A cold drizzle fell on Istanbul on the morning of Dec. 10, 2014, as Abdullah Bukhari made his way to teach his students at a madrasa nestled amid apartment blocks and hardware stores in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood. A white prayer cap on his head, Bukhari made two crucial departures from his daily routine, according to one of his students: He told his bodyguard to stay at home and he didn't wear a bulletproof vest beneath his white ankle-length thobe.

A cold drizzle fell on Istanbul on the morning of Dec. 10, 2014, as Abdullah Bukhari made his way to teach his students at a madrasa nestled amid apartment blocks and hardware stores in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood. A white prayer cap on his head, Bukhari made two crucial departures from his daily routine, according to one of his students: He told his bodyguard to stay at home and he didn't wear a bulletproof vest beneath his white ankle-length thobe.

Two security cameras captured what happened: As Bukhari waited for someone to let him into the madrasa, he glanced to his left, settling for a moment on a clean-shaven man in a black winter cap and blue jeans, both hands tucked inside the pockets of a black jacket.

Three months earlier, the 38-year-old Bukhari had been told he had a price on his head. Two former Chechen rebels living in Istanbul had learned that the Uzbek imam was on a list of assassination targets — men wanted for their opposition to Islam Karimov, the president of Uzbekistan. Bukhari took the news well. "If Allah wants me dead, I will die," he told one of his students.

Bukhari looked away and the man in the black jacket got his chance, shoving the silencer of his 9 mm handgun between the imam's shoulder blades. A puff of smoke appeared. The gunman bolted down the street as Bukhari stumbled into the madrasa, dying shortly thereafter.

The long arm of Islam Karimov had caught up with him.

Since settling in Turkey 12 years earlier, Bukhari had opened five madrasas across Istanbul and developed a sizable following among the city's conservative Central Asian diaspora. His students numbered in the thousands, and included Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Chechens. Well-versed in Islamic law and theology, Bukhari used his sermons to extoll the virtues of jihad against Vladimir Putin in Chechnya and Bashar al-Assad in Syria. The imam welcomed the widows of Syrian rebels — Arabs and Central Asians alike — with open arms, offering them financial support and holding them up as an example for his students of sacrifice for jihad.

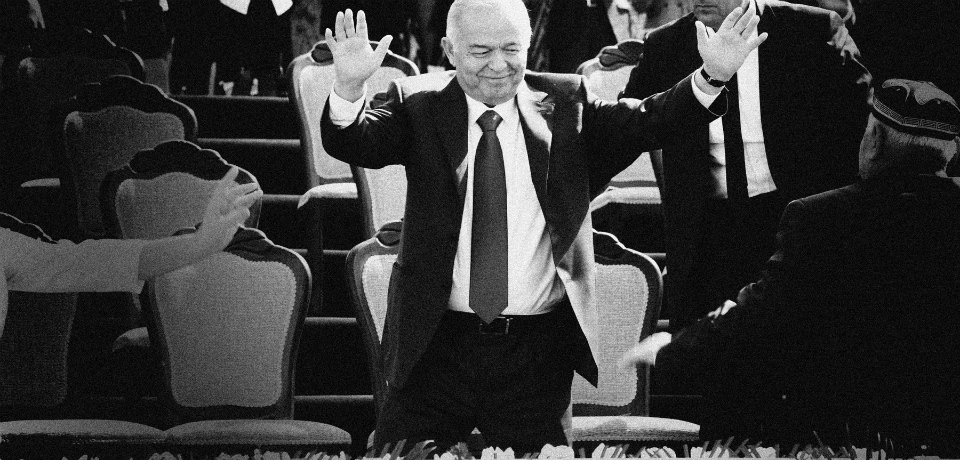

Bukhari also called for a movement to bring down Karimov. The 77-year-old former Communist Party boss is the only ruler Uzbekistan has known since gaining independence in 1991. Karimov has held onto power by imprisoning thousands of opponents, accusing many of being Islamic extremists. More recently, he has fingered his opponents as supporters of the Islamic State.

The Uzbek president's unrelenting pursuit of his critics has pushed peaceful opposition out of the country. For a man known to boil his critics alive, a usurper lurks around every corner. He has even imprisoned his globe-trotting, pop-singer princess of a daughter, Gulnara Karimova. On March 29, Karimov was re-elected to a fourth term, the second time he violated a constitutional two-term limit. Western observers criticized the election, in which the president won more than 90 percent of the vote, with a turnout of 91 percent.

Pious old Uzbek dissidents pray for the president's life to end, while others hone their skills as jihadis in conflicts across Asia and the Middle East. In the last decade, thousands have joined militant groups fighting in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and over the last few years, hundreds of battle-hardened Uzbeks have joined the Islamic State in its effort to establish a theocracy in Syria and Iraq. Many of the Uzbek jihadis have teamed up with Chechen rebels who hold Russian passports.

Bukhari fell somewhere in between. He expressed hope that the war in Syria would end with Islamist rule, but warned against infighting among the rebel factions and rarely mentioned the name of any particular group, either the Islamic State or the other al Qaeda affiliates.

As members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a regional political and security agreement, Moscow and Tashkent cooperate closely in tracking and countering militants. Member states readily extradite fugitives to other member countries and share intelligence on counterterrorism operations. Thousands of troops from Uzbekistan, Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan take part in annual "Peace Missions," retaking towns under mock terrorist occupation.

But Tashkent and Moscow have also used less official means of countering this threat — and silencing enemies of the state.

According to Istanbul police and investigators at the Turkish newspaper Yeni Safak, the man who killed Bukhari was Zelimkhan Makhtiev, an ethnic Chechen and Russian national who was part of a team of at least four being paid $250,000 and led by an Uzbek intelligence officer who goes by the code name Misha.

Last year, according to the Istanbul police, Misha ordered a Russian, Sobir Shukurov, to assemble a team to assassinate at least four Karimov critics — three Uzbeks and a sympathetic Kyrgyz imam. Makhtiev's inquiries about the dissidents raised enough suspicion among Turkish police that he was deported last fall, but he obtained a forged Ukrainian passport, and on Nov. 4, 2014, he and Shukurov returned to Istanbul, according to Turkish police. Makhtiev, Shukurov, and another Russian national, Eldar Aslan, are now in police custody. Police recovered documents in Russian and a short biography of each target, along with pictures and their locations.

The Turkish Interior Ministry forwarded inquiries about Bukhari's murder to the Foreign Ministry, which did not respond to a request for comment. The government of Uzbekistan refused repeated requests for comment for this article.

* * *

At a protest a month after Bukhari's assassination, thousands of demonstrators held up the imam's portrait alongside those of other assassinated dissidents from Uzbekistan and Chechnya. The crowd, composed mostly of Central Asian migrants, chanted, "Putin is a murderer, Karimov is a murderer!"

"Naturally, everyone is afraid," says Adem Cevik, the president of the Turkistan Union, an advocacy and support group for the 140,000 or so Central Asian migrants living in Istanbul. "These kinds of things happen all the time, not just in Turkey, but in Russia, in European countries, too. We are not afraid for our own lives, but for the future of our movement." Along with helping secure residence permits and providing medical care, the Turkistan Union lobbies for democratic reforms in Uzbekistan and other former Soviet countries.

"Karimov is behind all of this; he has the Russians take care of his problems," says Muhammad Salih, 66, head of Uzbekistan's outlawed Erk ("Freedom") Party, once the country's largest organized opposition. After Bukhari's assassination, Turkish police contacted Salih and his son, Timur, 34, to inform them that their names were included in the list of targets obtained from the assassin.

Salih, who ran unsuccessfully for president against Karimov in Uzbekistan's first post-Soviet presidential election, escaped an attempted assassination by Karimov's men in 1993. He then fled the country and lived on the run in Western Europe. In 2000, Salih barely escaped another assassination attempt in Norway. On several occasions, European diplomats have intervened to keep him from being extradited to Uzbekistan. Salih now lives in Istanbul with his family.

"This threat is more direct and more dangerous than ever before," Salih says. Bukhari's killers were caught with photos of Salih's son, and a satellite image of their Istanbul home. The usually media-friendly dissident has gone largely incommunicado, and now travels with a rotating team of plainclothes bodyguards. "They are professionals," he says. "Basically, they [the assassins] kill us, or we are going to kill them. There is no other choice."

Dilorom Iskhakova, 60, one of Uzbekistan's leading human rights activists, knows how Salih feels. She fled her country last fall after her daughter was arrested. She now lives in a small seaside town in Turkey, where she was placed by U.N. asylum officials. But Karimov's regime hasn't left her alone, she says. She receives threats by phone from a man speaking in broken Turkish: "Lots of swear words, and threats to kill us, to rape us, describing the house where we were living. Sometimes in five minutes there were up to eight calls, starting at 2 a.m."

* * *

According to Human Rights Watch, there are at least 10,000 political prisoners in Uzbekistan's jails today, the largest number in any post-Soviet country. Around 9,500 of them stand convicted of violating regulations on religion. Simply being caught reading religious texts in public — whether the Quran or the Bible — can lead to terrorism charges, according to Steve Swerdlow, a researcher with the group.

"These are essential politically motivated charges — in the Soviet sense — against an individual seen to be disloyal," Swerdlow says. Tashkent has denied requests for a visit by a U.N. special rapporteur on human rights since 2002, and the Red Cross stopped visiting prisoners in April 2013, calling the attempts "pointless."

Meanwhile, Karimov has pursued his critics across Europe and Asia. Scores have been extradited under pressure from Tashkent. In 2011, a court in Almaty, Kazakhstan, extradited 29 devout Uzbeks back to their country, despite appeals from human rights groups. The Uzbeks were quickly convicted and handed prison sentences of up to 15 years each.

In 1994, Kazakh authorities extradited Murod Juraev, a former Uzbek opposition parliament member, to Tashkent, where he was convicted of training militants. Juraev was sentenced to 12 years in prison, but his term has been extended four times, for offenses like "incorrectly peeling carrots." Regular beatings have taken a heavy toll on Juraev's health: He is missing most of his teeth, and has contracted tuberculosis, according to researchers at Human Rights Watch who interviewed his wife after she visited him in prison in October 2013.

Those who cannot be extradited are kidnapped, like Salih's brother, Muhammad Bekjanov, one of the world's longest-jailed journalists. In 1999, Bekjanov was kidnapped by Uzbek agents in Kiev, brought to a court in Tashkent, and promptly sentenced to 13 years in prison for "threatening the constitutional order." In 2012, he was handed a five-year extension for violating unspecified prison rules.

Despite decades of near-absolute rule by Karimov, Salih says he continues to hope for a peaceful political transition in Uzbekistan. The March 29 elections, he says, could have been an opportunity for Karimov to step aside and allow such a transition, but because Western powers like the United States continue to offer Tashkent military aid and see it as an ally in combating Islamic extremism, no such development has taken place.

"The United States does not look at the long term," says Salih. "In the long run, this will cause more harm to them." The alliance between Washington and Karimov, Uzbek opposition leaders fear, will lead more young people to join militant movements with global ambitions.

Karimov has demonstrated how far he is willing to go to hold on to power. In May 2005, in the eastern city of Andijan, soldiers carried out what at the time was one of the bloodiest government massacres in modern history. After a handful of armed locals freed 23 businessmen from prison, soldiers opened fire on thousands of demonstrators, killing around 600 civilians.

In the wake of the massacre, Western countries cut off the bulk of their funding for Karimov's military. Since 2003, the U.S. Congress has made direct military aid to Uzbekistan subject to annual reviews of its human rights record, standards that the Karimov regime failed to satisfy even before the Andijan massacre. But military-to-military cooperation, including training for the Uzbekistan military for counterterrorism and counternarcotics operations, continued, largely because Karimov had allowed American troops to operate out of the Karshi-Khanabad air base near the Afghanistan border.

After the Andijan massacre, the European Union halted military aid and slapped a visa ban on top Uzbekistan officials. The United States openly demanded that Tashkent allow an independent investigation into what happened at Andijan. Karimov responded by evicting U.S. troops from Uzbekistan.

But by 2011, when Pakistan shut down a major NATO supply route to Afghanistan, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was again meeting with Karimov in Tashkent. The Karshi-Khanabad base was still off-limits to American troops, but congressionally mandated restrictions on military funding were lifted. Tashkent received $5.3 million in U.S. military funding in 2012, $1.6 million in 2013, and $1.5 million in 2014.

This January, U.S. officials said Uzbekistan would receive 328 armored vehicles — worth, depending on their condition, up to $300 million dollars, making it one of the largest transfers of military aid to any former Soviet country in the region. The State Department has since defended the transfer, describing its relationship with Karimov as one of "strategic patience."

"We believe that we can continue to cooperate with Uzbekistan on common threats like terrorism and narcotics smuggling while also pressing the government of Uzbekistan to make progress on human rights," a State Department spokesperson told Foreign Policy in a statement late last month. "The government of Uzbekistan knows that our bilateral relationship cannot reach its full potential absent significant progress on human rights."

* * *

Islam Karimov's war on imams didn't begin with Abdullah Bukhari. One of the few challenges Karimov faced in 1991 — after he rigged the presidential election and jailed or expelled most of his political opponents — was a nascent Islamist movement in the Ferghana Valley, one of the most conservative parts of Central Asia, spilling across Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Islamists there, some with combat experience in the war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, had been unabashedly calling for sharia law. A group of Islamists even shouted down Karimov during a public debate in December 1991.

Karimov moved quickly, banning opposition parties like the Islamist Renaissance Party and jailing clerics, forcing prominent Islamists to flee to Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. The most violent among them formed the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and based themselves out of Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they found allies among the Taliban in the late 1990s.

While the IMU has been an active participant in combat in neighboring countries, Karimov's zero tolerance for any Islamist movement inside Uzbekistan has meant that the group has been largely absent from its home. In fact, the IMU's name is now more or less a misnomer — most of its members are thought to be Chechens and others from across Central Asia.

And yet Karimov has continued to use the group's reputation to pursue his political opponents: Salih and Iskhakova have repeatedly been charged with being leaders in the group.

Uzbekistan's campaign against an imaginary Islamist threat threatens to create a real underground Islamist movement, says Swerdlow. "The spectrum for Islamic thought and practice is narrowed to the point of strangling the religious community there, pushing it deeply underground and strengthening the position of organizations that are openly looking to overthrow the regime and even worse, committing terrorism," he says.

Since 2011, hundreds of Uzbeks have joined thousands of others fleeing political and economic marginalization in Central Asia and seeking to establish a new state in Syria. Some support the Islamic State, while others have pledged allegiance to independent, Chechen-led factions. Most make their way to Syria through Turkey, where a network of supporters provide them with temporary housing and transportation, and even find them spouses.

Bukhari, the imam assassinated in Istanbul in December, had amassed thousands of Uzbek, Tajik, and Chechen students, including some who were actively part of that jihadi support network. In his lectures, Bukhari cited dozens of classical Islamic sources to argue for jihad.

But the imam didn't support all jihadi movements equally. He occasionally criticized harsh tactics used by the Taliban and al Qaeda, and he walked a fine line when it came to the Islamic State: Last July, he produced a series of lectures refuting a much-heralded fatwa condemning the Islamic State by Yusuf al-Qaradawi, one of the world's most influential Sunni scholars. After citing evidence showing that Qaradawi chose the "idolatrous" idea of democracy over an Islamic caliphate, Bukhari systematically picked apart the fatwa's main contentions about whether or not a caliphate could be established in Syria, without ever concretely defending the Islamic State's attempt to do so.

* * *

Lately, Karimov has attempted to rebrand his decades-long war on dissent as a war on terror. On Dec. 10, 2014, the same day Bukhari was gunned down in Istanbul, Karimov hosted Vladimir Putin in Tashkent. The Russian president announced that Russia would write off $865 million in Uzbek debt. At a press conference after the meeting, Karimov praised Russia's leadership in regional security, and warned that "representatives of the Islamic State group have penetrated into Afghanistan from Iraq and Syria," and that they would enter Central Asia next.

Many say this will increase opposition to the dictator and create more jihadis, rather than fewer. "In a context where [recruitment for the Islamic State] is actually on the rise, the Uzbek government is doing exactly what it should not be doing," says Human Rights Watch's Swerdlow.

Uzbek human rights activist Dilorom Iskhakova agrees. She says she knows of at least one case that proves it: Ruhiddin, whose name has been changed to protect his family in Uzbekistan, was in his mid-30s when he was killed in action late last year in Syria. He had left Uzbekistan for Turkey more than 15 years ago, Iskhakova says, hoping to start a new life. Despite being a graduate of a prestigious Tashkent technical university, he could not make a living.

When an Uzbek police officer was killed near Ruhiddin's hometown in 2011, authorities detained hundreds of practicing Muslims from the area. "It's very easy to find these people," Iskhakova says, "because anyone going to a mosque, anyone praying, is on a list." Among those arrested were two of Ruhiddin's brothers, one of whom later died in prison, according to Iskhakova. In 2012, Kazakhstan extradited a suspect in the killing of the police officer to Tashkent. Ruhiddin, sensing he might be the next one to find himself in an Uzbek court, left for Syria.

"I don't know exactly what pushed him [to join the Islamic State], but I understand his condition," says Iskhakova. "[For] people who go [to Syria] and start fighting, for them it's a choice to die in prison in Uzbekistan, because they never let you out, or do something different with your life."

foreignpolicy.com