A DECADE ago, James H. Giffen was just another of the scores of American businessmen who trudged the dreary corridors of Soviet economic ministries, shopping press releases through dark Moscow winters to promote business deals for United States companies.

Today, as Russia's post-Communist economy has slumped into dysfunction, the fortunes of Mr. Giffen, a California-born lawyer, have soared. He has retooled and branched out, forging what has proved to be a highly profitable role as deal maker and all-purpose adviser for the oil-rich former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan.

But a shadow has fallen over Mr. Giffen's relationship with the leaders of this decade-old independent state. The Justice Department has opened a criminal investigation, based on information turned up in a Swiss inquiry, into whether Mr. Giffen violated federal law in his efforts on behalf of Kazakhstan.

The investigation centers on whether he helped funnel tens of millions of dollars from American oil companies through Swiss banks, Caribbean shell companies and Liechtenstein foundations to private accounts benefiting top Kazakh political figures, including President Nursultan A. Nazarbayev.

Mr. Giffen, 59, and his lawyers denied that he violated any American laws, saying he has acted only at the direction of senior Kazakh officials. They said Mr. Giffen, who has deep, longstanding ties in Washington trade and diplomatic circles, has worked hard to bring American-style business practices to a country that many Western observers regard as insular and authoritarian.

Kazakh opposition leaders say Mr. Giffen has redefined the image of the ugly American in the post-Communist era. They accuse him of using his business acumen to help a repressive government gain credibility in the West -- which values Kazakhstan's vast oil reserves and politically strategic location -- at the same time he was profiting personally from his connections.

Experts on Kazakhstan said Mr. Giffen filled a vacuum as Kazakhstan's inexperienced leaders scrambled to reinvent a government nearly overnight. ''Giffen showed Nazarbayev and the Kazakh elite what kind of possibilities were available to leaders of oil-rich countries,'' said Martha Brill Olcott, a Kazakhstan expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, ''and in return was able to develop a position of trust that was unprecedented for a foreigner.''

In a country where horse-meat sausage and camel milk are traditional delicacies, along with cheap Caspian caviar, Mr. Giffen operates in a bubble of privilege -- with a Kazakh diplomatic passport, an armed bodyguard, a chauffeured Mercedes, a translator at his elbow and cell phones chirping as he shuttles between his offices here and the Manhattan headquarters of his company, the Mercator Corporation.

His official Kazakh title is counselor to the president, whom Mr. Giffen refers to as ''the boss.'' Mr. Giffen is also a consultant to Kazakhoil, the state-owned energy company headed by his friend Nurlan Balgimbayev, whose white-stucco bungalow is next door to Mr. Giffen's nearly identical house in an American-style subdivision beneath the snow-capped Altai Mountains that dominate this city, the country's business capital.

With consultants he hires for geological, commercial and legal work, Mr. Giffen negotiates on Kazakhstan's behalf and provides strategic advice on major oil deals between Kazakhstan and American companies. After one long day of meetings last summer in Astana, the capital, Mr. Giffen boarded a creaky Russian airliner, settled into his seat and said with a smile, ''I never cared about making money; I just love this stuff.''

Yet he has become a controversial figure in the oil business, and in Kazakhstan's political life.

Akezhan Kazhegeldin, a former prime minister who is now a principal opposition leader, said in an interview that Mr. Giffen had gained a troubling hold over Mr. Nazarbayev's thinking.

''Giffen became less objective and began advising Nazarbayev on political matters, including appointments of government officials,'' said Mr. Kazhegeldin, who lives at an undisclosed location in Europe out of fear, he says, for his personal safety. ''He then attempted to interfere with economic policies of the country.''

Mr. Kazhegeldin says Mr. Giffen should get out of Kazakhstan. Mr. Giffen replies that he is answerable only to one person: Mr. Nazarbayev.

So far, the investigation has remained at low idle. American prosecutors have subpoenaed records from several oil companies that operate in Kazakhstan, including BP Amoco, Phillips Petroleum and ExxonMobil. None of the companies appear to be a focus of the inquiry and all have denied wrongdoing. Government documents in the case indicate that prosecutors are concentrating on Mr. Giffen and whether he violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which bars Americans from paying bribes overseas, and racketeering, conspiracy and money laundering statutes.

Law enforcement officials said federal authorities were also examining whether Mr. Giffen violated the United States trade embargo against Iran, through his role as an adviser to the Kazakhstan government over an oil swap between the two countries. Neither Mr. Giffen nor his lawyers would discuss the case.

But the principal question about Mr. Giffen is whether he has played what opposition leaders consider a fixer's role in the siphoning off of Kazakhstan's oil wealth by its autocratic rulers.

In legal documents asking Swiss authorities to freeze millions of dollars, some of it in numbered bank accounts, federal prosecutors have said they suspect that more than $60 million -- paid as ''signature bonuses'' for drilling, exploration and production-sharing agreements in Kazakhstan -- was transferred through a series of Kazakh government accounts into accounts controlled by individuals including Mr. Nazarbayev, Mr. Balgimbayev and Mr. Giffen himself.

The country's leaders have accused Western governments of meddling in Kazakhstan's internal affairs. The prosecutor general, Yuri Khitrin, said the accusations of wrongdoing were ''unsubstantiated nonsense.'' Mr. Balgimbayev, too, denied that there had been any improper payments.

Mr. Nazarbayev, in the United States in September, appealed directly to Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright to unfreeze the funds. According to people familiar with that conversation, Mr. Nazarbayev said that Mr. Giffen had done nothing wrong, that the money in the frozen accounts belonged to Kazakhstan and that the United States lacked a basis for its investigation.

Dr. Albright, who met with Mr. Nazarbayev in New York as part of a series of brief sessions with foreign leaders during a United Nations conference, listened but made no offer to intercede, American officials said.

Mark J. MacDougall, a defense lawyer for Mr. Giffen, said the oil company payments were not under-the-table bribes but payments openly negotiated in contracts related to concessions in the rich offshore Caspian region.

''The Caspian transactions were documented in broad daylight by some of the most prominent law and accounting firms in America,'' said Mr. MacDougall, a partner at Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld, a Washington law firm.

Those transactions are at the core of oil development here, as Kazakhstan takes its place as a major oil-producing nation. In July, a group of oil companies announced that exploratory wells driven into the Caspian Sea bed had found heavy flows of oil and natural gas from Kashagan, 50 miles off the west coast of Kazakhstan.

Some estimates suggest that Kashagan could hold twice the reserves of Tengiz, the Kazakh onshore field that is one of the world's 10 largest oil deposits. Mr. Giffen said Kazakhstan, within 15 years, could be producing as much oil as Kuwait -- what he called a ''staggering'' production figure, 655 million barrels a year according to Oil and Gas Journal.

A Cram Course in Civics

''Over the years the president has told me, 'Look, you are my counselor,' '' Mr. Giffen said. '' 'You are supposed to tell me the truth, even if the news is unpleasant.' I have tried to do exactly that over the years, but I must tell you that delivering unpleasant information to a strong president who is impatient to build a nation is not for the faint of heart.''

The two men met in the late 1980's, when Mr. Nazarbayev was in Moscow as a provincial Communist leader and Mr. Giffen was chasing deals throughout the Soviet Union. But they did not forge a close partnership until soon after Kazakhstan declared its independence with the demise of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

Mr. Nazarbayev, presiding over a new nation with vast natural wealth, initially relied on Mr. Giffen to negotiate favorable terms as Kazakhstan began forging deals with Western oil companies.

Mr. Giffen recounted the hours they spent discussing ''basic civics'' when Mr. Nazarbayev visited the United States in 1992 to get acquainted with American officials. ''He had an insatiable appetite for information and a photographic memory,'' Mr. Giffen said. ''We both smoked at the time, and all you could see was a gray cloud.''

These days, Mr. Giffen has broadened his portfolio, advising the Kazakhs not only on oil matters, but also on economic planning, education, investments, health care, pensions and communications, often hiring consultants in areas in which he lacks expertise.

How well his lessons in Western ways are sticking is hard to say. Last year, human-rights monitors criticized a presidential election in Kazakhstan because the only credible opposition candidate was barred from running. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe concluded that Mr. Nazarbayev, who won with a Soviet-style 80 percent of the vote, ''staged a flagrantly flawed election which sullied his own reputation and set back the country's flagging democratization.''

The transactions unearthed by Justice Department and Swiss investigators also raise questions about how the business of state is conducted in Kazakhstan. According to a formal request for assistance filed under a treaty between the United States and Switzerland, the Justice Department says that on March 19, 1997, Amoco Kazakhstan Petroleum, one of the companies involved in the big offshore project in the Caspian Sea, transferred $61 million from Bankers Trust in New York in two payments to account 1215320 at Credit Agricole Indosuez, a bank in Geneva. (The Amoco unit is now part of BP.)

Three days later, the document says, Mr. Giffen and Kazakh officials began a series of what the United States government says were illegal transfers from Kazakh treasury accounts into private accounts benefiting several Kazakh leaders.

On May 21 of that year, the document says that Mr. Giffen transferred about $34.5 million to a Swiss account of a company called Tulerfield Investment Inc. According to the filing with the Swiss, Tulerfield, a shell corporation registered in the British Virgin Islands, was established for the benefit of Mr. Balgimbayev, the head of the Kazakh state oil company.

About the same time, the document says, Mr. Giffen was the intermediary in the transfer of $29 million from a numbered account at Credit Agricole to another account at the bank set up for Hovelon Trading S.A., a company registered in the British Virgin Islands that the Justice Department said ''appears'' to have been established for the benefit of Mr. Giffen.

From that $29 million, the document says, Mr. Giffen authorized several other fund transfers:

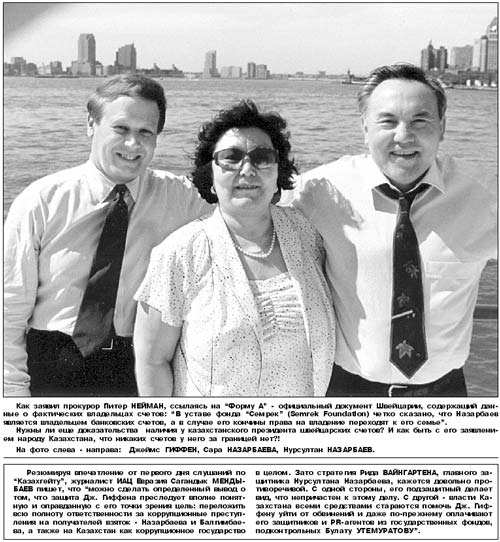

* The account of a British Virgin Islands company called Orel Capital Ltd. received $12 million. The company, the document said, appears to have been set up for the benefit of Semrek, a Liechtenstein foundation whose ''principal economic beneficiary'' appears to be Mr. Nazarbayev.

* Orchard Holding Ltd., an account created for the benefit of Brisa Inc., a company it says benefited Mr. Balgimbayev's daughter, Samal, received $8 million.

* The account of Pio Ltd., a British Virgin Islands company established for the benefit of another Liechtenstein foundation, received $6 million. The document says the foundation appeared to benefit Mr. Kazhegeldin, the current opposition leader, who said he was forced from office as prime minister by Mr. Nazarbayev's allies in 1997.

Mr. Kazhegeldin said that neither he nor any member of his family had access to these funds. The money, he added, was placed in a standing account under his control only because he held the prime minister's title, and he tried to return it. Mr. Kazhegeldin said the transaction was an attempt by Mr. Nazarbayev's allies to entrap him in a corrupt scheme -- an accusation that Mr. Nazarbayev's followers dispute.

Mr. MacDougall did not deny that the transfers occurred, but said the government had misinterpreted them.

''The payments by U.S. oil companies were deposited into escrow accounts and disbursed solely at the direction of senior officials of the Republic of Kazakhstan,'' he said. ''That money has not disappeared and was used to fund proper Kazakh government activities or is still on deposit in the banks in Switzerland.''

Spokesmen for the oil companies would not discuss the transfers in detail. Some said the companies understood that their payments were made to Kazakh treasury accounts and were unaware of any subsequent transfers to private accounts.

According to bank records obtained by The New York Times, money from some of the accounts was used for what appear to be legitimate purposes, paying geologists, lawyers, public relations consultants and other American advisers to the Kazakh government.

Other financial records suggest that nearly $1 million was spent on personal items, although the records do not show who gave or received these items. Kazakh officials said many of the purchases were made by the government as official gifts for overseas dignitaries.

Mr. MacDougall said that neither he nor Mr. Giffen would discuss the details of these transfers.

The Growth of an Inquiry

The events that spawned the Justice Department investigation appear to have begun in 1999, when the Kazakh government itself began investigating Mr. Kazhegeldin, the former prime minister. Kazakh officials contacted the authorities in Belgium, where they apparently believed that Mr. Kazhegeldin had financial holdings, and Belgian investigators later sought the assistance of the Swiss, who froze more than $100 million in Kazakhstan-related accounts.

Swiss officials began their own inquiry. In January, they notified American prosecutors about what they regarded as a pattern of suspicious transactions involving American and European oil companies' dealings with Kazakhstan.

That prompted the Justice Department to start yet another investigation, which came to light in June, when federal prosecutors filed a formal request with the Swiss magistrate investigating the matter, Daniel Devaud. The United States request asked the Swiss to freeze certain bank accounts and turn over records about them.

To American law enforcement officials, the existence of off-the-books accounts and payments to offshore corporations and Liechtenstein foundations are glaring signs of possible corruption. Nonetheless, American officials and defense lawyers alike said that prosecutors might have problems ever bringing a case under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act or other statutes.

To do so, they said, would require proving that the oil companies, the Kazakh officials and Mr. Giffen all knew and had agreed that the payments were bribes tied to winning oil concessions -- a difficult evidentiary hurdle. Moreover, each of the oil deals at issue was monitored by lawyers at every stage, and the payment of signature bonuses -- as the transactions are described by all the parties -- is, indeed, customary practice in the oil business.

''If in fact Mr. Giffen is transferring funds at the request of a foreign government, it is hard to see how that kind of authorized conduct could violate the act, no matter who ends up receiving the funds,'' said Gregory Husisian, a Washington lawyer who has written extensively on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

So far, the American investigation does not appear to have moved beyond an effort to analyze financial information about the transactions with Kazakhstan. Federal law enforcement officials said they were hunting for a breakthrough document or a witness willing to provide evidence of a violation -- without which there is unlikely to be a case.

Adapting to a New Era

Mr. Giffen's emergence as a powerful figure in Kazakhstan came after more than three decades of trying to promote American trade in the Soviet Union. He turned his thesis from the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law into a book, ''The Legal and Practical Aspects of Trade with the Soviet Union,'' and began his international business career working for a minerals trading firm. By the early 1970's, he was a vice president of a subsidiary of Armco Steel, later bought by AK Steel, that sold oil-field equipment in Russia and other countries.

He soon emerged as a close associate of Armco's president, C. William Verity Jr., a longtime advocate of increased trade with the Soviet Union. In the late 1970's, Mr. Verity became chairman of the United States-Soviet Trade and Economic Council, a group that sought to persuade the governments of both countries to relax trade restrictions; a decade later, he served as commerce secretary in the Reagan administration.

The president of the trade council from 1978 to 1980, Michael V. Forrestal, also became Mr. Giffen's friend. (Mr. Forrestal, a senior partner at the Shearman & Sterling law firm in New York and a former member of the senior staff of the National Security Council, died in 1989.) Even today, the firm continues to benefit from the relationship, as one of Kazakhstan's principal legal advisers on oil and gas development deals.

Mr. Giffen's projects were buffeted by the ebb and flow of American-Soviet relations. In 1979, he was in Paris celebrating his biggest triumph, a contract for a $350 million steel plant in Russia, when President Jimmy Carter canceled the deal in reaction to the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

But Mr. Giffen said he never abandoned his enthusiasm for global trade. ''I was trying to change the world,'' he said.

His efforts brought him into frequent contact with Washington policy and intelligence circles. He helped the Carter administration enlist American companies to support Senate ratification of SALT I, the strategic nuclear arms reduction treaty. He got to know Robert S. Strauss, who later became the American ambassador to Moscow. After his tenure there in 1991 and 1992, Mr. Strauss returned to his position as a senior partner at Akin, Gump, the law firm that represents Mr. Giffen in Washington.

Like many other American executives overseas, he long maintained an informal relationship with the Central Intelligence Agency, mainly responding to inquiries about oil and gas matters, he said.

''Since I have become counselor to President Nazarbayev, I do not meet with U.S. government officials unless requested by the government of Kazakhstan,'' Mr. Giffen said. ''Of course, I have met U.S. officials for years at functions where both government and private-sector representatives participate.''

In May 1984, Mr. Giffen left Armco to open the Mercator Corporation; it started operations with a five-year contract with Armco. The board included Mr. Verity, the former Commerce Secretary Juanita M. Kreps and the former Treasury Under Secretary Robert V. Roosa.

Still trying to promote business activity, Mr. Giffen helped devise the American Trade Consortium and sought out Chevron and other companies, like Ford Motor, Johnson & Johnson and Kodak, to open new markets for United States companies in the Soviet Union.

That idea collapsed with the Communist regime, but Chevron did enter into a joint venture with Kazakhstan to develop the Tengiz oil field in 1993 -- an onshore project in western Kazakhstan that first vaulted this newly independent nation into Westerners' view. Even before that deal was completed, Mr. Giffen negotiated a fee from the company for what Chevron officials said was his early role in the Tengiz deal.

Under the terms of the agreement with Chevron, Mr. Giffen would no longer perform services for the company but would receive a small percentage per barrel of all of Chevron's oil pumped from the field for about a decade. Neither Mr. Giffen's lawyers nor the company would discuss details.

Today, signs abound in Almaty of Kazakhstan's opening to the outside world. Chevron, ExxonMobil and other companies support an American Little League here, managed by one of Mr. Giffen's chief lieutenants. Grocery store clerks swipe Visa cards at crowded checkout lines. The only time that an American executive is likely to see a yurt, the traditional banner-draped nomadic tent, is on a visit to the gleaming Hyatt Regency hotel, where one has been erected over the circular atrium bar.

It is a scene that gives great satisfaction to Mr. Giffen, who recalled forging his alliance with Mr. Nazarbayev by pledging to place his talents at Kazakhstan's disposal.

''I said, 'Let's go, boss; let's build a country,' '' Mr. Giffen said.

An article last Sunday about James H. Giffen, an American businessman who advises the government of Kazakhstan, misstated the name of the mountain range that dominates the Kazakh city of Almaty. It is the Zailiski Alatau, not the Altai.

Original source: