If Astana and Tashkent can tackle long-term obstacles to growth, there’s great potential in the region.

If Astana and Tashkent can tackle long-term obstacles to growth, there’s great potential in the region.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have come to an interesting point in their histories, looking at major changes of their economies. As the two most important economies in Central Asia, both countries have attracted comparatively significant amount of foreign investment since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, although Kazakhstan had clearly outperformed Uzbekistan in terms of foreign direct investment. During the 2000s the Uzbek economy received less than one-sixth of the $10 billion invested annually in the Kazakh economy.

Kazakhstan began to attract massive investment from international oil majors in the late 1980s. These reserves had been deliberately neglected by the Soviet Union in favor of easier-to-access reserves in western Siberia and elsewhere, and their development led to a unprecedented economic boom in Central Asia. Large-scale investment in the adjacent construction, real estate, and industrial sectors followed, and production of coal, nickel, and other minerals also skyrocketed. While Kazakhstan is only nominally a democracy, it is widely considered to be one of the most open and competitive of the Central Asian economies. Kazakhstan was among the first countries of the former Soviet Union states to conduct fundamental economic reforms. For example, its banking sector during the early 2000s was considered by many observers to be the most advanced in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The fortunes of Uzbekistan were almost inversely proportional to those of Kazakhstan after the breakup of the Soviet Union. The late Uzbek President Islam Karimov was primarily concerned with stability and did not initiate any major economic reforms. While food processing and distribution and textiles were liberalized, the state’s continued control of the financial sector prevented that sector from attracting notable foreign investment. Unlike in the Kazakh financial market, foreign investment has not become the main source of financing for local companies. Amid an economic crisis in the 2000s, Karimov further tightened the state’s grip over the economy, launching, for example, largely politically-motivated attacks on wealthy entrepreneurs, many of whom were forced to flee the country. These measures proved to be counterproductive and soon backfired, resulting in stagnation in Uzbekistan.

Changing of the Guard in Uzbekistan

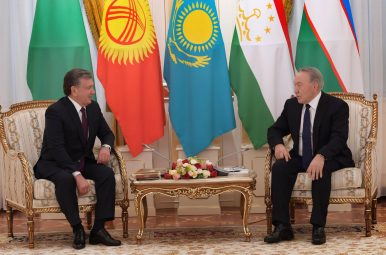

This picture has changed following the death of Karimov in 2016. His replacement, a longtime prime minister and ally of Karimov, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, made waves in December 2016 when he announced that he would remove barriers to investment in the Uzbek economy and work to assuage fears relating to corruption and human rights, which characterized the Karimov administration.

In September 2017, Mirziyoyev made good on his promise and removed currency exchange restrictions, which hindered investors from moving their capital outside the country. These were widely considered to be the primary obstacle to investment in the Uzbek economy, albeit not the only one. Since late 2017, the government has been working on a new tax code in cooperation with several international organizations including the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Mirziyoyev has also taken steps to better the image of the country on a regional and global level. The president, for example, has eliminated a visa requirement for Tajik citizens. On a global level, Uzbekistan has pledged to eliminate the use of forced labor in cotton production. An integral part of this process will be the already ongoing privatization of cotton-producing land, an initiative supported by the World Bank, the International Labor Organization, and several European governments.

Uzbekistan’s economy remained unreformed and underinvested for more than a decade. Undoubtedly, Mirziyoyev has a long reform road before him, where he certainly would witness successes and failures. His track record to date is positive; he has shown himself to be a committed reformer and a president who is determined to transform Uzbekistan’s economy into a market economy. The transformation would certainly offer significant opportunities for foreign investors.

New Opportunities in Kazakhstan?

Much has already been written about the growth of the Kazakh economy during the past 25 years. This is largely attributable to the country’s willingness to reform several of its key industries, welcome foreign investment from Europe and the United States, and, at times, promote comparatively high standards of transparency and corporate governance. Some large state-owned or private Kazakh companies have even conducted IPOs internationally.

But enthusiasm surrounding Kazakhstan has dampened some in recent years. A substantial part of this can be explained by the 2014-2017 slump in global commodities prices and the failure of the Kazakh government to deliver on its privatization plans. The government has kept postponing such plans since 2014. However, the government’s commitment to diversify the economy, the introduction of new subsoil legislation, and other steps may present some opportunity.

The diversification of the Kazakh economy has been discussed since the country first began to produce oil and natural gas in the 1990s. There is significant cause for this: the country has immense amounts of arable and pasture land suitable for agriculture and livestock; ideal conditions for both wind and solar energy; and some of the largest reserves of minerals in the world. In each of these areas, the government has taken steps to promote diversification and there has been no shortage of positive, supporting rhetoric.

Realities of the Road Forward

The economies of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan both stand to benefit if their goals are even partially realized. The attainability of these goals will depend not only on the introduction of reforms and a stated desire to collaborate with credible advisors, but also on the willingness of the countries’ governments to tackle questions which have long stifled their growth.

In Kazakhstan, some of the greatest opportunities — the privatization of its most valuable companies, the modernization of its mining sector, and the diversification of the economy — are also some of the areas most susceptible to corruption and cronyism. For privatization to draw and keep the attention of international investors, clear guidelines that set out the rules of the game (as well as how and where they will be enforced), are required.

Room for preferential treatment for figures close to the administration to carve out segments of the economy before their competitors will need to be eliminated. The same questions apply to the mining sector. While several international mining companies have expressed support for the initiative, it is unlikely that many of them will launch or expand operations in Kazakhstan without greater certainty related to local content or human capital requirements.

For industries at the core of the Kazakh government’s diversification initiative, like renewable energy, the pro-diversification national government must standardize policy and procedure in the less populous regions where renewable potential is greatest. Streamlining the process and increasing the quality of human capital in these regions will lead to more efficient negotiations and licensing processes and reduce if not eliminate frequent complaints about corruption and asymmetries in policy between Astana and more rural areas of Kazakhstan.

In Uzbekistan, opportunity is palpable and optimism high, but as the government begins to implement its reform agenda, there will likely be disagreements and conflicts when the optimism of the future runs into the entrenched interests and realities of the past. To maximize the effectiveness of the reform program, the government will be obliged to find a way through, rather than around, these interests, negotiating compromises in some areas and refusing to compromise in others.

In mining, to take one example, the Uzbek government will likely be faced with the challenge of balancing the interests of historically prominent political partners in Russia and China, with pressure from European and U.S. companies who have in the past been unwilling or unable to be involved in the sector. The Uzbek government’s commitment (or lack thereof) to both confronting entrenched interests and implementing reforms that may be unpopular to these interests and, at times, to the general population, will be closely watched by potential investors in its economy.

Eric Wheeler and Alexey Yugai work for The Risk Advisory Group, a global risk management consultancy headquartered in London. They are based in Moscow.

The Diplomat, May 24, 2018