As Internet penetration grows in the country, so do the government’s attempts to monitor, control and repress dissenting voices.

As Internet penetration grows in the country, so do the government’s attempts to monitor, control and repress dissenting voices.

As Internet penetration grows in the country, so do the government’s attempts to monitor, control and repress dissenting voices.

As of April this year, internet users in Kazakhstan will no longer be able to leave anonymous comments online. In late December 2017, President Nursultan Nazarbayev signed a law obliging websites to register every internet user who wishes to leave a comment, either by SMS verification or digital signature. Websites who fail to abide by the new rules could face fines of up to $750. Kazakhstan’s Minister of Information and Communications Dauren Abayev said that everyone “must be responsible for what they want to say.” “In cases of incitement to interethnic discord or calls for unconstitutional actions, I think it should be possible for law enforcement agencies to track down commenters,” Abayev told the press before the bill was passed.

In response to the new law, several independent media outlets including regional newspaper Uralsk Week and news portal Ratel have completely removed the option of leaving a comment from their websites. Lukpan Akhmedyarov, editor-in-chief of Uralsk Week, said that he is against the new rule and decided to remove the comment section from the newspaper's website.

“In principle, I am against this new law, because it violates our right to free speech. We decided not to play by the government’s rules and removed the comment section from our website instead. Now we have observed that traffic to our website has not decreased and our readers have started commenting on our news directly on social media, like Facebook,” Akhmedyarov told me via telephone.

The latest legislative measure is only part of a set of repressive policies adopted by the government to tighten control over the internet in recent years. In July 2017, new government regulations granted the National Security Committee, the country's intelligence agency, authority over the centralised telecommunications network, Kazakhstan's single gateway to internet access.

Over the years, people in Kazakhstan have grown used to taking their social and political commentaries to social media, and despite the government’s efforts, this practice may prove hard to eradicate

In the aftermath of the December 2011 Zhanaozen violence that left at least 15 people dead as a result of police forces opening fire against unarmed protesters, internet access was curtailed. In the weeks following, Kazakhstan's parliament passed amendments to the National Security law, which allowed the government to shut down internet access and mobile connection during mass riots or anti-terrorist operations held in the country. The amendments also forced internet service providers and mobile operators to block their services when an official order is issued.

The new version of the law allows the General Prosecutor to request an internet shutdown without a court order in the event of calls to “participate in unauthorised public gatherings, calls for terrorism, extremism and mass riots.” Since 2014, the Prosecutor’s powers were extended to websites that contain “illegal material.” In February 2015, during clashes between Tajiks and Kazakhs in South Kazakhstan, broadband and mobile connections became inaccessible.

A court order issued on 13 March this year applied the “extremist” label to the Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan (DVK), an opposition movement set up in 2001 and led from exile by Mukhtar Ablyazov, a former minister and banker. The court ruled that DVK “calls for forcible change of Kazakhstan’s constitutional order” and is therefore classified as extremist. Any show of support to DVK, including on social media, could land individual internet users in jail for up to two years for “participation in the activities of a banned public or religious association”.

As a result, on 15 March, an alleged DVK supporter in Almaty was placed under house arrest. The following day, police interrogated Askar Shaigumarov, a video blogger from the city of Uralsk, regarding his “positive endorsement” of DVK. Over the years, people in Kazakhstan have grown used to taking their social and political commentaries to social media, and despite the government’s efforts, this practice may prove hard to eradicate.

Censorship in the name of “national security”

President Nursultan Nazarbayev has ruled Kazakhstan since its independence after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. No elections in Kazakhstan have been recognised as free and fair by international observers. In 2010, Parliament passed a bill that granted Nazarbayev and his family immunity from prosecution by declaring him Leader of the Nation, and criminalising the defamation of his figure in the media.

Out of 18m people living in Kazakhstan, over 13m people are internet users according to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). As of 2017, the internet penetration rate in Kazakhstan is relatively high among Central Asian republics at 76.8%, according to Freedom House. Kazakhtelecom, the 51% state-owned national internet service provider, has increased its domination of the domestic telecoms market in recent years. In July 2009, Nazarbayev signed a bill that recognised internet resources, including websites, blogs and social media, as mass media, thus bringing them under the regulations of the mass media law. The new legal configuration triggered the banning of LiveJournal and WordPress, popular blogging platforms. Analysts saw the new measure as a blow to Nazarbayev’s son-in-law Rakhat Aliyev, who had used LiveJournal to publish posts against the president.

Starting from January 2015, “spreading rumours” in Kazakhstan can land you in prison for up to ten years. Under Article 242-1 of the Criminal Code approved by Nazarbayev in July 2014, the “deliberate propagation of false information” both in press and social media is a criminal offence. Together with Article 174 (“inciting national, ethnic and religious discord”), the Criminal Code has established a broad and vague framework for silencing potential critics of the regime.

In 2016, social media user Sanat Dosov was charged under Article 174 and sentenced to three years in jail for insulting Russian President Vladimir Putin on a post on his Facebook page. In a similar case, political activists Serikzhan Mambetalin and Yermek Narymbayev were convicted of “inciting national discord” on 22 January 2016 for their Facebook activity. Both activists were barred from engaging in civic activities for five years. Narymbayev later fled the country and is seeking political asylum in Ukraine.

State propaganda portrays Kazakhstan as a haven of interethnic peace and stability and this view cannot be contradicted by online users

New legislative measures and recurring court cases against social media activists have induced more and more internet users to self-censor their online presence for fear of reprisal. Since January 2016, local authorities have also demanded that all internet users install a National Security Certificate on all devices. This measure has allowed the government to increase its surveillance capabilities. Internet activist Dmitriy Schelokov said that he is aware of government surveillance.

“I'm not particularly affected by internet censorship. I use VPNs to access blocked sites. It's sad, however, that I have to be cautious while posting and chatting online, because I am sure I can be tracked by law enforcement agencies. Luckily, there are now secure messaging apps like Telegram that offer end-to-end encryption and I can text or call with confidence that the government cannot track my communications,” the internet activist told me via Telegram.

Screenshot of a failed attempt to access petition platform Avaaz.org from the territory of Kazakhstan (March 2018).Apart from blocking opposition websites and blogging platforms, the government has also impaired access to internet tools used to circumvent censorship. A number of web anonymisers, including stupidcensorship.com, proxify.com and ninjacloak.com have been blocked in Kazakhstan since 2011. Independent media outlet Ratel.kz is periodically blocked within Kazakhstan, especially after the publication of stories that uncover high-profile corruption cases.

The popular global petition platform Avaaz has also been blocked in Kazakhstan since 2014, after activists initiated a petition calling for Nazarbayev’s impeachment due to his inability to improve living conditions in the country. Importantly, the website was blocked on 11 February 2014, the day of a Central Bank-mandated 19% devaluation of the national currency, which triggered widespread public discontent. Change.org, another global petition platform, has been inaccessible since 2016 because it hosted a petition calling for the dismissal of then-prime minister Karim Massimov, who now heads the National Security Committee.

“Kazakhstan is a land of peace and stability”

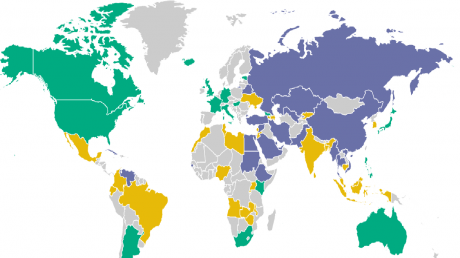

State propaganda portrays Kazakhstan as a haven of interethnic peace and stability and this view cannot be contradicted by online users. According to a Google Transparency report, between January-June 2017, Google received a substantial number of requests from the Kazakh authorities to remove content, the vast majority of which were for “national security” reasons. As pictured in the chart, government requests related to National Security reached an all-time high since 2009. The report also mentions that Kazakhstan's government requested Google to remove “the YouTube channel for a TV channel supportive of the opposition.” Google did not comply with the request.

Google Transparency Report on Kazakhstan. Website screenshot (March 2018).Domestically, over 9,000 websites have been blocked for “extremism and terrorism” content according to minister Abayev. Several world-renowned video and photo hosting platforms including Vimeo, Flickr and Tumblr are routinely blocked in Kazakhstan by court order for “extremist and pornographic content.” In 2014, Kyrgyzstan’s independent media outlet Kloop.kg, Russian independent news website Meduza, and British tabloid The Daily Mail were all blocked for publishing material about Kazakh children allegedly joining ISIS. Authorities also practise selective filtering of online content. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s individual URLs containing news articles on Kazakh militants joining ISIS were selectively blocked in 2015.

Kazakhstan's authorities have adopted increasingly restrictive legislative measures and opened criminal cases against social media users to silence critical voice

Network connections have become spotty throughout the country and in selected regions for disparate reasons, such as during mass protests, ethnic conflicts and when Ablyazov runs his opposition livestreams on Facebook and Instagram. Every year, around the anniversary of the Zhanaozen massacre, when activists plan to organise demonstrations, internet users experience problems using WhatsApp, Instagram and other social networking sites.

In April and May 2016, during mass protests across the country against a proposed land reform, internet users had difficulties accessing Facebook and Google. Since access to internet is also curtailed on ordinary days, activists have speculated that law enforcement agencies have been testing their ability to shut down the whole internet, should it become necessary.

Kazakhstan's authorities have adopted increasingly restrictive legislative measures and opened criminal cases against social media users to silence critical voices and induce self-censorship online.

As the importance of online media and communication have grown significantly over the last several years in Kazakhstan, including for the expression of dissenting voices, so have government attempts to tighten control.

Open Democracy, 26 March 2018