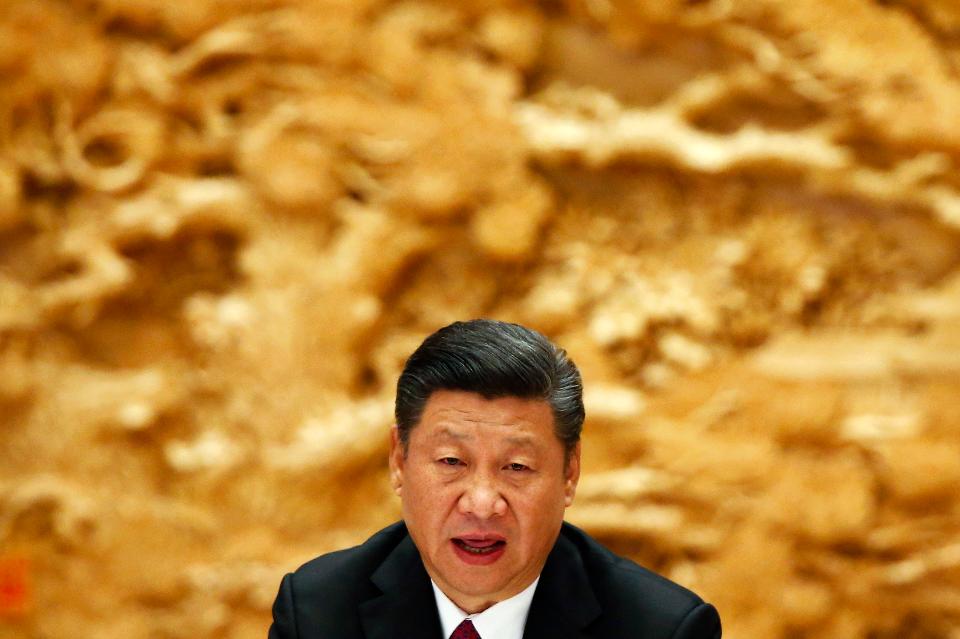

The Beijing airport is still draped with One Belt, One Road banners, a week after the close of the summit here devoted to the massive transcontinental infrastructure initiative. Launched in 2013, President Xi Jingping's ambitious project still gets little coverage in western media.

The Beijing airport is still draped with One Belt, One Road banners, a week after the close of the summit here devoted to the massive transcontinental infrastructure initiative. Launched in 2013, President Xi Jingping's ambitious project still gets little coverage in western media.

For many, the summit last week is known only as the venue where Vladimir Putin surprised everyone by spotting a piano and sitting down to play the unofficial anthem of Moscow. (The immediate appearance of his videographer undermined the impression of spontaneity.)

So, what was Putin doing in Beijing last week, apart from playing the piano? He was there to ensure Russia's stake in President Xi's bid to move China to center stage in global affairs. He was one of 29 heads of state in attendance. Putin and others looked on as Xi pledged $113 billion to the initiative. Projects to date have not been consistently documented, but the stated goal is to focus on substantial transportation and power initiatives: roads, railways, ports and power plants and the extraction and transportation of resources.

One Belt, One Road (OBOR) is meant to evoke the Silk Road trade routes dating back to the Han Dynasty: the Silk Road Economic "Belt" and the Maritime Silk "Road." Linking the project back to the ancient trade route is, one suspects, meant to make it seem a natural and benign role for China. And there's no question that infrastructure-poor regions that fall along the route will benefit from well-run, transparent projects of this kind, if indeed the projects are well-run and transparent.

While the geographic focus of the project may seem regional, the scale of its ambitions and potential impact are global. A threshold dilemma for the United States is that there are large contracting opportunities for U.S. companies working on OBOR projects, but it's China's initiative and advances China's soft power. This presumably explains why the U.S. has waffled around the edges of the project, while piano-playing Putin entertained some of the 65 OBOR nations present.

But the greater challenge for U.S. businesses is that Chinese funding means Chinese rules. This is likely to be bad news for transparency. While we have seen China crack down on corruption under Xi, efforts have been focused within China, reaching across borders only to nab Chinese citizens who have fled with their corrupt bounty. The Chinese enforcement agencies have never brought an action against a Chinese entity for bribery abroad in spite of rampant anecdotal evidence that many Chinese companies use bribery as a business strategy across Asia and Africa. That track record shows no signs of changing.

Couple this apparent indifference to bribery beyond its borders with the fact that the 65 OBOR countries include some of the most notoriously corrupt in the world. Four OBOR countries are amongst the eight riskiest in the world according to the TRACE Matrix developed by my organization: Yemen, Cambodia, Myanmar and Syria. Most others (Pakistan, Vietnam, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Iran and others), fall in the bottom half.

OBOR may well result in some new jobs for U.S. companies, but these contracts will see the United States as the junior partner to China in countries where neither the beneficiary nor the lender has shown much appetite for transparency or good governance.

Alexandra Wrage is the founder and president of TRACE, an organization committed to increasing commercial transparency and bolstering good governance.

Forbes.Com, 23.05.2017