making the state more accountable. One of the items on the to-do list: consult civil society on every piece of draft legislation.

“This is the main idea: to have a strong and stable political situation that is bigger than one person,” says Timur Kulibayev, a powerful oligarch and the president’s son-in-law.

Falls in the oil price and the tenge, the Kazakh currency, have added to the problems for Kazakhstan's economy © Getty Images; Dreamstime

The president’s slogan has long been “the economy first, politics later”. Aktoty Aitzhanova, head of the National Analytical Centre, a think-tank at Nazarbayev University based in Astana, says the 100 steps initiative marked a shift. “If you want to build a strong, sustainable state, you need to move beyond the policy of economic reform,” she says.

But critics say the effort is failing to change a deeply paternalistic political culture — the other half of Mr Nazarbayev’s legacy. “In an era of deteriorating socio-economic conditions and reduced state support, little incentive exists in this vertical power system to overhaul Kazakh institutions that are inherently opaque, highly personalised and governed by informal practice,” says Kate Mallinson, an independent political risk analyst for Central Asia.

Mr Tokayev confirms that the appetite for political change is limited. “We still believe that the president must be powerful because in this very troublesome volatile region, parliamentary systems do not work,” he says.

Parliament’s consultation with non-governmental organisations on draft legislation remains a hollow exercise. “The problem is that we are discussing draft bills that have already been agreed by the government, so we are just discussing some articles, not the concept,” says Yevgeny Zhovtis, director of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law. “Our suggestions are rarely ever embraced, and we see legislation becoming ever more repressive.”

One case in point is the reaction to the Aktobe attacks. The government is setting up a ministry for religious and civil society affairs, and parliament is planning laws to monitor terrorist risks more closely. Mr Zhovtis fears the changes will broaden the security services’ powers while failing to address the economic causes for radicalisation.

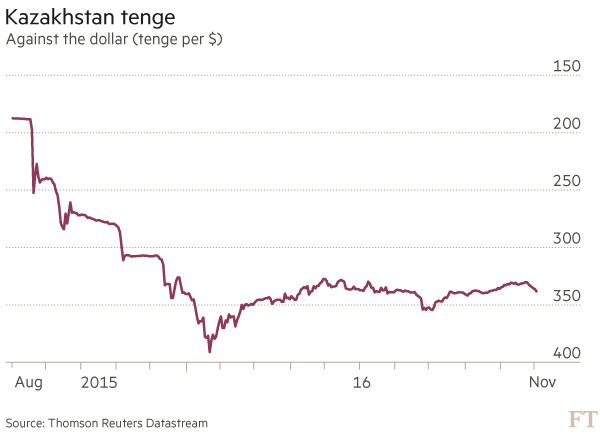

This spring, public outrage erupted in protests against legislation to offer foreign investors longer leases of agricultural land. The plan was aimed at developing agriculture, a sector seen as vital in reducing the country’s heavy dependence on oil at a time of low commodity prices. But the changes infuriated ordinary people who struggled to repay dollar-denominated mortgages after the steep devaluation of the tenge, the local currency.

After scores of people were detained, the policy was dropped. Still, two prominent activists who participated in the protests are now on trial for “inciting social and national discord”.

‘Powerful neighbours’

Mr Nazarbayev remains popular. “When we gained independence in 1991 we were like a homeless child. We had nobody to look after us,” says Kenges Rakishev, chairman of Kazkommertsbank, the country’s largest lender by assets. “We could have been like begging on the streets.”

Many also applaud Mr Nazarbayev for his skill in balancing the interests of the country’s neighbours. The size of western Europe, Kazakhstan lies sandwiched between Russia to the north and China to the east, betwixt its former imperialist ruler and a colossal, fast-growing economy with dreams of regional dominance.

Political manoeuvres: the president moved his daughter, Dariga Nazarbayeva, to the senate and former PM Karim Massimov to the security services © Getty Images

“These very powerful neighbours were given to us by God,” says Nurlan Nigmatulin, chairman of the lower house of parliament and a former aide of Mr Nazarbayev. “We must turn that into an advantage. It will be the foundation for our economy.”

It is a high-wire act. Kazakhstan wants to benefit from Beijing’s initiatives to revive the ancient Silk Road with economic corridors to Europe. Kazakhstan expects China to invest $26bn between 2016 and 2021 in the country both in infrastructure and industry, in conjunction with liberalising bilateral trade. And yet Kazakhstan has chosen western oil majors as partners in exploiting its biggest and most promising deposits.

In private, some officials do not conceal their reservations towards Russia. “The west is where we are looking, that’s what we want to become,” says one lawmaker. “In my opinion, what Russia is doing in Syria can be called war crimes.”

But the country knows it cannot afford to turn against Moscow. “Dealing with Russia is like a boxing fight. If you hold them close, you are less likely to get hit,” says Mr Karibzhanov.

Kazakhstan is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, a pet project of Russian President Vladimir Putin. But its open door policies have powered economic exchanges with the EU, which now accounts for one-third of its foreign trade.

Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014 raised fears across the former Soviet republics that Moscow might seek to redraw other borders in the region by force. In response, Mr Nazarbayev has voiced support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity without overtly condemning Mr Putin. In general, Kazakhs look at western sanctions against Moscow and cite Nietzsche’s maxim: what does not kill you makes you stronger.

Mr Nazarbayev has been adept at protecting Kazakhstan’s independence and will be a hard act to follow. “There was a succession plan two or three years ago,” Mr Karibzhanov says. “Then the Crimea and Ukraine story changed the plans.”

A dynastic move?

At the heart of the risks to Kazakhstan’s stability lies the economic crisis that resulted from the fallout of three financial shocks in quick succession. On the heels of the 2014 decline in oil prices, a sharp contraction in Chinese growth and a recession in Russia eroded demand and investment from its two most important trade partners.

Nominal gross domestic product shrank by a quarter in dollar terms between 2013 and 2015, the tenge crashed and inflation soared. This year, real incomes dropped for the first time since 1999 and the government expects GDP to increase 0.1 per cent, the slowest pace in 17 years.

The start of production and expansion plans at some of the country’s big oilfields have raised hopes of recovery. In July, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Lukoil agreed to a $37bn investment in the Tengiz field, in which they own stakes, to increase output by almost 50 per cent by 2022. But oil prices will need to rise before the country feels the benefits. Oil at $50-$55 a barrel “means not more than 1 per cent GDP growth”, says Mr Kulibayev.

In a sign of concern, Mr Nazarbayev reshuffled the government in September. He moved his daughter Dariga from the deputy prime minister’s post to the senate, and made Karim Massimov, the former prime minister and political heavyweight believed to be a rival of the president’s daughter, head of the security services.

Since the head of the senate is the constitutional successor to the president, Mr Nazarbayev could be only one step short of having a dynastic succession in place.

He may, however, be watching how the succession unfolds in neighbouring Uzbekistan. After Islam Karimov, the Uzbek president who was only two years Mr Nazarbayev’s senior, died in August, it was not the senate chairman, the constitutional successor, who was named acting president but Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the former prime minister. He needs to be confirmed in an election next month.

For all its undoubted progress, Kazakhstan’s future will depend on more than just picking the next strongman — or woman.

“It can’t be just Nazarbayev 2.0, just the question of what person will take over, like in Uzbekistan,” says Mr Zhovtis. “There has to be a new political configuration, something more collective. If they manage to get this in place over the next two to three years while he’s still here, we will be lucky.”