Russian President Vladimir Putin may be running for reelection as an independent candidate, at least officially — but his electoral campaign is wholly funded by the ruling United Russia party and 22 affiliated foundations. They have contributed the entire 400 million rubles (US$ 7 million) that any candidate can legally spend on the election.

Russian President Vladimir Putin may be running for reelection as an independent candidate, at least officially — but his electoral campaign is wholly funded by the ruling United Russia party and 22 affiliated foundations. They have contributed the entire 400 million rubles (US$ 7 million) that any candidate can legally spend on the election.

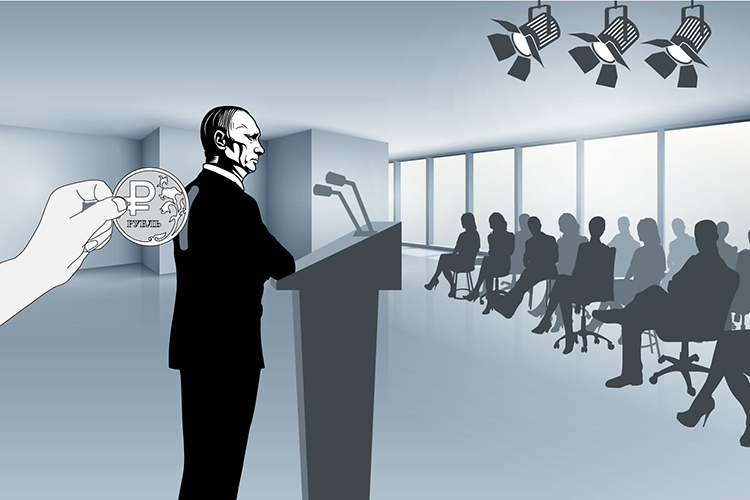

Vladimir Putin is running as an independent candidate in Russia's presidential elections — but donations to his campaign link back to familiar faces from the Russian elite, including those from the country's ruling United Russia party. Photo by: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

This is the first time Putin’s election has been funded in this way. When he last ran for reelection in 2012, a significant portion of the funds were provided by businesses and private individuals.

The actual source of the foundations’ funding is not clear — so the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) decided to try to find out who was behind them.

Reporters found a number of insiders, including Gennady Timchenko, one of the country’s wealthiest businessmen; relatives of Andrey Vorobyev, governor of the Moscow region; and Irina Shoigu, the wife of the minister of defense. Furthermore, some of the foundations have, in the recent past, received support from the state and from state-controlled companies.

The approach is a novel way to finance a presidential race.

“It’s a headache, since the scheme isn’t transparent. Before we were able to at least see and legally identify those individuals who were officially and directly contributing funds to Putin’s electoral campaign,” said Stanislav Andreychuk, coordinator of Golos, a movement that protects voters’ rights. “Now, thanks to these foundations, we don’t even know who stands behind these … donations.”

Indeed, the foundations have not revealed who sponsors them, and they don’t like to talk about themselves. Reporters were not able to find a single website with any financial accounting. And attempts to find out more by telephone twice ended with the same demand — to end the conversation.

“There’s no website. All the accounting can be found at the ministry of justice and tax inspectorate. We’re not a public company,” snapped one representative of a foundation located at United Russia’s Moscow address. “Let’s end this discussion. Anyway, your calls are getting a little exhausting.”

“Independent” Foundations

The central foundation behind Putin’s reelection campaign is the National Foundation for the Support of Regional Cooperation and Development (NFPR in Russian). It is the founder of 20 regional foundations, all using similar names, which contributed to the pre-electoral race.

Many of these are registered at the addresses of regional United Russia party offices, and until 2015 all of them — including the NFPR — used the words “United Russia Party Support Foundation” in their names.

Oleg Polozov is the NFPR’s president. Portraits of President Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev hang in his Moscow office at 3 Banniy Alley — which he shares with United Russia’s Central Executive Committee.

Nevertheless, Polozov assured OCCRP that the foundations are independent of the political party, and that though they were founded in the early 2000s to provide it with financial support, it exercises no direct control over them.

After 2014, a legal change meant that the foundations were no longer able to collect money for the party directly. But they could support its social projects — planting trees, holding sporting events and so on, said Polozov. He isn’t himself a member of United Russia, but said that he “sympathizes with its projects.”

So how did these foundations become the sole sponsors of Putin’s presidential campaign?

“There was no order from on high about it. The initiative came from the foundations themselves. As the saying goes, the early bird gets the worm,” said Polozov. “We got together, discussed everything, and in a few days got all the money together for a special pre-election account [for Putin] with Sberbank.”

A person who worked for the United Russia party confirmed to OCCRP that there had been no official order for the foundations to play such a role. Nevertheless, the source said, their initiative was discussed informally at the highest political levels and there appear to have been no objections.

None of the foundations are public and transparent about their finances. Though they are legally required to publish their reports on an annual basis, they have yet to do so.

“Is that necessary?” asked Polozov in response to questions about the foundations’ transparency.

“In many traditions it’s not acceptable to shout from every corner that you’re doing a good deed. Furthermore, there are different organizational cultures. In one of them, one needs ... publicity to attract sponsors. In the other, the circle of sponsors has already formed, and it’s no longer necessary to advertise oneself. If the goals and tasks of the foundation are being realized, then why does it need a website?” said Polozov.

The NFPR and its associated foundations were founded in the early 2000s, around the same time that the United Russia party itself was formed. When reporters investigated their registration documents, they found that some of them, including the NFPR, shared their Moscow address and telephone number with businesses connected to prominent officials, their relatives, and people known to the president.

This use of the shared telephone number, which appeared in the foundations’ registration documents as recently as January 2018, is unusual, experts pointed out, except in cases when a general number for a building, accountants’, or lawyers’ office is used. That is not the case here, however.

“This could be one of several signs that these organizations are connected with one other,” confirms Alexander Zakharov, a former Russian tax ministry assistant and partner of Paragon Advice Group.

Fishy Relations

One of the connected firms is the Russian Fish Company, once a major fish supplier in the Russian market. The company was once owned by Andrey Vorobyev, the current governor of the Moscow Region and an old acquaintance of one of the founders of United Russia — Minister of Defense Sergey Shoigu. Vorobyev’s father had worked with Shoigu for many years.

In early 2000, Andrey Vorobyev left the business to begin a career in politics, first becoming an advisor to Shoigu during the latter’s brief tenure as deputy prime minister. Vorobyev then headed the United Russia Support Foundation (the NFPR’s name before 2015).

After Vorobyev’s transition to politics, he transferred the seafood company to his brother Maxim, according to Forbes. As the publication reported, the company’s fortunes grew alongside Vorobyev’s political successes in the 2000s. This was when the Russian Fish Company, which later became a subsidiary of the Russian Sea Group, became one of the leading suppliers of salmon, mackerel, trout, herring, and smelt to the Russian market.

In 2011, Maxim Vorobyev found a new, powerful partner — Gennady Timchenko, a friend of the president, became a co-owner in the seafood business.

Neither Andrey Vorobyev nor Russian Aquaculture (formerly Russian Sea Group) responded to questions about connections between the fishing company and the foundations. The Russian Fish Company claimed to have no ties to political activities, nor could it provide information on the shared telephone number.

The Ministry of Emergency Investments

The seafood business is not the only connection between the foundations, Timchenko, and Vorobyev. Some of the foundations own businesses themselves — and these were connected to the same men.

According to the Russian company register, the NFPR once owned a significant share (60 percent) of a firm called Arleya Palatium, also originally registered at United Russia’s address in Moscow. Judging by telephone directories, Arleya Palatium used the same telephone number as the party foundation and the fish company.

Among Arleya Palatium’s owners was an offshore firm based in Cyprus that also owned a share of Vorobyevs’ and Timchenko’s seafood company.

It’s also curious that the phone number indicated by Arleya Palatium in its registration document was used by Kordex, a Timchenko company which owns a 12.5 percent share in SOGAZ, the insurer of Russian state gas giant Gazprom. In 2013, the value of this share was estimated at approximately six billion rubles ($185 million). Following the introduction of sanctions against him, Timchenko transferred Kordex to his daughter.

The company has an illustrious pedigree — it was previously owned by a company that helped finance the construction of the elaborate mansion known as “Putin’s Palace” in Gelendzhik, on Russia’s Black Sea coast, which is allegedly owned by the Russian president.

Neither Timchenko nor Vorobyev explained these connections, nor did they answer questions as to whether these companies supported United Russia’s party foundation.

Enter Shoigu

Arleya Palatium also connects the foundation to the family of Russian Defense Minister Shoigu.

Though the company was a complete unknown, and had been founded just months before, it was named by the Ministry of Emergency Situations — which was then headed by Shoigu — as an investor in the construction of a rehabilitation center for firefighters and emergency workers just 300 meters from Josef Stalin’s dacha in Moscow’s Matveyevsky forest. Soon after the building was finished, Arleya Palatium moved in.

Sometime later, a diagnostic laboratory owned by the Russian firm Rekapmed appeared in the same office. This firm is majority owned by Irina Shoigu, wife of Russia’s Minister of Defense, and by Yekaterina Zhukova, wife of the first deputy chairman of Russia’s State Duma.

Contacted by reporters, Rekapmed said that the firm was founded to research eastern medicine, and that it does not collaborate with the other organizations registered at the same location. The firm also said that Irina Shoigu had only been the firm’s “temporary founder” until February 2015, and that Yekaterina Zhukova was the founder until May 2015. Nevertheless, according to state registry documents, the two women are still the company’s co-owners. Sergey Shoigu did not respond to requests for comment.

Whose money?

The case of the secretive foundations exemplifies the interrelated nature of politics and business in Russia, say observers.

A former employee of the presidential administration said that some of the people connected to the foundations — Andrey and Maxim Vorobyev, Sergey Shoigu, and Gennady Timchenko — are a fairly close-knit group who enjoy the trust of the president himself. While there are no records available to prove how much money, if any, the trio have provided to the Putin campaign, they have certainly provided it with the necessary infrastructure to collect money.

Polozov, the head of the NFPR, says that, at least since 2013, the foundation has not worked with Maxim Vorobyev and Timchenko’s businesses in any way, has never received any funds from them, and does not do so today. Polozov calls “ridiculous” the idea that the 22 foundations were made sponsors of Putin’s election campaign in order to hide the identity of the real donors.

“If somebody wanted to hide it away, they’d just hide anyway,” said Polozov.

The NFPR head said that the foundations serve the purpose of making sure donations are vetted and improper donations are quickly removed.

Polozov told reporters that many people wanted to contribute to the president’s reelection campaign, and the idea was not to single anybody out. “The foundations solved that problem,” he concluded. He assured reporters that the NFPR, at the request of regional foundations, thoroughly examines the “cleanliness” of all donations, and that the Ministry of Justice knows the donors and has thoroughly checked them.

Once again, Polozov would not disclose who exactly donates to the foundations.

It’s not even clear whether they currently receive money from state-owned companies and state institutions — but at least some of them have in the past.

In 2015, Omskenergo, a state-controlled energy company, decided to provide financial assistance to the Omsk Foundation for Regional Cooperation and Development. One year later, the Yugra Territorial Energy Company, also controlled by the state, provided charitable support to one of the local foundations (as the company’s press release says). And in 2017, the Voronezh City Council decided to grant the use of a municipal building to the Voronezh Foundation for Regional Cooperation and Development for five years, free of charge. Meanwhile, the Samara Foundation is hosted by Samara’s municipal center for communal services.

Deep pockets

The secrecy of the foundations sponsoring Vladimir Putin’s electoral campaign is not the only issue which raises questions. The financial accounting of these foundations shows that not all of them had always been wealthy enough to donate substantial sums to the presidential race. In fact, for the entirety of 2016, several earned less money than they’re currently donating to the campaign.

According to their tax filings, the Kaluga Foundation for Regional Cooperation and Development collected a little over half a million rubles ($7,600) in 2016, but donated a single sum of 15 million rubles ($227,000) to the campaign. The Volgograd Foundation, which collected five million rubles ($76,000), has mustered a one-off payment of 10 million ($152,000). The Pskov Cooperation Foundation, which scraped together 840,000 rubles ($12,700), gave three times that number to the presidential race. Meanwhile the Kemerovo Foundation, which had collected 20.9 million rubles ($315,000), poured 25 million ($380,000) into the campaign, according to the Central Electoral Commission. And all the while, all these foundations still spend money throughout the year on events and the maintenance of their organizations.

NFPR president Polozov explained that the larger sums of money being donated by the foundations can be explained because their own donors made contributions specifically for Putin’s electoral campaign. In Polozov’s words, while the foundations did not publicly announce that they are collecting funds for the presidential race, their permanent sponsors had been informed.

The Generosity of Future Generations

The list of donors to the presidential campaign includes two wealthy foundations which both gave a minimum of two million rubles ($30,300) each. These are the People’s Projects and Civic Initiatives Foundation and the Foundation for the Support of Future Generations, which are both also registered at the United Russia address in Moscow (the latter of which also uses the same telephone number). In 2016, donors gave them nearly one billion rubles.

Nobody could explain exactly which “people’s projects” or “future generations” these foundations support, nor how they came by such sums of money. But it is known that they have supported the electoral campaigns of United Russia’s parliamentarians and regional governors. Neither foundation has a website. And people listed as their directors or founders on the state registry did not want to answer questions, or assured reporters that they hadn’t had anything to do with the foundations for a long time.

The President of the People’s Projects and Civic Initiatives Foundation, Olga Tomenko, asked reporters to call back, and then stopped answering her phone altogether. Yury Puzynya, one of the co-founders of both foundations, asserted that he hadn’t had anything to do with them for over two years.

“I haven’t worked for United Russia since 2015, I passed everything onto… Let’s stop this conversation,” said another of the co-founders, Olga Shabalina.

Unusually, a representative of United Russia told reporters that the party knows nothing about its two wealthy benefactors.

Why Now?

The reason behind the change from individual support to Putin, as has been done in the past, to the new wall of opaque foundations, is unclear.

Some experts believe one possible reason could be to “not spoil the whole picture of donations to Putin’s election with companies and individuals,” since in previous years some donations to his campaign had to be returned for various reasons. The process of screening undesirable donors and casting them aside had taken a lot of time and energy.

It’s also possible that this method of financing was chosen so that sponsors would not be put off by foreign sanctions.

“Some sponsors might be disturbed by the risk of suddenly appearing in a sanctions list due to their supporting Putin. Others, it’s possible, are already under sanctions and do not want their names and the names of their companies publicly listed among the donors to the presidential electoral campaign,” suggests Golos coordinator Andreychuk.

OCCRP, 14 March 2018