Kazakhstan — Central Asia’s most stable state — is waking up to the fact that Islamic extremism has planted its roots and is here to stay.

Kazakhstan — Central Asia’s most stable state — is waking up to the fact that Islamic extremism has planted its roots and is here to stay.

AKTOBE, Kazakhstan — A quiet Sunday morning came to an end on June 5, 2016, as 27-year-old Dmitry Tanatarov led a group of 25 young men in what would become Kazakhstan’s largest terrorist attack ever.

The group, whose ages ranged from 17 to 28, moved quickly down a dusty street in downtown Aktobe, an oil city in northwestern Kazakhstan, and seized weapons from two gun shops to begin a series of attacks across the city. After securing the weapons, the men would go on to hijack a bus, assault a nearby national guard base, engage in numerous shootouts with police, and attack a police checkpoint before going underground. By June 11 — six days after the attack began — the remaining attackers had been found in hiding and arrested or killed in firefights with the security services. In the end, the outbreak of homegrown terrorism claimed 25 lives — including 18 of the attackers — and shook the Central Asian country to its core.

According to officials, Tanatarov — who died from injuries after a shootout — and several of the other attackers attempted to go to Syria about a year before but were unable to make the journey. Resigned to Kazakhstan, the men decided to form their own atomized cell and attack members of the country’s security services.

The next month, on July 18, the country was hit by another attack. Ruslan Kulekbayev, a gunman who police later said was radicalized while serving a prison sentence, opened fire on a police station in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city and financial center, killing eight police officers and two civilians before being arrested by the authorities after a shootout and pursuit across the city. Neither of the attacks had direct connections to extremist groups from abroad — or with one another — but officials say extremist teachings found online, including those from the Islamic State, inspired both incidents.

For the Kazakh government, the episodes were a crude wake-up call that extremism had firmly planted its roots in the country and was growing. Kazakhstan, a country of 18 million whose population is 70 percent Muslim, has remained largely untouched by the type of extremism that has affected most of its Central Asian neighbors. The country’s secular government and autocratic president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, have branded Kazakhstan as a beacon of stability in an otherwise troubled region and used this reputation to court investment and credibility on the world stage. But the attack in Aktobe, a major center for the country’s vital oil industry about 60 miles from the Russian border, exposed cracks in that facade.

Now, more than a year later, the government has modified its counterterrorism strategy — and how it deals with radicalization more broadly — in hopes of cutting off the problem before it spreads further. But the government is left playing catch up, instituting measures that many experts contend should have been implemented years ago and others that could inflame the problem of radicalization even more in the future.

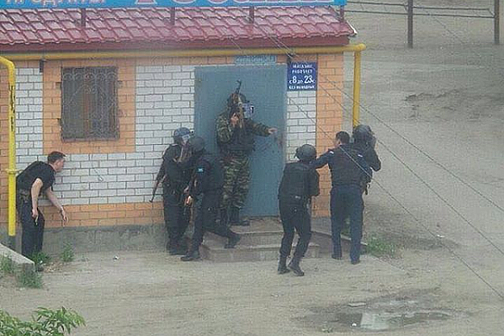

Kazakh security forces conduct operations to track down the assailants from the June 5, 2016 attack in Aktobe. (Image via VKontakte) Right: An image circulated on social media of a police car outside the "Pantera" gun shop in Aktobe that was raided by attackers on June 5, 2016. The image shows the bodies of two attackers on the ground.

The specter of Islamic extremism has loomed over Central Asia since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. After 70 years of state-imposed atheism, the region found itself once again connected to the wider Islamic world, sparking a religious revival for many Central Asians. But the lack of continuity also meant that Islamic literacy in the region was low. The new connections brought more extreme interpretations of the faith from abroad, such as Salafism from the Middle East and the North Caucasus. Despite the nominal end of official atheism, independent Central Asia was still ruled by many of the same Soviet-era strongmen and remained secular. With other political avenues restricted, more extreme versions of Islam quickly became an outlet for followers chaffing against the region’s authoritarian leaders.

Over the decades, numerous terrorist attacks took place — with Uzbekistan being the hardest hit — but the region’s heavy-handed security services managed to crack down on most of Central Asia’s extremist groups: arresting and killing many while driving others abroad. In exile, groups likes the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which aimed to overthrow the Uzbek government, took root in Afghanistan and later Pakistan and joined forces with the Taliban. Other Central Asian extremists followed suit and moved south where they integrated into al Qaeda-linked groups with global ambitions.

This has led to fears that the Islamic State will start to turn its attention toward Central Asia as it continues to lose ground in Iraq and Syria.

This evolution accelerated following the outbreak of civil war in Syria in 2011 and again in 2014 after the declaration of a caliphate by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. The Soufan Group, a security consultancy, estimates that 2,000 Central Asian foreign fighters have joined the Islamic State and other extremist groups in Iraq and Syria — with about 300 from Kazakhstan. Central Asians have also figured prominently in several international attacks claimed by the Islamic State and al Qaeda, including the Istanbul airport assault, the Stockholm truck attack, and the St. Petersburg metro bombing. This has led to fears that the Islamic State will start to turn its attention toward Central Asia as it continues to lose ground in Iraq and Syria.

Kazakhstan remained the most sheltered from this trend over the years. But as illustrated by the attacks in Aktobe and Almaty, the country faces a growing threat from homegrown extremists, rather than a global extremist group. While Kazakhstan has had some terrorist attacks in the past — including a spate of incidents in 2011 and 2012 — the summer of 2016 increased the urgency of how Astana views the problem of extremism. Following the attacks, the government created the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Civil Society, tasked with engaging the religious community and crafting policy aimed at preventing extremism. The new ministry’s portfolio consists mostly of youth outreach, encouraging Islamic literacy, and what it calls “informational propaganda” — that is, promoting what it deems to be the correct interpretation of Islam.

While the authorities are formulating a response, they appear to be learning the wrong lessons from the recent wave of extremism. The Kazakh government said those involved in the Aktobe attack were “followers of radical, nontraditional religious movements,” which is official parlance for more conservative forms of Islam, and said the attackers were influenced by forces from abroad. While seemingly true, the focus outside the country overlooks the role that domestic factors played. Instead, state rhetoric has taken to dividing Kazakhstan’s Muslims between those it deems “traditional” — followers of the more moderate form of Sunni Islam practiced in the region — and “nontraditional,” followers of more conservative strains of the faith that have spread in the country over the last 25 years. This distinction has led to a fixation from the government on Islamic garments and other outward signs of religious observance.

“We see these people wearing this clothing as uncharacteristic of Kazakhstan and these people wearing all black or long beards as influenced by values from abroad,” Berik Aryn, Kazakhstan’s vice minister of religious affairs and civil society, told Foreign Policy during an interview in Astana.

Similar comments have been made by Nazarbayev himself. In a meeting with the country’s religious leaders on April 19, the president derided conservative religious garb as “incompatible” with the country’s traditions, saying that “Kazakhs wear black garments only for funerals” and that a legal ban on such attire might be necessary. Such a law is reportedly in the works and could be introduced into Kazakhstan’s rubber-stamp parliament later this year. Should the measure be adopted, it would follow similar controversial legislation passed in Belgium and France. Moreover, the issue raises complex questions about the role of Islam in Kazakhstan’s young national identity that are unlikely to be discussed openly given the country’s restrictive information space.

This approach could also easily backfire and potentially increase radicalization in the country. “It’s very dangerous to only pay attention to the outside displays of someone’s faith,” said Serik Beissembayev, a researcher at the Institute of World Economics and Politics, a think tank in Astana. “It’s the inner beliefs that drive them to extremism.”

“This puts the government in the middle of a wider struggle taking place around the globe between true believers and so-called infidels,” Beissembayev said.

Beissembayev, who has spent years researching Islamic radicalization in Kazakhstan and interviewing convicted extremists in prisons, says the movement has strong social roots and is bred out of poverty, a general lack of prospects, and anger over corruption. A report released this year by Transparency International echoed these findings, noting that extremist groups — from Nigeria to Indonesia — specifically targeted potential recruits disillusioned over state corruption. Moreover, Beissembayev adds, the Kazakh government’s focus on Islamic garb provides material to further radicalize Muslims who already see the secular state as encroaching upon the rights of the pious.“This puts the government in the middle of a wider struggle taking place around the globe between true believers and so-called infidels,” Beissembayev said.

In addition to moving to ban certain conservative forms of dress and promoting state-approved Islam, Kazakhstan’s influential security services have elected for a heavy-handed approach to counterterrorism. The Kazakh security services already have vast surveillance powers but have used the 2016 terrorist attacks to lobby for strengthening the country’s Soviet-inherited internal migration laws. The new measures require any citizen to re-register with the authorities if they spend more than a month in a new city. For Dosym Satpayev, the director of the Almaty-based Risk Assessment Group, a political consultancy, this reaction is illustrative of the counterproductive response taken by the security services toward fighting extremism. Satpayev, who was a member of a parliamentary group formed after the attacks designed to craft legislation aimed at fighting terrorism and extremism, says the security services won the conversation when it came to how to respond, pushing for even broader powers. Such an approach, he argues, will do little to push back against the spread of extremism in the country as long as corruption and distrust of the state authorities remain widespread.

“Against [extremist] ideologies that are very effectively recruiting people, we need to have a strong counternarrative from the government to combat it,” Satpayev said. “But the government doesn’t really have such a narrative to respond with.”

Satpayev maintains that government authorities closed their eyes to the prospect of Islamic extremism spreading in Kazakhstan. While the country’s neighbors struggled with episodes of terrorism, Astana remained confident that its moderate population and higher living standards would insulate it from similar problems. During meetings in the late 1990s, Satpayev recalls being accused of spreading hysteria by officials for raising the alarm of Islamic extremism in the country. “They used to say to me, ‘We’re not Uzbekistan. We’re an island of stability,’” Satpayev said.

The Aktobe and Almaty attacks seem to have finally changed this perception, but the window of opportunity may have since passed.

“It’s too late now,” Satpayev said. “It’s already spread, and it’s not going away.”

Tanatarov, whom officials describe as the ringleader of the Aktobe attack, grew up poor in that very city. Orphaned at a young age and raised by his grandmother and older brother, Tanatarov struggled in school and had a reputation of being somewhat of an outcast. According to a childhood friend who spoke to FP on the condition of anonymity, Tanatarov would drink and smoke, loved bodybuilding, and wanted to be a career military officer, but his lack of means and difficult upbringing were a constant chip on his shoulder. After a year of military service in 2008, he was denied entry into the career-track program and, according to his friend, bounced around between odd jobs and struggled to make ends meet, even sleeping in his car for a period of time. About a year later, Tanatarov converted to Islam. He then worked in construction around Aktobe for the next several years, stopped drinking, and slowly drifted away from his friends.

Few details remain about how exactly Tanatarov came to take part in the June 2016 attack, but Kazakh officials say he joined a Salafi group and decided to recruit members for his extremist cell. Balgabek Mirzayev, a theologist who works for the Kazakh government and who interviewed the surviving Aktobe attackers after their arrest, told FP that a core group of the men knew each other for some time before the attack and would listen to lectures together of ultraconservative clerics from the Caucasus and translated videos of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State. According to the official indictment, Tanatarov invited 44 people to an apartment the night before the attack on the pretext of celebrating the birth of a newborn child but used the occasion to recruit members for the cell he was founding. Tanatarov and a small group played a video from the Islamic State and then made an appeal to attack members of Kazakh law enforcement. Twenty-two men left, not wishing to participate, while the remaining men launched the attack the next morning.

While some questions remain about the government’s official narrative, many of the other attackers share similar backgrounds as Tanatarov: living lives of poverty, working in the gray economy, and some even serving time in prison.

Aiman Umarova, an attorney based in Almaty who has worked on some of Kazakhstan’s most high-profile extremism cases, says similar portraits of poor, disaffected youth are common for many of those convicted of extremism in the country’s prison system. She remains a critic of the government’s approach to countering extremism, which she says has little focus on prevention and could be abused to crack down on activists and violate human rights.

“Islamic extremism and terrorism are serious problems that the government should fight,” Umarova said. “But my job is to make sure that the government doesn’t cheat in doing this.”

And with the government focused on arresting potential terrorists and locking them away, rather than trying to prevent the growth of a new generation of homegrown extremists, Umarova is worried about Kazakhstan’s future.

“All the conditions are here. This problem will only grow,” she said. “Our future will be violent extremism.”

Reid Standish reported from Kazakhstan on a fellowship with the International Reporting Project (IRP).

Reid Standish is associate editor, digital, at Foreign Policy. Reid writes on Russia, Ukraine, and Central Asia and is the newsroom’s digital point person. He has lived in and reported from Finland, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine, where he covered everything from Santa Claus to drug trafficking. A native of British Columbia, he holds a B.A. in international studies from Simon Fraser University and an M.A. from the University of Glasgow. (@reidstan)

ForeignPolicy.com, 01.08.2017