In the three years since the death of President Nazarbayev’s former son-in-law Rakhat Aliyev, investigators and researchers have tried to piece together the schemes that allowed him to launder his significant wealth.

In the three years since the death of President Nazarbayev’s former son-in-law Rakhat Aliyev, investigators and researchers have tried to piece together the schemes that allowed him to launder his significant wealth.

The report released by the Eurasia Democracy Initiative (www.eurasiademocracy.org) follows months of painstaking research, revealing how Rakhat’s first wife, Dariga Nazarbayeva, held bank accounts in Austria containing millions of dollars with links to Rakhat Aliyev’s alleged money-laundering schemes.

The research suggests that Dariga Nazarbayeva used a passport in the name of ‘Dariga Aliyeva’ to open these accounts, which would have allowed her to potentially circumvent due diligence procedures associated with being a ‘politically-exposed person’. However, the report argues that the mere possession of such a passport is in violation of the Kazakh Criminal code, as Aliyeva was not her legal name at the time.

The article also details what is known about Dariga’s fortune, estimated at nearly $600 million, and how much of it emanates from her husband’s notorious reign at the helm of Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee, the KNB.

Dariga’s million-dollar Austrian accounts

Report by the Eurasia Democracy Initiative, in cooperation with Kazakhstani Initiative on Asset Recovery, Tom Mayne and Natala Sadykova

Evidence suggests that in 2003 Dariga Nazarbayeva used an illegal passport in the name of ‘Dariga Aliyeva’ to open bank accounts containing millions of dollars with links to Rakhat Aliyev’s laundering schemes

“$200 billion” of Kazakh money lost offshore

According to the World Bank, Kazakhstan has manged to record positive GDP growth every year since 1999. Yet it is interesting to speculate how much more this growth could have been, had billions of dollars not been lost in Kazakhstan due to corruption: one estimate suggests that 25 percent of Kazakhstan’s GDP was transferred out of the country during the first decade of independence, with $500 million lost in just one year alone. The country hardly improved its record over the next two decades: Kazakhstan languished in 122nd place (out of 180 countries) in Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index, behind corruption hotspots like Egypt, Pakistan and Colombia. Former Kazakh Prime Minister Akezhan Kazhegeldin estimates that as much as $200 billion could be held by the country’s ruling elite in overseas funds and property. It is no coincidence that the list of the richest people in Kazakhstan are a Who’s Who of those closest to President Nazarbayev: his former advisor Bolat Utemuratov, his son-in-law Timur Kulibayev, and oligarchs Vladimir Kim and Alijan Ibragimov. Indeed, the country has all the hallmarks of a kleptocracy – where a government’s leaders use their power to exploit the country’s people and natural resources in order to extend their own personal wealth.

In recent years the appearance of Kazakh officials in leaked documents – the Panama and Paradise Papers, and Offshore Leaks – have confirmed the exploitation of Kazakhstan’s natural resource wealth for the benefit of the few at the expense of the many. Former Minister of Energy and Oil, Sauat Mynbayev, was shown by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project to hold a stake worth hundreds of millions of dollars in Meridian Capital, a company with many contracts related to Kazakh oil and gas – the very sector that Mynbayev was working in, supposedly on behalf of the Kazakh people. In another example, President Nazarbayev’s grandson, Nurali Aliyev – who from 2014-2016 was the Deputy Mayor of Astana – was revealed to hold much of his $200 million fortune offshore. This should come as no surprise – Mynbayev and Aliyev were doing no different from what Nazarbayev himself has done: U.S. trial proceedings related to the infamous ‘Kazakhgate’ case in the late 1990s established that President Nazarbayev was the beneficiary of several accounts in Switzerland into which money related to Kazakh oil deals flowed. Nazarbayev used some of the money to put his youngest daughter through an exclusive Swiss school. Other money related to the scandal was used to purchase “his and hers” snow mobiles for Nazarbayev and his wife, Sara.

Rakhat & Dariga – a family business

No list of the richest, most powerful people in Kazakhstan would be complete without the president’s first daughter, Dariga, who in 2013 was ranked by Forbes as the 13th richest person in Kazakhstan with an estimated wealth of $595 million,18 much of it held offshore. How did she attain such a fortune?

The first tranche of Dariga’s wealth was earned in partnership with her notorious former husband, Rakhat Aliyev, who was renowned for his brutal tactics in misappropriating businesses in Kazakhstan when at senior roles in the Kazakh tax police and the KNB, the state’s intelligence agency. Dariga clearly benefitted from her husband’s tactics, as can be demonstrated by their joint ownership of assets in three main areas – media, sugar and banking.

Dariga and Rakhat were reported to have bought media company Karavan in 1998, and were co-owners, along with the Kazakh state, of another media company, JSC Khabar, which ran the country’s main television channel. According to opposition figure Serik Medetbekov, much of Aliyev’s business empire was misappropriated from others, including Medetbekov’s own media company, using a variety of threats and intimidation tactics.

Aliyev himself, speaking under oath in 2012, claimed a business portfolio of over 40 entities – impressive work for someone who by law was required to put all business entities in trust in 1996 when he joined public service.

Rakhat also owned more than half the voting shares of Nurbank, a mid-sized Kazakh bank which featured his son Nurali – who was just 22 at the time – as a board member. Dariga and Nurali acquired the shares after Rakhat fell out with his father-in-law in 2007, and sold them in the years that followed. Dariga also acquired and subsequently sold Rakhat’s shares in JSC Sugar Centre,[18] a company that Nurali had become president of in 2004. In addition to this, Nurali also held a position at a major French sugar company, Sucres et Denrées, where Rakhat held a 10 percent stake. Dariga and Nurali also owned all of Alma TV, a telecommunications company that provides cable television and internet services in Kazakhstan. In 2018, it was reported that Dariga and Nurali may own a building of luxury apartments and offices worth over £130 million ($181 million) in London’s famous Baker Street, home to the fictional Victorian detective Sherlock Holmes.

The money that Rakhat accrued through these companies was used to acquire assets for the benefit of his family. Testimony from one of Rakhat’s lawyers, Christian Leskoschek, indicates that when Rakhat Aliyev became Ambassador of Kazakhstan to Austria in 2002, he and Dariga purchased a house located at Veitlissengasse 9 in Vienna. Leskoschek commented, “Patience was not Ms Dariga Nazarbayeva’s strong suit and she said that I must on all accounts buy the property.” The lawyer also testified that Nurali Aliyev bought an apartment in Vienna on Rohrbacherstrasse in 2003, and that the villa next door to the Veitlissengasse property was purchased in the name of Aliyev in 2005.

As is well-known, Rakhat Aliyev was exiled to Austria in 2007, accused of attempting to overthrow the government, after he challenged President Nazarbayev’s supremacy. Rakhat was then divorced from Dariga, who subsequently attempted to reassign some of the assets that had been under the control of her husband and his associates to her. These included assets owned by Rakhat’s brother-in-law Issam Hourani, a Lebanese-born Palestinian businessman, and Issam’s brothers Devincci and Hussam. Dariga acquired a company called Universal Oilfield Supply Holdings LLP from Devincci’s brother-in-law Kassem Omar in June 2007.

Dariga also took possession of the Ruby Roz agricultural plant in the same year, and a third company owned by Devincci – the Caratube International Oil Company LLP – lost its licence in Kazakhstan in early 2008. Both Caratube and Ruby Roz were then the subject of litigation, with Issam and Devincci Hourani claiming that that they had suffered harassment due to the fallout between President Nazarbayev and Rakhat Aliyev and that they had been “deceived or coerced to assign shares in their various companies to Dariga Nazarbayeva”. The Caratube case was originally dismissed in 2012 with a tribunal finding that the claimants, the Houranis, had failed to establish the tribunal’s jurisdiction over the company, though subsequent litigation that concluded in 2017 found the Kazakh state in breach of contract, with the tribunal awarding $39.2 million to Caratube

The Austrian bank accounts

Dariga’s fortune is thus intimately tied up with Rakhat’s – any question of impropriety on how Rakhat acquired this wealth must therefore be extended to Dariga, who was clearly not only a beneficiary, but in many cases, co-owner of Rakhat’s assets, and took control of many of them after their divorce. After his banishment from Kazakhstan, Aliyev became of interest to European law-enforcement agencies: authorities of at least three countries – Austria, Germany, Malta – have investigated him for money laundering, although the Austrian money-laundering investigation regarding Aliyev dates back to at least 2005 – when Rakhat was still married to Dariga.

The investigation continued for several years. A letter from the Austrian criminal investigation authorities dated June 2007 requested information on bank accounts in Austria controlled by Rakhat Aliyev. This led to a response, dated 23 August 2007, from a Ministerial Advisor which was sent to a regional criminal court in Vienna. The letter documents all accounts controlled by Rakhat Aliyev – either directly or through associates – at Privatinvestbank in Vienna. 28 accounts are given in total, three of which are joint accounts with Dariga (all opened on 25 June 2003), and a further three where the sole signatory is given as Dariga (opened two days later on 27 June 2003). Three more Rakhat/Dariga joint accounts had been opened on 16 June 2003 at Kathrein & Co, a private bank in Vienna. Information passed to Austrian law enforcement by Kathrein & Co suggests that Rakhat and Dariga used a nummernkonto to hold both a current account and securities. A nummernkonto is a numbered bank account which provides for greater secrecy, as it means that the account holder’s name will not be included on bank statements or bank receipts. This type of account is forbidden in Germany and other jurisdictions. Information from Kathrein & Co suggests that Dariga held individual signatory powers over a nummernkonto, which at the time (on 13 June 2007) held $7 million in the current account, and a further €946,000 in securities.

The August 2007 letter then analyses transfers out of these accounts, including transfers to and from companies controlled by Rakhat Aliyev. The transfers bear all the hallmarks of money laundering, as defined in a 2013 report by the Financial Action Task Force – an inter-governmental body which sets the global standards in combating money laundering and other financial crime – which lists a number of ‘red flags’ that those working in the financial services industry should watch out for. One such red flag is: “The client is using multiple bank accounts or foreign accounts without good reason.” This could be applied to the accounts outlined by the Austrian authorities: on just two dates – June 25 and June 27, 2003 – investigators say the Aliyevs opened 13 accounts at the same bank: four in Rakhat’s name, four in his name of his father (Mukhtar Aliyev), three in Dariga’s name, and a further three joint accounts (Dariga/Rakhat). One of Rakhat’s companies, AV Maximus SA, had a total of five accounts opened on two separate days, one in 2005 and the other in 2006, and a further two accounts opened in 2004 in Kathrein Bank.

The transfers documented in the August 2007 letter also appear to raise other red flags that are included in the FATF report: “There is a lack of sensible commercial/financial/tax or legal reason for the transaction” and “Involvement of structures with multiple countries where there is no apparent link to the client or transaction, or no other legitimate or economic reason.”

Despite this, the Ministerial Advisor concludes the August 2007 letter by saying: “Investigations carried out so far have not been able to provide any evidence that the money assigned to Rakhat Aliyev and others may have originated from criminal activity.” Yet many of the companies mentioned in this document would form the part of future money-laundering investigations against Aliyev: investigators in Malta looked at transfers related to, amongst other companies, AV Maximus Trading. Aliyev’s assets were frozen by Maltese courts as part of a money laundering inquiry that reportedly was being conducted in parallel with a similar inquiry underway in Krefeld, Germany. No financial crime charges were filed against Aliyev at the time of his death in February 2015, but comments made by then European Commissioner for Justice Cecilia Malmström in response to a question submitted by a member of the European Parliament about Aliyev suggest that the cross-border nature of his financial transactions made pursuing a case more difficult, due to differences in each country’s laws.

What of Dariga’s involvement? Although there is no evidence to suggest that Dariga was involved with companies such as AV Maximus Trading, documents indicate that two of the Rakhat/Dariga joint accounts held at Privatinvest Bank AG received €13,686,230 and $4,961,796 in transfers both made on 8 August 2005. It is possible that because Rakhat had signatory control over the joint accounts, Dariga may not have known or benefitted from the transfers. However, as it was a joint account, she would be legally responsible for the funds contained in these accounts and would have been able to access them.

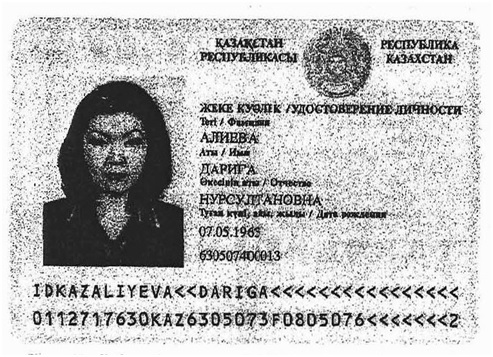

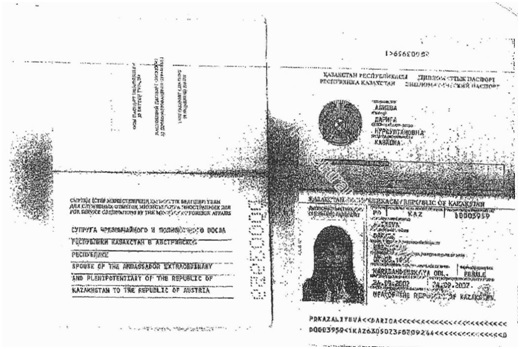

Regardless of the origin of the funds in these accounts, and her knowledge of these transfers, a further issue is raised by the name Dariga uses to open the above accounts: Dariga Aliyeva. It appears that Dariga had two passports issued in this name: one, a diplomatic passport issued in September 2002– the one used to open the above accounts – and a second, a non-diplomatic passport, number 011271763, issued in June 2000 (see above and below).

In her public life, Dariga has always been known as Nazarbayeva – there is no evidence to suggest she ever legally changed her surname to that of her then husband. The registration of Dariga’s Asar political party came in October 2003, soon after she had opened the accounts in the name of Aliyeva in June 2003. The registration of a political party would require official documentation: the fact that Dariga registered the party under the name of “Nazarbayeva” indicates that this was her legal name at the time.

It is likely that Dariga used this name to avoid enhanced due diligence procedures associated with being a ‘politically-exposed person’ – “Dariga Aliyeva” (the surname being one of the most common throughout Central Asia and the Caucasus) would not have been on PEP databases, unlike “Dariga Nazarbayeva,” which would have clearly marked her as the daughter of the president of Kazakhstan.

Dariga’s possession of multiple passports using a surname that was not her legal name could mean she is in breach of Article 325 part 3 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan – “Use of a forged document” – punishable by a fine, a 30-day period of community service, or even a probation period of up to six months. Mukhtar Ablyazov’s wife, Anna Shalabayeva, was convicted in absentia after allegedly getting a second passport from the staff of the Registration Service Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and employees of the Justice Department of the Atyrau region. Although Shalabayeva’s supporters contend that the criminal case is politically motivated, it is striking how similar the issue is to the above example of Dariga Nazarbayeva. If anything, the situation with Dariga is even more clear cut, as, while Shalabayeva allegedly obtained a second passport in her own name, Dariga’s second passport was in a name that was likely not legally hers.

It is unclear whether the Austrian law enforcement authorities ever considered the aspect of fraudulent documents and false names when investigating potential money-laundering by Rakhat Aliyev and his family.

Other law enforcement agencies – including the Prosecutor General’s Office of Kazakhstan – should bear this in mind when analyzing money flows and assets held by Dariga.

PUBLISHED BY:

Eurasia Democracy Initiative (www.eurasiademocracy.org), in cooperation with

Kazakhstani Initiative on Asset Recovery (https://kiar.center)

WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF:

Tom Mayne, independent researcher

Natala Sadykova, independent researcher

Eurasia Democracy.Org, FEBRUARY 24TH, 2019