In Kazakhstan, children with special educational needs and disabilities are kept out of sight and out of mind.

In Kazakhstan, children with special educational needs and disabilities are kept out of sight and out of mind.

For most Kazakh citizens, children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) exist in a parallel universe, a non–existent world where “normal” people will never have to tread – or at least don’t think they ever will, even today. A quarter century after the demise of the USSR, many people who were brought up and educated in the Soviet period are still naively convinced that in Kazakhstan there are no people with either physical or learning disabilities.

You never see these people anywhere. The infrastructure of Kazakhstan’s towns and villages makes no allowance for the needs of their disabled residents. Wheelchair users are not only unable to access public transport independently – they can’t even leave their homes. Even the country’s large cities, such as the capital Astana, Almaty and Shymkent have only recently begun to think about the needs of people with disabilities, and even then are making slow progress. The relevant laws and declarations still only exist on paper.

In Kazakhstan, the only people who need SEND children are their families. The state’s child protection services lack any concept of unconditional love towards them. Parents worry about their children’s future: what will happen to them when they, their main guardians, are gone and their care will be in the hands of the state? Parents, for their part, do everything they can to ensure that their children are educated and socialised. Most of the organisations and rehabilitation and therapeutic services for people with learning disabilities have been set up by parents themselves, often with active support from people with other disabilities.

In children’s facilities, secondary schools and universities you will never see a child or adult with anything other than typical development. Visually impaired or blind children, hearing impaired or deaf children, children with autism, cerebral palsy or Down’s syndrome – these are all beyond the comprehension of Kazakh society.

In practice, all these “special” children go to “special” boarding schools and for most of them, their future choices are limited to a small range of options dictated by the state – shoemaking, key cutting and minor repairs. And that’s if they’re lucky.

For a considerable number of SEND children, the world stops at the door of their flat and their social circle consists of their parents (often just their mother) and other family members. Some parents of such children don’t even go outside with them, fearing their child may behave inappropriately in public – and people’s reaction to them.

Down’s syndrome: the children who won’t survive without their parents

One typical example is children with Down’s syndrome, who are accepted by other children, but not by adults. What is the incidence of this condition in Kazakhstan? There are no official figures on the subject, but according to the World Health Organisation it is a fairly common condition: one in 700 children are born with the syndrome across the globe.

The mother of Naziya, 10, tells me how her daughter tried to play outside with the other kids, but that their parents wouldn’t let them play with this “strange” child. And according to her mother, a worker at Naziya’s nursery school deliberately burned her daughter’s arm with an iron, after which she became shy, nervous and aggressive. Nadiya’s mother says that children with Down’s syndrome become submissive to people they are scared of. She had to take her child away from nursery school and was also afraid to send her to school.

“She was just beginning to come out of herself, starting to smile”, her mother tells me. “Now she won’t leave our flat, and her social worker and teacher [paid for by the state] visit her at home. Like most children with this syndrome, she has bad eyesight and a weak heart.”

Naziya’s mother herself has a hearing impairment, and has had a hard life. Her own mother handed her over to her grandmother to bring her up – abandoned her, in other words. She was embarrassed about her deafness, and didn’t even finish secondary school. She moved to Almaty in pursuit of happiness and had her daughter when she was 43, but her husband didn’t give her any support and they divorced, so now she is bringing Naziya up on her own.

She also tells me that she wants to have a long life, so that she can look after her daughter, and says that having Naziya changed her life. She gained confidence in herself, became strong and happy and was no longer lonely – all thanks to Naziya. But the question of her daughter’s future floors her completely. Naziya can’t live independently. Her speech is not good, and she can’t fit into either a mainstream school or a special boarding school. So her mother hopes to be with her throughout her life, and her main wishes are strength, a roof over her head and some financial stability.

“We have to try to live as long as possible”

This phrase was repeated in every interview I had with parents of learning–disabled children. Their worst fear, after all, is what will happen to their “special” child after their death.

The mother of Sasha, 23, who has severe learning disabilities and is still, cognitively speaking, a child, says that her son’s brain died when he was less than a year old. Sasha can barely speak and he has spent many years in a city flat with his mother and grandmother; his future is very uncertain. He can neither read nor write, nor cope with simple activities of daily life. He also has a number of chronic physical conditions, including a heart defect.

Sasha’s mother believes that there will be only one route for Sasha after her death – into a care home for children with disabilities, where he won’t survive – they’ll just put him on psychotropic drugs. Her fears are well founded. Prosecutorial inspections have revealed a huge number of infringements of the rights and interests of people with disabilities, including corruption and theft and embezzlement from residents by care facilities’ management.

She also dreams of living a long life: “And what if I live to be a hundred?” she muses.

The most surprising thing is that the parents of these children don’t complain and don’t ask for support from the state. They haven’t become inured to the situation and they don’t see themselves as victims. Rather than relying on help from the state, they find ways of socialising and developing their children themselves. And the fact is that for an SEND child to be accepted by a public rehabilitation and development centre, they need to undergo an assessment by a state clinic and get a referral.

All the parents I spoke to about their children’s future told me that this was a big problem. But at the same time they all talked about how the birth of their “special” child had changed their outlook on life. They had begun to appreciate and love life as never before – to reassess their system of values. They all talked about the happiness this little person had brought them. This unexpectedly positive message simply amazed me.

The parents of 11–year old Islam, who has an autistic spectrum disorder (ASD), blame their son’s condition on the doctors who gave him a diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough (DTaP) vaccination despite his having a cold at the time. They lived and worked in the UK at the time, where the quality of medical treatment and early diagnosis of autism seemed better than in the countries of the former USSR. They discovered, however, that British doctors don’t believe in the theory that vaccination can be one of the reasons for ASD. The subject of vaccinations for newborn babies is, however, a sensitive one, and there is no direct proof of a link between DTaP vaccination and autism.

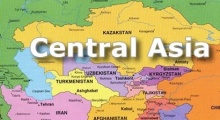

Back in Kazakhstan, Islam’s parents set up an organisation to help families living with ASD in Central Asia. Kazakhstan is the only country in the region where the issue is openly discussed, and there are organisations that provide financial, psychological, educational and other support to families with a child with autism. There are no such organisations in either Uzbekistan or Tajikistan: in these countries parents are on their own.

The subjects of autism and Down’s syndrome are hushed up in Central Asia, regarded as shameful. Where Down’s syndrome is concerned, the old Soviet practice of advising a new mother to reject her “sick” child and leave it behind in the maternity hospital is still in force. When this happens, the children are sent to specialised children’s homes where their care is strictly formal. As for children with ASD, they need particular love and attention, as their socialisation depends on their psychological well–being and the fulfilment of their needs. There has recently been a series of scandalous stories around children’s homes, although the idea of a move towards a foster care system is controversial.

One in a hundred inhabitants of our planet is on the autistic spectrum. In Kazakhstan, figures on the subject vary, because the issue falls within the remit of two different ministries. A specialist tells me that the two ministries have different agendas: for the Ministry of Education, the important thing is to have a timely medical assessment of children in mainstream schools, while the Ministry of Health only receives information about ASD children if their parents ask for help.

The official ASD figures and the unofficial data differ widely. According to the official figures, in 2003 there were only 77 children with autism, whereas in 2017 that number had ballooned to 3820, and the numbers have been rising year on year.

Inclusive education: the latest trend in Kazakhstan

Meanwhile, Kazakhstan’s government is attempting to introduce inclusive education into its mainstream secondary schools, although its attempts feel more like empty promises: there is as yet no concrete basis for their implementation. And the foreign term “inclusive” is only just entering the Kazakh lexicon.

The government’s educational development plan for 2011–2020 includes a stipulation for 70% of schools to become inclusive by 2020. But in fact, neither the school buildings, nor the teaching staff themselves are ready for the change. Neither older teachers whose careers started under the Soviet system, nor new graduates of pedagogical universities, have any idea of what the new approach will entail. Schools have as yet no specially trained tutors for students with learning difficulties, and the necessary infrastructure for those with a physical impairment (lifts, ramps, specialised desks and other items of furniture, as well as equipment and classrooms themselves) is not ready either.

The plan can only be implemented in Kazakhstan’s large cities at best. But the provinces are still living in the past anyway. Many village schools still have outdoor toilets, with no hot water.

The plan’s critics are already lending their professional weight to the matter of why it is still too early to introduce inclusive education to Kazakhstan. According to Aida Dadybayeva, who heads Almaty’s Centre for Speech and Language Therapy, the idea is still shapeless and in an embryonic state. She believes that inclusivity can’t just be copied from Europe and the USA, because it’s essential to take the peculiar qualities of Kazakhstan’s special education into account, not to mention the peculiar qualities of the Kazakh mentality.

It will also be necessary to train tutors in the specifics of SEND education before they take a child into a classful of typically developing youngsters. Dadybayeva feels that an inclusive class should have 15–18 students, not the usual 30. She also believes that there are many more problems still to be solved in legal, professional and material terms. There are also children whose specific issues will not allow them to become part of an inclusive class.

Dadybayeva has identified one more thing that will cause problems with inclusivity. The Kazakh public isn’t yet ready to accept these children: “We don‘t do acceptance in our society: even adults point their fingers at them and say ‘what a rude child’, without understanding the reasons for their behaviour.”

Irina Smirnova, a member of Kazakhstan’s Majilis (lower house of parliament) and former biology teacher and head teacher, also feels that it’s still early to introduce an inclusive education system. The reasons are obvious. In the first place, school buildings in Kazakhstan, whether from the Soviet period or of more recent construction, have nothing to help SEND pupils access their specific needs. Mainstream schools have no lifts for less mobile children; there have never been any adaptations for blind students (no Braille materials) or sign language provision for deaf ones.

“When parents started bringing their SEND children for inclusive education, all this seemed pretty complicated to us old–school teachers. There was a lot we didn’t know and we were even scared of these new trends,” Smirnova says. “And as for children with full–blown autism or on the autistic spectrum [ASD], we had no idea what it was all about. So when an apparently normal child suddenly burst into tears or showed signs of aggression, we didn’t know how to react. We had no special training for this. And I can’t say that older teachers have learned to adapt their methods either. Even young teachers just out of university have little training in how to behave with these children.”

Kazakhstan’s press publishes general information about inclusion and popular–science articles on the subject of inclusion on educational websites. But the parents of children with learning disabilities are still isolated – other parents don’t want to know about their problems. So the central task facing both education officials and public campaigners is to educate Kazakhstanis in the acceptance of people who are different from them.

This task is much more difficult than introducing an inclusive education system. Stigmatisation of children with learning disabilities is still widespread in Kazakhstan. And acceptance is only talked about in relation to ethnic and religious tolerance, as though Kazakh society is homogeneous in every other way.

The most obvious example of a lack of acceptance of children with disabilities is a statement made five years ago by Dariga Nazarbayeva, daughter of Kazakhstan’s president and an MP herself. At a parliamentary committee meeting, she called the wrath of the internet community down on her head by referring to these children as “freaks”.

As I was putting this article together, preparations were going on for a big event in Astana – Constitution Day. Children were rehearsing a concert for the president and the Astana Mayor’s office, and some of them were wheelchair users. These children and their parents were really happy about this opportunity to be like everybody. But at the last moment, the disabled children were banned from appearing in front of the president and parliamentary leaders.

One mother wrote on her Facebook page: “Our children were hidden away in the university building. While other children and adults performed, we sat in the dining hall and awaited our turn. But we weren’t called, the only reason being that the president and parliament don’t like seeing wheelchair users.”

OpenDemocracy, 27 September 2018