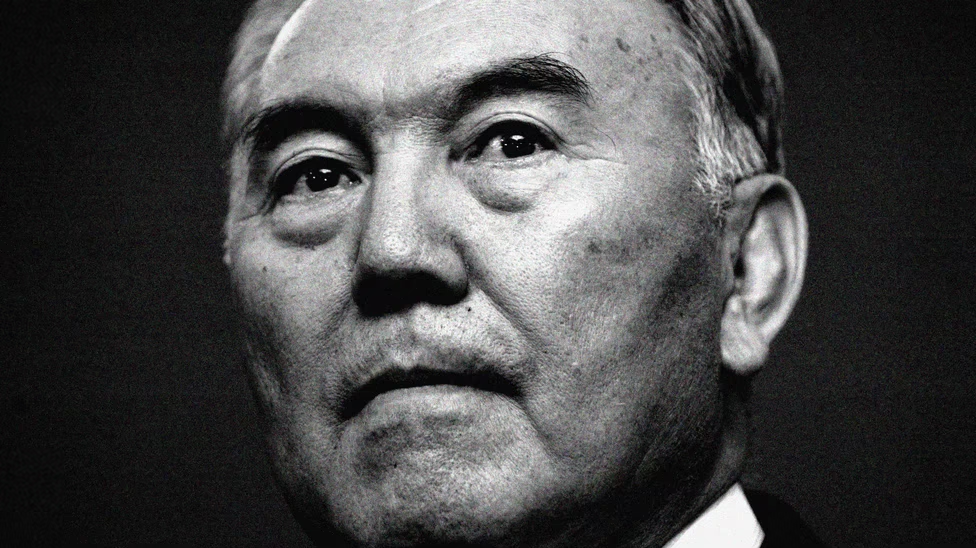

Nursultan Nazarbayev has enough oil to make himself into anything he wants.

Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of Kazakhstan, is a man of grand projects—and the grandest of them all is Astana, his new capital city. Once an obscure fortress town of the Russian Empire, in a region where temperatures swing from 100°s in the summer to -40°s in the winter, Astana today is a fast-growing metropolis of 600,000—and a showcase for a staggering variety of public works. Billions of dollars are being poured into the construction of government buildings, museums, monuments, religious shrines, entertainment palaces, apartment blocks, and hospitals. Business barons and foreign governments, aware of Kazakhstan's growing importance as a global oil exporter, are courting Nazarbayev with generous contributions to Astana's development. To cite just a few examples: the Persian Gulf state of Qatar has funded a national Islamic center, with a mosque able to accommodate 7,000 worshippers; a Saudi prince's foundation has funded a center for cardiac surgery; and the Russian-Jewish oligarch Alexander Mashkevich, who has large metal holdings in Kazakhstan, has funded the Beit Rachel synagogue and Jewish center. Everyone, after all, is aware of the city's immense importance to Nazarbayev. "The heart of the nation now beats here," he informed his people in 1999, two years after officially uprooting the government from Almaty, its former seat, in the temperate south of the country.

Nazarbayev claims to be the planner of Astana's every detail, right down to the choice of yellow and white paints for the houses. There is no reason to doubt his obsession. On the ground floor of the presidential palace is an eye-catching scale model of the emerging capital. The model highlights the so-called "new city," on the left bank of the Ishim River. Important architects, including Lord Norman Foster, of London, are working on major commissions (Foster is building a glass-pyramid "Palace of Peace"), but Nazarbayev has made his own role in designing Astana clear. "I'm the architect," he once told a reporter, "and I am not ashamed to say that."

Considerable speculation attends the reasoning behind the move to Astana. Some Nazarbayev watchers say the main idea was to distance the seat of power from China, whose vast population inspires fear among the Kazakhs. Others say it was to establish the capital in an area populated by many ethnic Russians and close to the Russian border—thus checking any notions those citizens might have about breaking away to unite with Russia. My own hypothesis, born of several days' wandering around the place recently, is that Nazarbayev thinks of the city as a blank canvas.

No small measure of personal vanity attaches to this endeavor. Consider, for example, the Baiterek, an abstract-looking monument in the center of town. Designed to represent a tree of life planted in the heart of Eurasia, the monument has become the principal symbol of the new capital and the new country. A 1,000-ton trunk of white metal shoots up 344 feet from the ground and branches into limbs enmeshing a golden 300-ton glass ball seventy-two feet in diameter. Visitors can take an elevator to the top of the monument and into the ball, which affords a 360-degree panorama of the city's gleaming new structures (the massive, blue-domed presidential palace among them), vacant lots reserved for new buildings, and the steppe beyond. A plaque there is inscribed with wishes for world peace from the Chinese Taoist Association, the Muslim World League, and the Russian Orthodox Church, among other faith groups. But the main attraction is a silver mold of Nazarbayev's palm print. Placing a hand in it strikes up the Kazakh national anthem. Or at least it's supposed to. I tried but couldn't raise a note—a problem that, I was told, a visiting Gerhard Schröder had also had. At night the monument is lit up by pulsating mauve and turquoise lights.

The Baiterek seems right out of Architecture for Dictators 101—and there's no denying that Nazarbayev is a dictator, albeit of the soft variety. He has benefited from a regime-manufactured cult of personality since he became president, in 1991, when Kazakhstan achieved its independence. Not surprisingly, both corruption and cronyism abound. That so many around the world are humoring his grandiosity is owing mainly to the country's impressive deposits of oil, which began to be developed intensively after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Western analysts are confident that the country will soon become one of the world's top oil exporters. "It is the real deal when it comes to oil," a senior U.S. diplomat in Kazakhstan told me.

"He thinks he is the Messiah," Zharmakhan Tuyakbay told me about Nazarbayev. Tuyakbay is one of the leaders of an elite opposition faction made up of Nazarbayev's former close associates, which aims to topple the regime, establish a Western-style parliamentary democracy, and, if popular support exists, return the capital to Almaty. (Most opposition leaders still live in Almaty or abroad, and detest Astana.) As for oil, the opposition hopes that it will be the president's undoing. James Giffen, a U.S. citizen and a consultant to the Kazakh regime, is awaiting trial in New York on federal charges of funneling more than $84 million in kickbacks to three senior Kazakh officials, two of whom were subsequently named by prosecutors as Nazarbayev and the former prime minister Nurlan Balgimbaev. The indictment alleges that this money—which came from the purchase of Kazakhstani oil rights by certain Western oil companies in the 1990s—belongs to the government and people of Kazakhstan. The indictment also details the alleged transfer of funds into various Swiss bank accounts and alleges that millions of dollars were used to buy luxury items, including diamond jewelry. Opposition leaders are gearing up to use the Internet and all other available channels to publicize what they refer to, in PR-savvy style, as "Kazakh-gate."

A soft-spoken man in his late fifties, with a full head of steel-wool hair and a wardrobe of dark business suits, Tuyakbay impressed me as level-headed and resolute when we met for lunch at the Tabard Inn, in Washington, D.C. "The structure of power," he told me, "is totally corrupt."

Tuyakbay had come to town to attend a dinner of the International Republican Institute, a pro-democracy group chaired by Senator John McCain. McCain detests autocrats like Nazarbayev, as I learned when we discussed Kazakhstan. "Would I be glad if he were gone?" McCain said. "Yes." Later he elaborated on that thought. America, he said, "cannot support despotic governments and expect over time not to pay a heavy price." Kazakhstan's oil is no reason, he feels, to embrace the current regime. Bush has been reluctant to publicly criticize Nazarbayev's authoritarian bent—especially in light of Nazarbayev's commitment to ship oil by a Washington-favored pipeline route that skirts Russia and ends on the Turkish Mediterranean. But in a speech at the dinner Tuyakbay attended, Bush did sound a note of encouragement for the Kazakh opposition. "Across the Caucasus and Central Asia," he declared, "hope is stirring at the prospect of change—and change will come."

Perhaps it will: a Washington-applauded putsch recently removed the authoritarian leader of Kyrgyzstan, a neighbor of Kazakhstan and another former Soviet republic. The spark in Kazakhstan could come as soon as December, when Nazarbayev may be elected to another seven-year term—in a contest that is unlikely to be "free and fair."

What I discovered during my journey to Kazakhstan, however, is that the prospect of change has many ordinary folks there feeling nervous. I went in search of a despised dictator and instead found a tolerated one—in some quarters even a popular one.

Kazakhstan lies in the great Asian steppe. Its 15 million people are scattered across an expanse of territory as large as Western Europe, stretching from China in the east to the Caspian Sea in the west. By tradition the Kazakhs, a Turkic-Mongol people, are nomads, grouped in kinship clans and larger hordes. Islam arrived in the eighth century, but except in the less nomadic south it never inspired an especially fervent devotion. European culture and the Russian language (now universally spoken) came with the Russian colonial conquest, starting in the eighteenth century. Early in the Soviet period the Kazakhs endured a brutal series of Moscow-dictated transformations, including the collectivization of agriculture. Many Kazakhs, unwilling to become settled farmers, let their cattle perish. But they gradually accommodated themselves to Soviet rule and developed their own strong bench of party leaders.

Nazarbayev accepted and mastered the Soviet system. The son of ethnic Kazakh shepherds, he was born in July of 1940, in a village in southeastern Kazakhstan, close to the border with Kyrgyzstan. After high school he joined tens of thousands of other rabochiye—manual workers conscripted by the Communist Party's economic planners—at an enormous steelworks in the republic's northern town of Temirtau. He began at the bottom, as an iron caster, gulping salt water to retain body fluids in the furnacelike conditions. He joined Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, and proved adept at cultivating powerful patrons. By the time he left the area, in 1980, for a senior Party job in Almaty, he was well along the path to the top Party post of first secretary (reporting directly to Moscow), which he attained in 1989.

Some of his current rivals, educated at Moscow academies in economics or engineering (or trained by the KGB), look down on Nazarbayev as crude and ignorant. They maintain that the public would be scandalized to know of his private antics. One opposition source, who told me that Nazarbayev is a binge drinker, claims to have seen him put away a quart and a half of vodka in a single day in the 1990s, but also admits, "I never saw him lose control." (Nazarbayev's personal physician told me the president's health is "very good.") Other opposition sources, in service of their point, supplied me with snapshots of Nazarbayev at a private party in Turkey in the mid-1990s, hosted by a Turkish construction magnate. In one of them Nazarbayev, attired in a white leisure suit, is tucking a wad of money into the brassiere strap of a belly dancer. In another he is handling a golden pistol—a gift, apparently, from the host.

To explain Nazarbayev's rise to the top, critics use the Russian word hitryi, which translates roughly as "tricky" or "cunning"—as in a fox. Stalin, too, was said to possess this trait. Even nonpartisans admit that Nazarbayev has a helpful, possibly instinctive plasticity. Nursultan Nazarbayev, a coffee-table book of photographs lovingly compiled by his press office, includes a reproduction of a painted Soviet-realist-style portrait that depicts him in a muslin blouse with sleeves rolled up, a sheaf of wheat on his lap. Another reproduced painting suggests a kind of modern Khan: he is shown in a suit and tie astride a black horse, a robe draped over his shoulders. Nazarbayev, nominally a Muslim, has made the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, in a nod to Islamic sensibilities, but his chosen image for Western consumption is that of an economic modernizer. To perfect that image he has sought advice from Michael Porter, a famous economic-development guru at the Harvard Business School. Porter flew to Kazakhstan last January for a three-hour lunch with Nazarbayev, punctuated by vodka toasts. "He really wants his country to be a success in a market economy," Porter told me, "and bristles at being compared with other leaders in the region." In the 1990s, because of Nazarbayev's unremitting urging that his citizens make their own way on entrepreneurial initiative, Kazakhs nicknamed their leader "Bazaar-bayev."

In mid-June, a few days after arriving in Kazakhstan, I paid a visit to Temirtau, where Nazarbayev had worked as a youth. A yellowish, foul-smelling exhaust poured from the chimney stacks of the steelworks, which is now privately owned by Mittal, an international steel conglomerate. From the townspeople I learned of Temirtau's rough introduction to capitalist culture. The plant, which during peak Soviet times employed some 40,000 people, is down to a work force of about 25,000. The health of the workers, I was told, had declined with the end of the Soviet practice of sending rabochiye to special state-owned sanatoria for needed rest. Pollution from the plant was poisoning the water and spoiling the breast milk of new mothers. And because Kazakhstan has difficulty controlling its borders, Temirtau had become a transit point for smugglers moving narcotics along a route between the poppy fields of Afghanistan and the drug markets of Europe.

It all sounded dreadful. And yet the people of Temirtau seemed to blame not the Nazarbayev regime but the sudden and chaotic collapse of the Soviet system. Lyudmila Kurtavtseva, an environmental activist, told me that things were actually at their worst in 1996 and 1997; since then government initiatives to address pollution and other hazards have gradually improved living conditions. Outside the gates of the steelworks I chatted with Alex (he declined to give his last name), a twenty-five-year-old blond, blue-eyed Russian who grew up in Temirtau and now earns about $150 a month as a mechanic at the works. His salary is not enough to live on, but Alex, who lives alone, gets financial help from his family. He folded a pair of well-muscled forearms across his bib overalls; his hands were caked with black soot. "Maybe Nazarbayev is one of the richest people in the world," Alex said, "but he cares about the people and does things for the country."

For reasons I could not pin down, it is said in Kazakhstan that Nazarbayev is the planet's tenth wealthiest man. If the state is rich with oil, people reason, then the head of state must be rich too.

Those sentiments were echoed on a visit to Chimkent, the main city in the impoverished rural region of southern Kazakhstan, from which Zharmakhan Tuyakbay hails. In the old quarter I met with Ziyatulla Madaliyev and Abdugani Baibulotov, a pair of Uzbek elders, at a modest private home shaded by an arbor of grapevines. Uzbeks have lived in Chimkent for centuries (present-day Uzbekistan is just a short drive away), and make up about 30 percent of the current population. They are also pillars of the local business establishment. Madaliyev poured out bowls of hot tea, and we nibbled from trays of candies, nuts, and dried apricots. I turned the conversation to politics. "We would prefer for Nazarbayev to stay for another seven years—in fact, for as long as he is living," Madaliyev told me. "If there is a new president, he will not stop stealing until his pockets are full." This was an idea I heard repeatedly: Nazarbayev and his cronies are already so wealthy that their appetite for money has been sated.

It seemed plain that the opposition's call for Western-style political reforms was not a burning issue for these people. If their political liberties were restricted, others remained untrammeled. Baibulotov told me that he goes to the neighborhood mosque every Friday. The mosque is 300 years old, he said, and has survived the Bolshevik Revolution and all other onslaughts. And these days, he said, it is thriving; 80 percent of the people there on Fridays are young men. In neighboring Uzbekistan a more repressive ruler, Islam Karimov, enforces tight restrictions on religious activity and consequently faces a grassroots revolt urged by Islamic militants. Life is better here in Kazakhstan, the elders told me.

For a decidedly unofficial view of Nazarbayev, I made secret arrangements to meet Galymzhan Zhakiyanov, Kazakhstan's most famous political prisoner. With the help of an opposition activist living outside Kazakhstan, I met up in Astana with Zhakiyanov's son, Berik, for a drive to the Shiderty prison colony, two hours east of the capital. A student at the University of Texas in Austin, Berik had rented a cottage near the prison gates in order to spend summer time with his father as prison rules permitted. My subterfuge was necessary because Zhakiyanov had not asked the authorities for permission to give an interview, fearing that it wouldn't be granted.

As we drove out on the highway toward Shiderty in a Toyota Camry, the white seedling strands of the kovyl' steppe grass suggested a carpet of snow. Cowboys on small chestnut horses tended cattle. Eventually the Toyota veered left at a grove of white birch trees and sped past a coal mine. Berik told me to duck down. We halted at his cottage, and I was hustled through the door into a room decorated in the fashion of a yurt, the felt tent traditionally used by Kazakh nomads. The floor and walls were covered by carpets, and in the middle was a low round table.

In walked Zhakiyanov, a slight man wearing eyeglasses, a sports shirt, and blue jeans. An ethnic Kazakh born in 1963, Zhakiyanov was an up-and-coming provincial governor in the early years of Kazakhstan's independence but was dismissed after helping found Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan, a reform-oriented group that criticized state power as excessively centralized—and demanded an explanation of Nazarbayev's holdings in foreign bank accounts. A criminal investigation was conducted of Zhakiyanov's alleged misdeeds as governor, and in 2002 a court handed down a seven-year sentence for "abuse of office" and related financial crimes. "The real reason for his imprisonment," Amnesty International states in its most recent report on Kazakhstan, "appeared to be his peaceful opposition activities."

The Shiderty colony is located in prime Soviet-gulag territory: Solzhenitsyn did time at a camp in the area in the 1950s. But Zhakiyanov acknowledged that Shiderty, a low-security center, is not a great hardship. He works at a horse farm, milking mares to produce kumys, a fermented beverage much enjoyed by Kazakhs.

A cook set on the table a steaming platter of besbarmak, a Kazakh national dish of lamb chunks boiled in broth and ladled over large, flat squares of pasta. It was delicious. We sipped tea from bowls as we sat, in a concession to me, on small chairs instead of on the carpet. I shifted the discussion to Nazarbayev. "Yes, he has a good survival instinct," Zhakiyanov said, "but he doesn't have any strategic plan. He can't see further than his own nose. If he was thinking strategically, he would be doing political reforms."

Zhakiyanov was poring over the Federalist Papers, on his son's recommendation. "The danger in Kazakhstan is instability of the political system," he said. He set an empty plate on the table and stacked three apples. He gave the plate a little shake, and the apples toppled. That's Nazarbayev's "vertikal' vlasti," he said—his top-down hierarchy of power. He then rearranged the apples, putting a big one in the middle of the plate and ringing it with several smaller ones. He shook the plate again, and nothing moved. This is how it should be, he said: a president in the middle, surrounded by members of a genuine parliament. "Our opposition is not one person but one idea," he said. "No more vertikal' vlasti." So Zhakiyanov and other opposition leaders pledge to amend the country's constitution to limit the president to a single term in office.

"There is no question this transformation will happen," Zhakiyanov said. "The question is how peacefully it occurs."

The week after my interview with Zhakiyanov, I encountered President Nazarbayev at a dinner in Almaty that he gave to open a business conference in town sponsored by the New York—based Asia Society. The tables were laid with platters of smoked fish and bowls of black caviar; white-gloved waitresses poured vodka into small goblets. Richard Holbrooke, a veteran U.S. diplomat and the chairman of the Asia Society, was seated directly across from Nazarbayev. Holbrooke motioned toward him and suggested I go over and introduce myself.

This conversation, I sensed, would be short. Deciding not to mention my unauthorized visit with Zhakiyanov, I told Nazarbayev about my lunch with Zharmakhan Tuyakbay in Washington. Mr. President, I said, the opposition is saying that you have been in power too long, and that the time has come to go. Nazarbayev fastened his large brown eyes on me. "Did you know," he asked, "that Mr. Tuyakbay was the general prosecutor during Soviet times, and he jailed many dissidents?" He shifted his gaze to someone else who wanted to talk to him. I had in effect been dismissed.

Nazarbayev was in his element, surrounded by his closest backers. I chatted briefly with one of the head-table guests, Alexander Mashkevich, the funder of the Beit Rachel synagogue, who holds the title of president of the Jewish Congress of Kazakhstan. Opposition leaders have him in their sights: his holdings in Kazakhstan are sure to be scrutinized avidly if Nazarbayev falls from power. But Mashkevich is viewed as a crucial ally by the country's Jewish leaders, who are struggling to rebuild their community. "We like his good relationship with the government," Yeshaya Cohen, a rabbi at Beit Rachel, told me. Cohen met Mashkevich back in the 1990s, when, he said, he found the businessman stuffing $50 bills into the charity box of a synagogue in Almaty. Another contribution, an envelope stuffed with $50,000 in cash, followed. Beit Rachel itself cost Mashkevich about $2.5 million, Cohen told me.

In an interview at the presidential palace in Astana, Makhmud Kasymbekov, a top Nazarbayev aide, dismissed the opposition leaders' vow to end the system of crony politics in Kazakhstan. "Just get them a tasty pie and a good position," he said, "like mayor of a city, and they will forget about all their opposition views."

And yet surely the palace must be anxious. The list of Nazarbayev's once trusted associates who are now out of office and openly in opposition includes, in addition to Tuyakbay and Zhakiyanov, a former prime minister, a former minister of emergency situations, a former central-bank chief, and a former ambassador to Moscow. In Almaty a former counterintelligence official for the regime told me that Nazarbayev could not count on the loyalty of the security services. The loyalties of others in the political and business elites are also up for grabs; I know of one prominent businessman who is simultaneously encouraging the opposition and courting the regime. The opposition is amply funded by sources that include the former prime minister, Akezhan Kazhegeldin, who made a fortune in the waning days of the Soviet Union by exporting pharmaceutical chemicals to the West at prices of up to twenty times his costs. Kazhegeldin lives a moneyed if restless life in Europe, skipping from capital to capital. "Sometimes at night I dream I am back at the center of things," he told me when I met him recently.

I had a long talk about the situation with Dariga Nazarbayeva, the president's oldest daughter, who has founded a national television channel and is herself active in politics. We chatted at a café at the Ankara, a five-star hotel in Almaty. Nursing a sore throat, she sipped from a cup of green tea into which she deposited spoonfuls of honey. She was smartly dressed in an orange-and-turquoise blazer over a turquoise jersey and white slacks.

A Kazakh newspaper had recently reported that Nazarbayeva believed a putsch against the president, like the one in Kyrgyzstan, was possible in Kazakhstan. I asked her to elaborate. "This is possible everywhere now," she said—not because of grassroots discontent with her father but because Western-aided NGOs and small elites with money and the help of modern media technologies can create a kind of false revolutionary situation. "We have to be more active to avoid this," she said. To that end her father is crafting laws to restrict the activities in Kazakhstan of the International Republican Institute and other Western pro-democracy groups.

Nazarbayeva portrays herself as a political progressive. She conceded that "some people around my father don't want to see power devolved" and that this stance is in the long run an obstacle to "political modernization." As for the criticism that the president's family had in effect hijacked the national economy: "It's a lie." (Nazarbayev himself has dismissed the charges against the consultant James Giffen as "baseless," and denies any personal role in that scandal.)

I gained from her a sharp impression of just how personal and intimate elite politics is in Kazakhstan. Everyone knows everyone else; her children are close friends with the children of a leading opposition figure. She switched from English to Russian to deliver her most emotive points and concluded our talk with a wail against Tuyakbay and his brethren: "Pochemu, pochemu, oni begayut v Washington?" ("Why, why, do they run to Washington?")

Dariga Nazarbayeva is probably right about one thing. If the revolution comes to Kazakhstan, it will be a revolution of the elite, masterminded by Western-oriented activists—some more scrupulous than others—with tight ties to power brokers in Washington, the imperial capital. Such an upheaval might well turn out to be a step forward for global democracy. Still, it is a curious kind of democratic movement that has as its mainspring not "the people" but a selected clique. I gave my estimation of the popular mood to one opposition activist. "Since when," he said, "have the people of Kazakhstan decided anything?"

At issue in vulnerable places like Kazakhstan—for the first time in centuries, the protagonist of its own history—is a question of power. Who gets to write the next chapter of the tale, and the one after that?

In his resolve to remain the story's author, Nazarbayev attends to the public in the way he knows best. Soon after the coup in Kyrgyzstan he announced a 32 percent wage hike for government workers. At the new cardiac center in Astana, the most modern of its kind in Central Asia, more than 650 people have received open-heart surgery. And for the plebeians in his model capital city Nazarbayev is delivering not just bread—and health care—but circuses, too.

Early on a Friday evening I crowded into a stadium with thousands of others for a celebration of the capital's eighth birthday. Hoofbeats sounded the entry of stallions, astride which young men in crimson costumes performed daredevil stunts. Scores of comely young women resplendent in folk garb marched in. There were jugglers and elephants—and a small boy who managed to walk upside down on his hands for at least fifty yards. Halfway through the ceremonies the performers turned and faced Nazarbayev, who was seated in a box in the middle of the grandstand. They took up a chant:

"Astana, Kazakhstan, Nursultan, our homeland!"

Nazarbayev stood and waved. And the crowd roared.

Original source of article: www.theatlantic.com