Campaigners drawing attention to the Xinjiang detentions say Nur-Sultan’s public relations campaign is two-faced.

Campaigners drawing attention to the Xinjiang detentions say Nur-Sultan’s public relations campaign is two-faced.

Try as it might, Kazakhstan cannot shake its Xinjiang headache.

On one hand, it needs to temper domestic fury stoked by Nur-Sultan’s perceived failure to give succor to ethnic Kazakhs caught up in anti-Muslim internment campaigns in China’s far-flung western regions.

Doing so, however, risks enraging officials in China, a vital economic partner for Kazakhstan.

Kazakh Foreign Minister Beibut Atamkulov emerged from cover last month by adopting the boldest official position to date over the situation in Xinjiang.

Eschewing the terminology favored by Beijing, which euphemistically refers to its interment facilities as vocational training centers, Atamkulov spoke in parliament on March 5 about “camps.” He said his ministry was working on around 1,000 cases involving ethnic Kazakhs that had been brought to the attention of authorities by relatives.

“Unfortunately, this pressure is directed not only toward Kazakhs,” Atamkulov said in another remark obliquely confirming the scale of the crackdown.

According to some independent assessments, up to 1.5 million Muslims in Xinjiang have fallen prey to the internment campaign. The purpose of this crackdown is said to be to inculcate deeper patriotic sentiments and to pressure internees into shedding their Islamic identities. The majority of those that have been detained are believed to be ethnic Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and Hui.

Atamkulov’s willingness to raise the matter in parliament is testament to the effectiveness of activist movements representing the 200,000 Chinese-born Kazakhs repatriated under the government’s Oralman program.

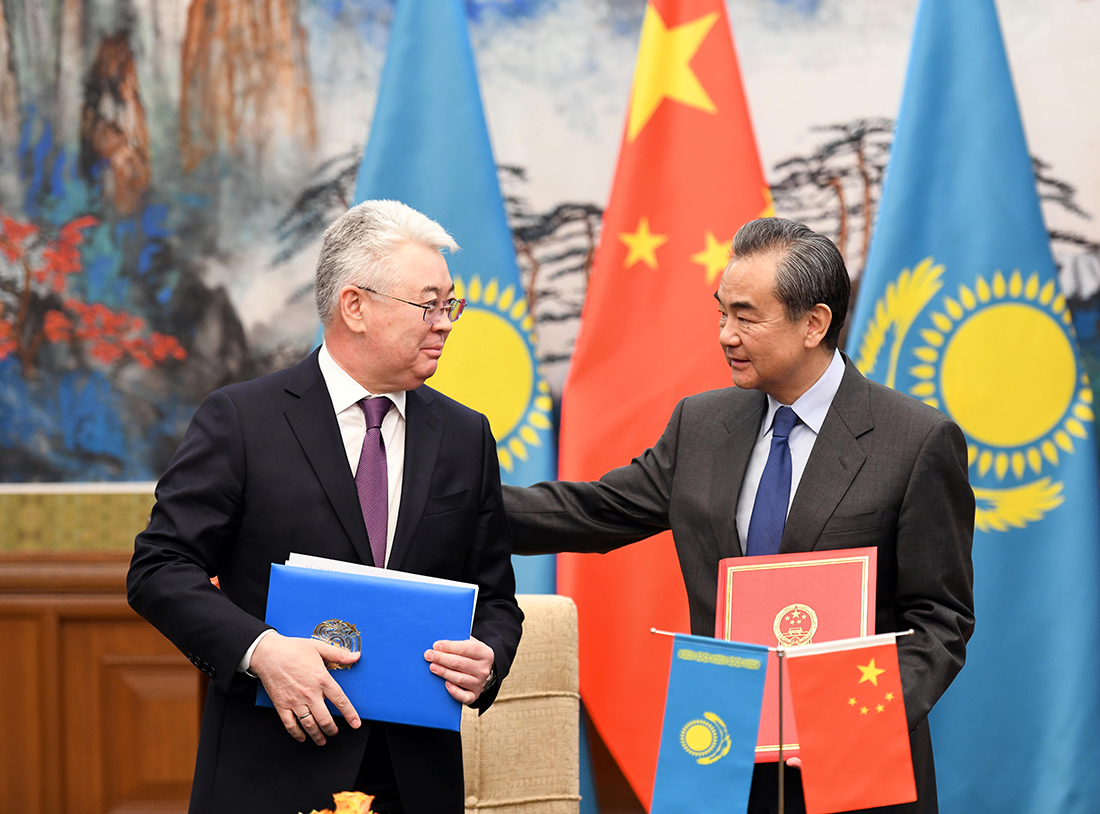

His boldness had seemingly diminished, however, when he met Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on March 28 in Beijing.

In a statement, China’s Foreign Ministry quoted Atamkulov as saying that Kazakhstan “understands and supports the measures taken by China's Xinjiang region to crack down on three evil forces" – Beijing’s boilerplate shorthand for terrorism, separatism and religious extremism.

The media reports that followed, which took the statement at face value as an expression of Kazakh support for Chinese policies in Xinjiang, caused consternation in Nur-Sultan.

The Foreign Ministry dashed off a clarificatory note urging the media “to correctly convey statements, not to distort, not to replace concepts, and not to take phrases out of context, especially on matters sensitive to the population.”

Ethnic Kazakhs living in China “were an important factor in friendly relations” between Beijing and Nur-Sultan, the ministry added.

Campaigners who have been at forefront of drawing attention to the Xinjiang issue call this an exercise in two-faced public relations.

“There are some good people in government that are trying to do what they can for our Kazakhs in China,” said Omirkhan Altyn, a Kazakh based in Germany, who in 2017 raised the Xinjiang crackdown at the Fifth World Kurultai of Kazakhs, a diaspora event attended by then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev.

“But it’s not enough," Altyn told Eurasianet. "The Chinese lobby is very strong here. Their money swims around, facilitating our local corruption.”

Kazakhstan is not the only country caught floundering in the face of the Xinjiang conundrum.

According to Human Rights Watch, the 57 members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation faced concerted lobbying from Beijing not to mention Xinjiang at a ministerial conference last month.

That was a shift of stance from December, when the OIC voiced concerns over developments in the region. A March 2 resolution from the IOC, which includes Kazakhstan among its members, instead commended China on its treatment of Muslim citizens.

Nur-Sultan’s handling of the Xinjiang question inside Kazakhstan has been just as clumsy.

Atajurt volunteers Gulzhan Toktaysn, left, and Shynar Kylysheva at the group's Almaty office. (Chris Rickleton)

Last year, authorities dodged considerable outcry when a judge ruled to free Sayragul Sauytbay, a woman who was facing prosecution for illegally crossing into Kazakhstan from China to join her family.

Sauytbay’s court testimony about a camp where around 2,500 Kazakhs were interned proved an effective clarion call for politically engaged nationalists.

When she was released, it helped go some way to defusing tensions.

Since then, however, Sauytbay has been refused permanent asylum – a status that Nur-Sultan appears to worry could be interpreted as an affront by Beijing. Sauytbay said she has been pressured by the security services to drop her asylum bid, but she has persisted undeterred.

Her lawyer, Aiman Umarova, is taking a confrontational approach with authorities.

“I have told these [officials]: ‘Your relationship with China is your business. Securing this woman’s right to live with her family as a citizen is mine,’” Umarova told Eurasianet.

Sauytbay’s next appeal is due on April 8.

Umarova also represents Serikjan Bilash, a vocal Xinjiang campaigner who has garnered much popularity for his defense of Sauytbay and countless other ethnic Kazakhs in trouble.

Bilash is currently under house arrest in Nur-Sultan pending investigations into alleged incitement of interethnic hatred.

Prosecutors are basing their allegations on what some are describing as the fanciful interpretation of a speech that Bilash delivered in February. In the speech, Bilash called for a “jihad” against China and its Xinjiang policies, before going on to qualify this campaign as an explicitly non-violent initiative.

When state television aired the speech, days after Bilash’s March 10 arrest, it omitted the passage in which the activist made it clear he did not intend his words to be understood as an exhortation to bloodshed.

Ever since Bilash’s arrest, hundreds of his supporters have filmed video appeals demanding his release. Bilash has released his own audio statement complaining of directives from authorities to part ways with his lawyer.

While authorities may – for now – have succeeded in muffling one of China’s most vitriolic critics, they remain uncertain over what to do with the Atajurt movement he helped create.

The Almaty premises of Atajurt, which has collated a vast trove of testimonies from relatives of Xinjiang detainees, were ransacked and sealed off by police on March 10.

Less than a month later, on April 2, the group announced that the police had once again given them access to their own offices.

“We got the key from them," Atajurt volunteer Kairat Baitola told Eurasianet. "We are ready to work again.”

Chris Rickleton is a journalist based in Almaty.

Original article: EURASIANET