Joanna Lillis is a freelance journalist specializing in Central Asian affairs who has been based in Kazakhstan since 2005.

Joanna Lillis is a freelance journalist specializing in Central Asian affairs who has been based in Kazakhstan since 2005.

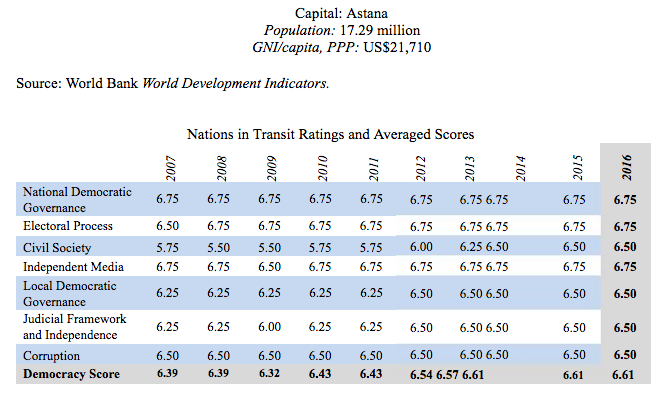

In 2015, Kazakhstan remained a consolidated authoritarian regime. The image-conscious government employs a host of western PR companies to burnish its reputation abroad, where it presents itself as a “young” and open-minded country on a gradual trajectory toward democracy. It capitalizes on its relative—if faltering—economic prosperity compared to its neighbors and promotes an image of tolerance and intercommunal harmony among its multiethnic population. Behind the spin and the veneer of wealth, however, political repression remains intense. In 2015, political freedoms continued to be heavily curtailed. No viable opposition forces were able to operate, the few remaining independent media outlets faced measures of intimidation ranging from libel trials to suspension and closure, and the country’s embattled civil society operated under intense scrutiny and pressure, with activists arrested and jailed on broad charges which are liable to subjective interpretation.

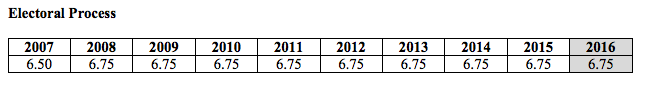

In April, Nursultan Nazarbayev, the 74-year-old president who has ruled the country for a quarter of a century, cemented his grip on power, winning reelection in a landslide with 97.75 percent of the vote. In the period since independence, elections in Kazakhstan have increasingly become stage-managed events designed to shore up the power of Nazarbayev and his ruling Nur Otan party rather than offer voters a choice about who rules them, and this election was no different.

Nazarbayev faced no genuine opposition challengers, running against two stalking horses from progovernment parties standing to lend a semblance of competition to the vote. They did not criticize Nazarbayev during the lackluster campaign, and at times appeared to voice support for the incumbent. International election observers found that voters were offered no genuine choice in the election and pointed to a lack of credible opposition in the country overall. Nazarbayev offered a half-hearted apology for the size of his election victory, but said that it would have been “undemocratic” to interfere with the results. His remarks suggested that he did not acknowledge flaws in Kazakhstan’s electoral process or the absence of opposition candidates as factors contributing to the scale of his victory.

Although Nazarbayev has previously spoken of the need to create a resilient political system that will withstand his eventual departure from office, in 2015 he made no moves to reform the highly centralized system centered on the powers of the presidency that he has shaped. In 2015, he announced a major 100-step reform program to fulfill his election manifesto pledges, which aimed to introduce greater institutional transparency and effectiveness. If the reforms are implemented in full and in good faith, this is a positive step that will improve accountability at many levels of public administration. However, the reform program contained no pledges of electoral reform to the super-presidential political system over which Nazarbayev presides without any functioning checks and balances. This system creates political risks for the post-Nazarbayev future, since it may fracture when he eventually leaves office. Meanwhile, the appointment of the president’s daughter Dariga Nazarbayeva as deputy prime minister in September further boosted the influence of the Nazarbayev family over the executive branch.

The centrality of Nazarbayev’s personality to Kazakhstan’s political system was highlighted in September and October, when the administration staged celebrations of 550 years of Kazakh statehood in a nation-building exercise. The statehood celebrations, new to Kazakhstan this year, appear to be an indirect response to Russian president Vladimir Putin’s August 2014 remarks that “the Kazakhs had never had statehood” prior to the presidency of Nazarbayev. The festivities fed the burgeoning cult of personality surrounding Nazarbayev, with the state propaganda machine depicting him as the founding father of Kazakhstan’s independence.

For the government, promoting a positive image of Nazarbayev is always a focal point of any national celebration or event. In 2015, however, it became even more crucial to shore up the president’s popularity amid an economic slowdown. A combination of low oil prices and economic downturns in neighboring Russia and China (both major trading partners) put pressure on the economy, translating into slow growth of 1.2 percent (compared to 4.3 percent in 2014) and a currency depreciation which hit living standards and public confidence. Nazarbayev enjoys genuine popularity among the public, which—under the heavy influence of state propaganda—credits him with years of rising living standards, political stability, and relative ethnic harmony. In the face of economic pressures that are likely to endure for several years, the government is determined to ensure that the public does not blame Nazarbayev personally for the downturn and to maintain his high levels of popularity.

The space for opposition politics shrank further in 2015, with the court-ordered closure of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan in August leaving no genuine opposition parties functioning. In recent years, the authorities have either closed or co-opted some parties, while others have split amid internal differences or abandoned their political activities in the face of official intimidation of leaders and activists.

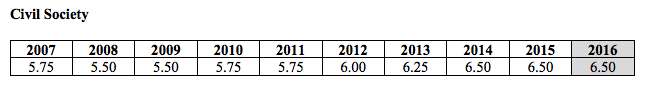

Civil society remained under intense pressure in 2015. Restrictive amendments to Kazakhstan’s Criminal Code, Criminal Procedural Code, and Code on Administrative Violations came into force in January, placing further restrictions on public assembly and criminalizing the spreading of rumors, making it punishable by up to 10 years in jail. Maina Kiai, the UN’s special rapporteur on the right to freedom of assembly and association, concluded after a visit to Kazakhstan in 2015 that the government severely restricts civil liberties guaranteed by the constitution, including the rights to freedom of assembly, conscience, and expression. Other restrictive legislation adopted in 2015 included a new Labor Code restricting labor rights (passed in November), and a law on funding for nongovernmental organizations (passed in December), which effectively granted the state a monopoly on deciding which nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) receive funding and for what types of activity. The regime continued to wield a controversial law on religion adopted in 2009, fining and jailing religious group leaders and worshippers found in breach of its stringent requirements. In a positive step, the Constitutional Court struck down a bill passed by parliament that would have criminalized “propaganda” of homosexuality to minors in May.

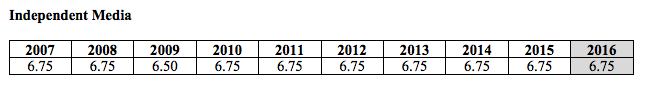

Independent media outlets faced multiple obstacles in exercising their constitutional right to freedom of expression in 2015. The Adam Bol current affairs magazine lost a protracted court battle against closure in February, and a successor outlet called Adam was suspended on a technicality in August and closed down altogether in October. The independent Nakanune.kz website—set up by former journalists from Respublika newspaper, which was closed in a crackdown on independent media in 2012—came under financial pressure after one of its journalists was fined $100,000 in a libel case in June and then jailed in December pending an investigation into charges of disseminating false information.

Websites and social media accused of hosting “extremist” content were blocked with court orders on numerous occasions in 2015, and the authorities also exercised legal powers acquired in 2014 to block websites or shut off social networks without court orders. The authorities also used the tactic of targeted blocking of reports rather than outlets, often—but not always—on grounds of allegedly extremist content.

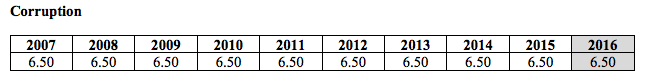

High-profile corruption cases suggested that graft remained rife in 2015. Senior officials organizing the prestigious EXPO-2017 international exhibition, which will take place in Astana in 2017, were detained on suspicion of embezzling millions of dollars of state funding for the facilities in June, and Serik Akhmetov, a former prime minister and the most senior figure to face graft charges in Kazakhstan in many years, went on trial on embezzlement charges in August and was sentenced to 10 years in jail in December. In July, Nazarbayev warned that there were “no untouchables” in Kazakhstan when it comes to corruption, but, like other high-profile corruption trials in recent years, Akhmetov’s trial took place amid suspicions that it had more to do with inter-elite factionalism than genuine will to root out corruption.

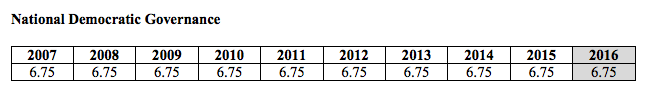

No score changes.

Outlook for 2016: Nazarbayev is likely to remain entrenched in power throughout 2016. He is unlikely to undertake reforms to put in place the resilient political system featuring checks and balances on presidential rule that he says Kazakhstan requires to withstand an eventual transition of power. In 2016, Kazakhstan will face the same economic challenges that caused a slowdown in 2014 and 2015: low oil prices and the repercussions of a recession in Russia and lower growth in China, both major trading partners. Falling living standards may gradually corrode support for Nazarbayev’s regime. Major public protests with the potential to threaten the established order, however, are highly unlikely, firstly because many citizens will blame international economic turmoil rather than domestic policies for the downturn (a message constantly reinforced by the state propaganda machine); and secondly because Astana’s repressive attitude toward public assembly has instilled a fear of protest in many people who are wary of arrest and prosecution.

MAIN REPORT

President Nursultan Nazarbayev has ruled Kazakhstan for a quarter of a century and, despite previously speaking of the need to create a resilient political system that will withstand his eventual and inevitable departure, took no steps in 2015 to reform Kazakhstan’s highly centralized political structure. In April, the 74-year-old president—who is known by the official title of Leader of the Nation and enjoys a personal exemption from constitutional presidential term limits—cemented his grip on power by winning a landslide reelection for another five-year term.

Kazakhstan’s entire system of governance rests on the executive branch. Nazarbayev and his ruling Nur Otan party control all institutions of power at the national and local levels, including the parliament, the military, and the security apparatus, and even offices that are nominally independent, such as the Central Electoral Commission and the human rights ombudsman’s office. The president appoints and may dismiss the prime minister, who is responsible for executing policies rather than formulating them. The rubber-stamp bicameral legislature, which contains only loyal presidential supporters, can be dissolved by the president at any time under the constitution. With no independent institutions to perform effective checks and balances on power, and no evidence that building such institutions is on the presidential agenda, Kazakhstan remains at risk of a major political crisis when its current president leaves office.

In May, following his reelection, Nazarbayev unveiled a major reform program called “100 Concrete Steps to Implement Five Institutional Reforms,”1 outlining measures to meet his manifesto pledges of creating a transparent, accountable government; professionalizing the civil service; ensuring the rule of law; boosting industrialization and economic growth; and promoting unity in multiethnic Kazakhstan. It contained no political reform pledges.

In September and October, Kazakhstan staged celebrations of the 550th anniversary of Kazakh statehood in a nation-building exercise designed to foster patriotism at home and make a geopolitical point abroad, after Russian President Vladimir Putin had appeared to question the country’s credentials as a sovereign state.2 The festivities fed the burgeoning cult of personality surrounding Nazarbayev, with the state propaganda machine depicting him as the founding father of Kazakhstan’s independence.

Nazarbayev remained genuinely popular in 2015 despite the economic slowdown caused by low oil prices and the repercussions of downturns in neighboring Russia and China, both major trading partners. This resulted in the slowest growth seen for six years in 2015, at 1.2 percent (compared to 4.3 percent in 2014, when the first signs of the slowdown emerged). In August, the central bank abandoned its policy of propping up the currency and moved to a free float, after which the Kazakh tenge lost some 50 percent of its value. The previous year, a currency devaluation had sparked rare (albeit small) public protests in Almaty, but there was no unrest over the currency depreciation in 2015. Public expressions of disaffection were largely limited to social media, but discussions there indicated high levels of discontent at the tenge’s fall in value, which resulted in a drop in the hard currency value of citizen’s earnings, a rise in the local currency cost of dollar-denominated debts that many people hold, and a rise in the cost of imports. In 2015, the economic downturn hit living standards and dented public confidence in a manner that was worrying for an administration used to high levels of public support.

In September, Dariga Nazarbayeva, the president’s daughter, was appointed deputy prime minister by her father in a move that increased the Nazarbayev family’s power over the executive branch.3

Nazarbayeva had held influential positions in the rubber-stamp parliament, where she was a Nur Otan member of parliament (MP) and deputy speaker of the lower house, but had no previous experience of executive administration. In December 2014, her son, Nurali Aliyev, was appointed deputy mayor of Astana without any prior experience of holding an executive government position.4

In February, Rakhat Aliyev, Nazarbayeva’s ex-husband and father of Nurali Aliyev, a once powerful official and businessman who fled Kazakhstan in 2007 during a feud with Nazarbayev, was discovered hanged in a prison cell in Austria, where he was on trial for the murder of two Kazakh bankers in 2007.5 In December, an Austrian judge rejected claims he was murdered, after an additional investigation prompted by the suspicious circumstances of his death.6 Aliyev operated with impunity for many years in Kazakhstan, but after he fell afoul of Nazarbayev in 2007, the authorities pursued him abroad with extradition requests (which were denied) and tried him twice in absentia in Kazakhstan on charges ranging from abduction to coup plotting. He was sentenced to a total of 40 years in jail in 2008.7

The authorities have relentlessly pursued former senior officials and businessmen who have fled abroad, typically only issuing arrest warrants after the targets have fallen afoul of the regime for political reasons. This sends a clear message of deterrence to other potential dissenters who may consider seeking sanctuary abroad. In 2015, Kazakhstan continued to seek the extradition from France of oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov to face fraud charges. In October, the French government signed an order to extradite Ablyazov to Russia,8 despite pleas from campaigners not to extradite him to any ally of Kazakhstan that might send him on to his home country. Campaigners say he risks ill-treatment and the denial of his right to a fair trial in Kazakhstan because of his record of political opposition to Nazarbayev.9 Ablyazov was arrested in France in 2013 and remained in detention at year’s end pending a final appeal against the extradition order.

In December, Nazarbayev removed political heavyweight and trusted ally Nurtay Abykayev as National Security Committee chairman and nominated him for a seat in the Senate in a reshuffle believed to have been sparked by Abykayev’s ill health.10 Nazarbayev promoted his nephew Samat Abish to first deputy director of the National Security Committee, continuing the trend of moving members of the president’s family into positions of power.11

Nazarbayev won reelection in a snap presidential election held in April with 97.75 percent of the vote.12 He faced no genuine opposition challengers; the two other candidates, Turgun Syzdykov of the Communist People’s Party of Kazakhstan, who won 1.6 percent of the vote and Abelgazi Kusainov of Nazarbayev’s own Nur Otan party, who won 0.6 percent), were little-known stalking horses from progovernment parties standing only to lend a semblance of competition to the election. Neither

offered any criticism of Nazarbayev or his record during a lackluster campaign, and at times they appeared to voice support for the incumbent.13

This was the second time that Kazakhstan had held a presidential election featuring no genuine opposition challengers. In 2011, the opposition boycotted the proceedings, arguing that they did not create a level playing field. In 2015, there were no remaining effectively functioning opposition movements in Kazakhstan that could field candidates to challenge the incumbent.

The snap election was held 20 months ahead of schedule, which officials explained was designed to grant Nazarbayev a fresh mandate to tackle Kazakhstan’s economic slowdown. However, it was unclear why a president elected only three years previously with 95.5 percent of the vote needed a fresh mandate. It is likely that the administration preferred to entrench Nazarbayev in power for another five years in 2015 as the country faces the prospect of protracted economic problems, before a possible rise in popular discontent. The election also offered an opportunity to reaffirm the hierarchy of the ruling party and the loyalty to the center of local authorities, who were required to demonstrate their capacity for mobilizing voters in support of Nazarbayev.

International election observers from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) found that a “lack of genuine opposition limited voter choice” in the election, which was “efficiently administered” but featured “serious procedural deficiencies and irregularities.”14 The mission’s findings pointed to substantial restrictions on freedom of expression and said that reports of pressure on voters to attend rallies and turn out to vote had raised concerns about whether they could vote freely without fear of retribution. This pressure undoubtedly contributed to the high reported turnout rate of 95.22 percent. Nazarbayev offered a half-hearted apology for the size of his election victory, remarking that “for super-democratic states such figures are unacceptable,” but said that it would have been “undemocratic” to intervene in the results.15

Rumors that parliamentary elections, which are due in January 2017, would be called early persisted throughout the year, fueled by developments on the party political scene involving small parties. In September two progovernment parties, the Party of Patriots and the Auyl party, merged to create the Auyl People’s Patriotic Party led by Ali Bektayev. 16 In July civil society activists led by Olesya Khalabuzar announced plans to set up a new opposition party named Justice, which did not have enough members to apply for registration by year’s end.17

Restrictive amendments to the Criminal Code,18 Criminal Implementation Code,19 and Code on Administrative Violations20 came into force on January 1, including sanctions for forming, financing, or participating in any unregistered association; for communicating in support of an unsanctioned gathering; and for interfering with the functions of a state agency. The new legislation also criminalized the spreading of rumors, making it punishable by up to 10 years in jail.21 Several people were fined on this charge in 2015, and in August a man was sentenced to two and a half years in jail.22

Maina Kiai, the UN’s special rapporteur on the right to freedom of assembly and association, concluded after a January visit to Kazakhstan that the government severely restricts civil liberties that

are guaranteed under Kazakhstan’s constitution, including the rights to freedom of assembly, conscience, and expression.23 Dissent is sometimes criminalized, he said, and engaging in political activities is “difficult, discouraging and sometimes dangerous.” During Kiai’s visit, the authorities preemptively detained journalist Guljan Yergaliyeva to prevent her from attending a public meeting in Almaty to publicize legal proceedings against her magazine, highlighting what Kiai described as severe restrictions on freedom of assembly.24

Protesters must apply for permission to hold protests with the local authorities, which regularly denied such permission in 2015. In September, Almaty City Hall denied activists leave to hold a protest against currency devaluation.25 Activists who stage protests without permission are generally arrested and either fined or jailed for short periods. Activist Yermek Narymbaev was twice imprisoned in 2015 on charges of holding unsanctioned protests in Almaty, for 15 days in July26 and for 20 days in August.27

In August, a court ordered the closure of the opposition Communist Party of Kazakhstan on several technicalities, including that it fell 1,400 members short of the minimum threshold of 40,000 members for a political party and that it had registered incorrect addresses.28 The closure left no genuine opposition parties actively functioning in Kazakhstan. In recent years the authorities have either closed or co-opted some parties, while others have split due to internal differences or abandoned their political activities due to intimidation. In 2012, the Alga! party was banned, and its leader Vladimir Kozlov was jailed on charges of fomenting unrest in the town of Zhanaozen.29 In 2013, Bolat Abilov, the leader of the Azat party, quit politics, leaving his party moribund.30 The National Social Democratic Party, which positions itself as an opposition movement and is led by Zharmakhan Tuyakbay, was largely inactive.

In November, Kazakhstan approved a new labor code31 despite opposition from trade unionists, who had argued that clauses granting employers greater freedom to amend contracts and dismiss staff undermined workers’ rights.32 The code also aimed to secure the right to work of people with disabilities through quotas and a state commitment to reimburse expenditures to adapt workplaces for the disabled.

In December, Nazarbayev signed off on a law on funding for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) which significantly tightened government control over the operations of civil society groups.33 It established a single state operator via which all funding for NGOs must be channeled,34 effectively granting the state a monopoly on deciding which NGOs receive funding and for what types of activity. In October, UN rapporteur Kiai had urged the authorities not to allow the bill to become law.35

In May, the Constitutional Council struck down pending legislation that would have criminalized “propaganda” of homosexuality to minors.36 Kazakhstan struck down the law following pleas from international sports stars to reject the bill in the run-up to a decision on its bid to host the 2022 Winter Olympics, which Kazakhstan subsequently lost to China.

The authorities continued to make wide use of a controversial law on religion adopted in 2009, fining and jailing religious group leaders and worshippers found in breach of its stringent requirements. In 2015, a total of 19 members of a single Islamic movement, Tablighi Jamaat, were convicted under the law on charges of belonging to a group banned in Kazakhstan. Eight of them were jailed.37 The charge of inciting religious enmity was also used against minority communities: in December, Seventh Day Adventist Yklas Kabduakasov was jailed for two years on the charge.38

In February, there was an intercommunal clash between the Kazakh and Tajik communities in southern Kazakhstan.39 Sparked by a petty dispute, it revealed under-the-surface ethnic tensions that the government refused to acknowledge. The administration promotes ethnic unity as a core value, by and large successfully, but discussion of ethnic tensions is taboo and the authorities seek to prevent open debate on the issue.

In April, prosecutors opened a criminal case against civil society activist Murat Telibekov on charges of inciting ethnic enmity, over content that appeared online which purported to be from an unpublished book that he had written some 20 years previously. In October, police arrested activists Serikzhan Mambetalin and Yermek Narymbayev on the same charge for re-posting and discussing excerpts of the book (which Telibekov said were in fact forged) on social media.40 They went on trial on 9 December41, and their trial continued at year’s end despite Narymbayev—who suffers from high blood pressure and a heart condition—complaining of ill health.

The charge of incitement to ethnic, religious, tribal, social or class enmity, which carries a prison sentence up of up to 20 years in aggravated cases, was widely used against activists and social media users in 2015, particularly in cases where they were discussing ethnic relations in Kazakhstan or relations between Kazakhstan and Russia.42 Authorities monitored such online discussions closely, and one social media administrator, Igor Sychev, was jailed for five years in November on the charge of calling for separatism, which was introduced into law in 2015.43

In February, the current affairs magazine Adam Bol was officially shuttered after losing its appeal against a closure ordered in 2014, on the grounds that it had advocated for war in its reporting on the Ukraine conflict.44 The closure—which followed a protracted court battle with Almaty city hall, which lodged the case, and a hunger strike by editor Guljan Yergaliyeva—sparked expressions of concern from press freedom campaigners.45

Journalists from Adam Bol set up a successor outlet, Adam, which operated for six months before it, too, was suspended in August. The three-month suspension came on the grounds that it had failed to publish in the Kazakh language, despite stating in its registration documents that it would publish in Kazakh and Russian. Local press freedom watchdog Adil Soz condemned the closure as anti- constitutional and said that Adam was under no legal obligation to publish in Kazakh46, and Reporters Without Borders condemned the ruling as “discriminatory and utterly disproportionate.”47 In September, Adam editor Ayan Sharipbayev was ordered to pay a $180,000 libel fine in a case brought by deputy intelligence chief Kabdulkarim Abdikazimov over a report in the magazine.48

In June, Guzyal Baydalinova of the independent Nakanune.kz website was fined $100,000 in a libel case filed by Kazkommertsbank over a report on corruption in Almaty’s construction industry.49 In December, authorities raided the newspaper’s offices and searched its journalists’ apartments during an investigation into charges of disseminating false information about Kazkommertsbank.

Baydalinova was jailed pending the outcome of the investigation and remained in prison at year’s end. Journalist Yuliya Kozlova was placed under investigation on charges of possession of narcotics that investigators said they found during the raid, which she said were planted.50 Nakanune.kz was set up by former journalists from the Respublika newspaper, which was closed—along with associated outlets—in a crackdown on independent media in 2012.

Websites and social media accused of hosting “extremist” content were blocked with court orders on numerous occasions in 2015. In September, a court ordered video hosting services Vimeo and DailyMotion and photo hosting platform Flickr blocked for hosting material deemed to promote extremism. In 2015, websites were also blocked without court orders and without official acknowledgement. The current affairs websites Ratel.kz and Zonakz.net were blocked without explanation in September, and international outlets such as the Avaaz campaigning website and LiveJournal blogging platform were also blocked during the year. The editor of Central Asia regional site Fergana.ru says his site was blocked starting in August.51 In 2014, amendments to the communications law allowed the authorities to block websites or shut off social networks without a court order on the grounds that they contain terrorist or extremist content or calls to participate in “mass unrest.”52 In December the government announced plans to compel Internet users to install a

national security certificate on their devices that would allow the state to access, monitor and edit https-encrypted traffic.53

The authorities continued to employ the relatively new tactic of targeted blocking of reports rather than outlets, often—but not always—on grounds of allegedly extremist content. In March, RFE/RL was blocked after reporting on an Islamic State recruitment video targeting Kazakh speakers. Reports about Yergaliyeva’s hunger strike were also systematically blocked, as were reports on the ethnic unrest in south Kazakhstan in February.54 In November a new law on access to information was approved, in a move welcomed by civil society campaigners.55

The authorities occasionally detained journalists attempting to exercise their lawful right to cover public protests. In July, an RFE/RL reporter was detained in Astana while attempting to report on a protest at the presidential administration.56

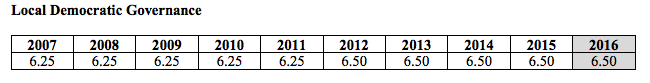

In 2015, the government embarked on the second stage of its 2013-2020 local governance strategy, during which it has promised to hand greater governing and financial powers to local government.57 In March, the government adopted new rules on local government financing58, and in November a legislative reform package59 intended to grant local authorities greater financial powers and increase the involvement of local populations in the decision-making process was approved.60 The package includes measures specifying how public local assemblies to discuss financing should be organized; measures to boost public involvement in monitoring the use of budget funds; measures to grant akims (mayors) greater decision-making and fund-raising powers; and measures placing revenues from certain taxes (including income tax on small businesses that is not deducted at source; transport taxes imposed on locally-registered companies; and taxes on local government property and street advertising) and fines into the hands of local government. Local community assemblies will have input into deciding on how budget funds should be used, and will conduct monitoring of their use every six months to boost transparency and accountability. In November, a law was approved obliging local authorities to set up public councils to allow public oversight at all levels of local government starting in 2016.61

Despite these legal changes, the system still remains highly centralized. The mayors of all major cities and governors of Kazakhstan’s 14 regions are presidential appointees, with no accountability to the communities they serve. In smaller towns and villages, mayors were elected via indirect suffrage in 2013, but—although the authorities touted these first-ever mayoral elections in Kazakhstan as a major step towards democratization—the elections have not to date demonstrably increased the independence or democratic accountability of local government. Mayoral elections took place in towns and villages inhabited by only 45 percent of Kazakhstan’s total population, and all candidates were elected by maslihats (local councils), which are overwhelmingly dominated by Nur Otan.62

The most significant local government appointment of 2015 was made in August, when Nazarbayev appointed a new mayor of Almaty. Baurzhan Baybek, formerly first deputy head of the ruling Nur Otan party, replaced Akhmetzhan Yesimov, who had been mayor of Almaty for seven years.63

Western-educated Baybek attracted praise from the Almaty public for a more open and responsive style of government, in which he used social media to deal with complaints64 and react to controversies.65 There were signs that the new mayor and his team had clashed with the old guard at city hall, where three deputy mayors resigned in a single day in October.66 In November, Baybek launched a public consultation process about urban development plans for Almaty as part of government efforts to improve public participation in local government.67 Ultimately, however, the mayor remains accountable to the president over and above the Almaty public, and under him repressive policies such as prosecutions of independent media instigated by city hall and denial of permission to hold protests continued in 2015.

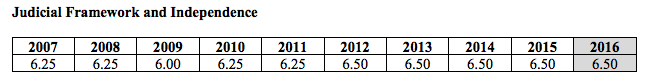

Kazakhstan’s constitution recognizes the separation of powers and safeguards the independence of the judiciary, but in practice the courts are subservient to the executive and protect the interests of the ruling elite. The president appoints judges to the Supreme Court and local courts, as well as members of the Supreme Judicial Council. The courts regularly convict public figures brought to trial on politically motivated charges, often without credible evidence or proper procedures.

In January, a new Criminal Code,68 Criminal Implementation Code,69 and Code on Administrative Violations70 came into force. The legislation reduced the number of offenses defined as serious and introduced wider use of non-custodial sentences. It also established a number of liberalizing measures in places of detention, including greater freedom of movement for prisoners, who will only be locked in their cells at night, and greater public scrutiny over places of detention, although it is not clear what form this takes and if it will be effective in practice. The codes introduced a total of 34 new crimes, with especially harsh penalties for separatism and dissemination of false information.

In July, Vladimir Kozlov, an opposition leader controversially convicted in 2012 on charges of fomenting social unrest in order to topple the government, was transferred to a stricter detention regime for alleged breaches of prison regulations, which he denied.71 Kozlov held a brief hungerstrike in July in protest at his treatment in jail, where relatives say he was suffering from ill health and not receiving appropriate medical attention.72

In 2015, pressure was sometimes applied on lawyers attempting to carry out their professional duties.

In June, a lawyer in Kostanay Region was convicted of defaming a judge during legal proceedings and sentenced to one year of mandatory supervision.73 In January, Vadim Kuramshin, a corruption-investigating lawyer who was facing a 14-year jail sentence on extortion charges, was unexpectedly released after a jury dismissed the case against him.74

Periodic reports of abuse in places of detention surfaced in 2015. In February, a video was published online that appeared to show prison guards physically abusing detainees. The authorities investigated and said that the treatment was legal, and the video had been taken out of context.75 The authorities do occasionally act on reports of abuse in places of detention, usually by prosecuting a few junior officers. In July, three police officers received three-year prison sentences on torture charges after a man in their custody was beaten so badly he was left disabled.76

Systemic corruption thrives in Kazakhstan on the country’s oil and mineral wealth. Elites, who often enjoy immunity from prosecution or investigation, use their positions to appropriate, control, and distribute key resources for personal gain. Along with law-enforcement bodies, the Agency for Civil Service Affairs and Counteracting Corruption is the main body tasked with dealing with corruption, but it is part of a civil service in which graft is entrenched and vested interests thwart efforts to eradicate it.

In 2015, Nazarbayev made combating corruption one of his election manifesto pledges. In May, he outlined steps to root out graft and nepotism from the civil service and the judiciary in his 100-step reform program77, including plans to stage public meetings to hold officials to account, improving online reporting on the use of public funds, and creating a state body called Government for Citizens to integrate public services. In July, he warned that there were “no untouchables” in Kazakhstan when it comes to corruption.78

Nevertheless, perceptions persisted that anticorruption efforts are typically political and economic tools that allow some officials to accrue power while intimidating or constraining their rivals. There are frequent prosecutions on bribery and corruption charges, but high-level officials are rarely targets; when they are, their trials often take place amid suspicions of political motivations. In July, Serik Akhmetov—a former prime minister and the most senior figure to face graft charges in Kazakhstan in many years—went on trial on embezzlement charges79 and was sentenced to 10 years in jail in December.80 Akhmetov’s trial was widely interpreted as a symptom of inter-elite factionalism, rather than genuine will to root out corruption. One theory advanced about his arrest was that Akhmetov had come off worse in a battle for influence over the president with Karim Masimov, both his predecessor and successor as prime minister. 81

High-profile corruption cases in 2015 suggested that graft remained rife at a high level. In June, senior officials organizing the prestigious EXPO-17 exhibition, which will take place in Astana in 2017, were detained on suspicion of embezzling millions of dollars in state funding for the event.82 Reports of local government corruption rings continued to surface in 2015. In September, the mayor of Kostanay and two deputies were arrested on suspicion of taking bribes in exchange for awarding construction contracts83; they remained under investigation at year’s end.

Two European corruption investigations involving Kazakhstan were ongoing at year’s end: a French probe into suspected kickbacks paid over a lucrative helicopter deal,84 and an inquiry by the United Kingdom’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) into the affairs of Kazakhstan’s ERG (formerly ENRC) natural resources company.85 In November, the SFO said the probe no longer targeted ERG’s operations in Kazakhstan but only those in Africa.

Read more: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/NiT2016_Kazakhstan.pdf